I’ll admit it: when I hear something like “the shape of space,” my first thought is, whaaaaa?

It’s hard to talk about the science behind space itself because we first have to wrap our minds around what that even means. What are we talking about? The shape of what? What even is space?

Here’s the first thing we need to understand: we are talking about the fabric of the universe itself.

You know how sometimes we use the colloquialism “the vacuum of space”?

Yeah, that’s what we’re talking about. Not any of the stuff that’s in it — the matter or energy, stars or planets. The actual vacuum. The emptiness itself.

And now we’re about to talk about something mind-bendingly weird: the shape of that emptiness.

Let’s start by imagining a bouncy ball.

Yes, a bouncy ball. (I promise I’m going somewhere with this.)

Now, imagine a drawing of an ant on that bouncy ball.

(Yup, still going somewhere with this.)

The drawing of an ant is two-dimensional. It exists only on the surface of the ball. It has no third dimension; it can’t come to life in our three-dimensional universe. But imagine that, within its two-dimensional world, it’s an actual living ant.

This two-dimensional ant can travel on the surface the bouncy ball. Because it’s two-dimensional, it can only move right and left, backward and forward. It can’t perceive the world beyond the surface of the ball. That surface is all it knows.

If the ant travels across the surface of the ball, it will eventually realize that it has been everywhere in its two-dimensional universe because its footprints cover the whole surface. The ball’s surface is finite. There’s only so much area the ant can cover. But because it is the surface of a sphere, it has no edge.

This two-dimensional universe would have no center, either. The ball has a center, but that center isn’t located on the surface and doesn’t exist within the ant’s universe.

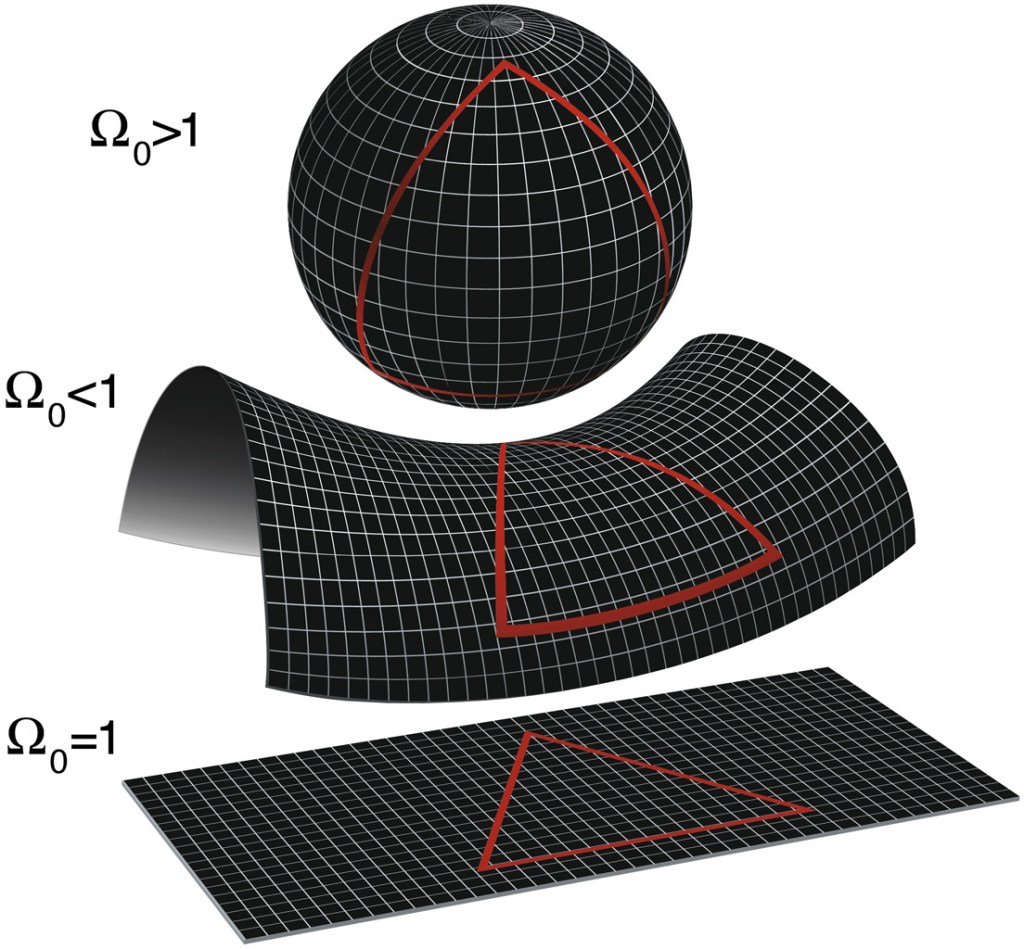

In theory, a three-dimensional universe like our own could be curved back on itself like this. It’s one of three possible types of curvature our universe could have…

A spherical universe would have positive curvature. It is the only shape that would mean a finite universe: a universe whose inhabitants would one day find they had traveled everywhere.

A flat universe, on the other hand, has zero curvature. In order to be finite, it would need an edge and therefore a center. And as we found from studying the cosmological principle, our universe can’t have an edge or a center. So a flat universe would be infinite.

The other possible type of curvature is negative curvature. Space in such a universe would be “saddle-shaped.” This type of universe is also infinite.

What would it be like to live in these universes, you ask?

Well, a flat universe obeys Euclidean geometry — that’s the normal geometry we learn in middle school, with lines and angles and shapes that exist on flat paper.

In a flat universe, a straight line is a straight line. No issue there.

In spherical (positively curved) or hyperbolic (negatively curved) universes, though, a “straight” line will insist on curving. Lines in a spherical universe curve back in on themselves, and lines in a hyperbolic universe stray apart from one another.

To picture this, you can imagine a pair of bugs (ants, flies, anything — the graphic below uses flies) crawling on each surface:

At small scales, the kinds of distances that matter to our daily lives, geometry would work pretty much the same way you’re used to. It’s only when you start observing the positions and motions of distant galaxies that things start to get weird.

In a positively curved universe, lines of sight will converge together at great distances. The farther out you look, the less space is in your field of view. So you see fewer galaxies.

And in a negatively curved universe, lines of sight will diverge at great distances. So, the farther out you look, the more space is in your field of view — more so even than in a flat universe! So you’ll see waaaaay more galaxies than you would in a flat universe.

Still confused? To understand the spherical universe, it might help to imagine the spherical nature of our own Earth.

For the moment, let’s set aside the fact that humans have developed the technology to go to space. Without that technology, we live within the confines of our planet’s crust layer and atmosphere. We can’t go beneath the Earth’s crust to its molten mantle; we can’t (without technology and life support) venture beyond the atmosphere.

In this way, we’re like three-dimensional ants crawling on the three-dimensional surface of a spherical universe that curves around on itself.

Now, let’s take a look at the geometry of latitude and longitude.

Look at longitude. If you were to start at the Earth’s equator and walk in a straight line toward the north pole, you would perceive your own path as a straight line. But if a friend did the exact same thing, starting from a different location on the equator, you’d meet at the north pole.

You both started from the equator. You both took a path that was at a right angle to the equator. And yet you both ended up in the same place.

That’s not possible in a flat universe. Your paths would have been parallel, and they would not have converged.

A negatively curved universe is the opposite — imagine flaying the surface of the Earth open like a saddle. Now, longitude lines diverge infinitely, never to meet again (and never parallel, either).

So…which is it, then? What kind of curvature does our universe have?

For now, I’ll spoil it for you: current measurements indicate that our universe is probably flat.

But that was one of the most pressing cosmological questions of the 20th century — and next up, we’ll dive into that story!

Did I blow your mind? 😉