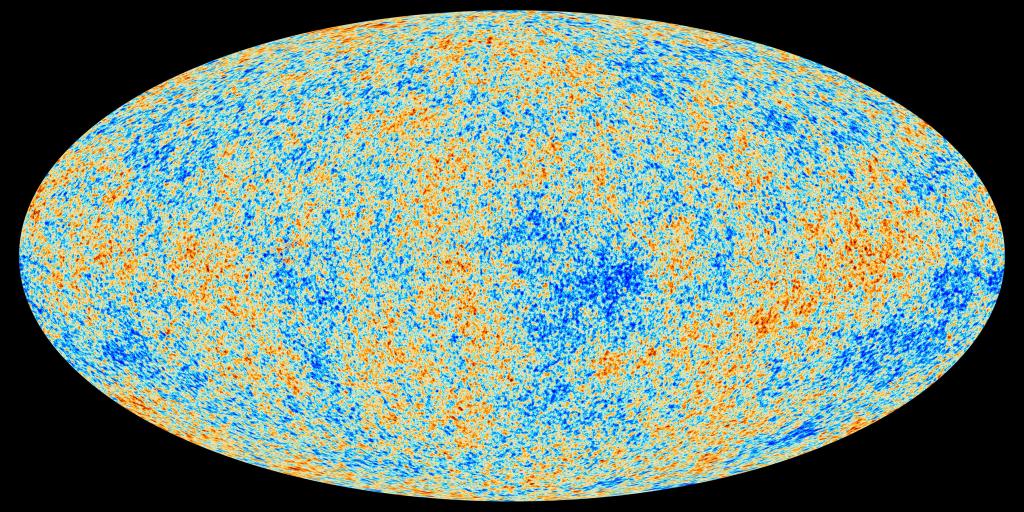

What if I told you that this was an actual image of the night sky?

Well…alright, I admit it’s more like a map.

Specifically, a map of the cosmic microwave background radiation, often known simply as the CMB.

This is the farthest we can see in the universe, and consequently, the farthest we can peer back in time. And it’s a critical springboard to answering some of the most fundamental questions about the universe.

But what the heck is the CMB?

This story begins in the mid-1960s, in Bell Telephone Laboratories — funded by none other than AT&T.

Physicists Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson were creating a radio receiver, and discovered the CMB completely by accident.

In fact, at first they were quite puzzled by a signal they were receiving. It looked like background noise, and it persisted no matter where they pointed their receiver.

They assumed the noise was coming from the telescope itself — perhaps from pigeon droppings. But even after cleaning out the droppings and (as the story goes) killing the pigeons, the signal remained.

As it turned out, this signal was coming from the entire sky.

But really, the story begins decades earlier, in 1939.

Astronomers studying the spectra of the interstellar medium noticed something strange.

It’s pretty common for the interstellar medium to be illuminated by nearby stars — that’s how we get a nebula, like the Orion Nebula above.

But some molecules were bathed in radiation from a source between 2 and 3 K (Kelvins).

People…the Kelvin temperature scale begins at 0, which is absolute zero, the theoretical lowest temperature possible. 2-3 K is at least a thousand Kelvins cooler than even the coolest stars. The source couldn’t possibly be nearby stars.

Enter, stage left: physicist George Gamow.

In 1948, Gamow predicted that right after the Big Bang, the gases in the universe would have been quite hot — plenty hot enough to emit strong blackbody radiation, without any help from nearby stars.

Wait a second…what the heck is blackbody radiation?

That’s just astronomy speak for radiation from an opaque, non-reflective, heated object. That is, a hot object that’s not see-through.

If an object is a “blackbody,” then the radiation it emits will follow a curve like this:

All blackbody objects emit radiation across the entire electromagnetic spectrum, from radio waves to gamma rays. But depending on the object’s temperature, its radiation will “peak” — that is, be the strongest — at different wavelengths.

But how do we know if an object is a blackbody?

Well, as yourself: Can you see through a star? How about a window?

A star is not see-through. It’s opaque, so yes, it’s a blackbody. Its radiation is blackbody radiation. A window, though, is see-through. So it doesn’t emit blackbody radiation.

(What about a mirror, you ask? No, that’s not a blackbody, because it also can’t be reflective.)

Anyway…back to the CMB.

In 1949, physicists Ralph Alpher and Robert Herman noted that if something from that early universe emitted its own radiation, the radiation would be redshifted quite a bit by the time it reached instruments on Earth.

In fact, this radiation would be redshifted all the way to the microwave part of the electromagnetic spectrum. Alpher and Herman predicted that it would appear to us Earthlings to have a temperature of only 5 K.

Huh…that’s kinda close to 2-3 K. At least, closer than any star could possibly get.

Now, back to the mid-1960s.

Around the same time that Penzias and Wilson were cleaning pigeon droppings out of their radio receiver, Robert Dicke at Princeton noted that newly developed techniques might just be good enough to detect this faint radiation.

Penzias and Wilson realized that the strange signal they were getting was, in fact, radiation from the early universe. They won the Nobel Prize in physics in 1978.

But it wasn’t until 1990 that astronomers were able to confirm this discovery.

Penzias and Wilson were able to detect radio waves from the early universe. But this early radiation is spread across radio, microwave, and infrared — and it’s strongest in the infrared.

Infrared radiation, more commonly known as heat, gets absorbed by Earth’s atmosphere and never reaches ground instruments. Astronomers had to wait until they could get telescopes into space.

And they weren’t disappointed.

Satellite measurements confirmed that this “background radiation” had a perfect blackbody curve:

Its apparent temperature was also close to the original prediction, at 2.725 ± 0.002 K.

Remember, though, that this early-universe radiation wasn’t really 3 Kelvins. That’s how we Earthlings observe it, thanks to the enormous redshift. Its actual temperature would have been about 3000 K. That’s on the order of a very cool red dwarf star.

This faint afterglow from the Big Bang became known as the cosmic microwave background, or CMB.

And can I just say, isn’t it absolutely incredible that, as early as the 1930s, such a groundbreaking concept was l predicted…and then sure enough, decades later, it was observed?

That is the essence of astronomy. The existing body of research can lead to new, groundbreaking predictions. And if we’re right…we may have to wait decades for advancements in observing technology, but one day, we can confirm those predictions.

This evidence for the CMB gives cosmologists a great deal of confidence in our current understanding of the universe because, not only does theory match observation, but theory accurately predicted observation decades in advance.

Next week, we’ll explore what this early universe was like.

Did I blow your mind? 😉