Sept 2024: This post has been updated and republished from Sept 2017.

First of all, my apologies for missing the last few weeks of posts. I’ve been completely bogged down with physics homework!

(Ironic that I’m missing physics-related posts in order to work on…physics. But my blog is technically an extracurricular, no matter how much of a passion project it may be.)

This week, we’re deviating a bit from our regularly scheduled cosmology programming — because there’s an annular solar eclipse coming up on October 2!

This eclipse will only be visible in the southern Pacific Ocean and across the very tip of South America. But if you happen to be one of the lucky people in its path, this post is for you.

So…what exactly is an annular solar eclipse?

The annular eclipse is not to be confused with an annual eclipse. When my dad first got excited about it back in 2012, preparing us for the spectacular sight of a solar eclipse in May, I wondered why the heck we hadn’t done this every year before. I’d just never heard the word “annular” before!

It means, in short, exactly what you see above. The sun forms a ring of light around the moon, known in fancy astronomy terms as an annulus. Annulus, annular…you get my drift.

But why? Why shouldn’t the eclipse above appear more like the famed total solar eclipse — which is coming up in August 2026?

Like all solar and lunar eclipses, it has to do with the moon’s orbit.

The moon’s orbit is not a perfect circle. It’s actually what we call an ellipse.

This diagram is showing conditions that are very favorable for an annular eclipse.

Because of the moon’s elliptical orbit, it swings in closer to the Earth on one side of its orbit and farther away on the other side. When it’s closer, we say it’s at perigee, and when it’s farther, we say it’s at apogee.

Have you ever noticed that objects far in the background of your sight look smaller than closer objects, even if they’re much bigger?

Somehow, I doubt this guy is actually that much taller than those background trees. Or even as tall as they are.

The way we see the moon works the same way. It appears just a tiny bit bigger when it’s at perigee, and just a tiny bit smaller when it’s at apogee. That tiny bit, in fact, is about 6%.

That 6% is enough of a difference to turn a total solar eclipse into an annular one.

In an annular eclipse, the moon is just a bit too far away to appear large enough to cover the sun completely. Instead, a bright ring of sun shines around the moon.

Let’s take a closer look at how that actually works…

It has to do with the umbral and penumbral shadows.

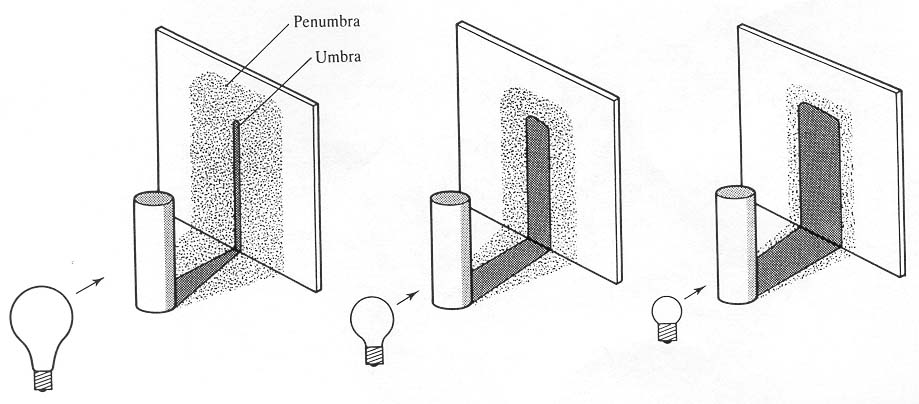

The umbra is simply the darker, inner part of any shadow when the light source is bigger than the object casting the shadow—or there are more light sources.

There’s an area that’s completely blocked from the light source and gets no light. That’s the umbra. But there’s parts outside of it that get some light from the light source, but have some light blocked as well. That’s the penumbra.

And any object can cast both a penumbral and umbral shadow, as long as it doesn’t completely block its light source…

Here, you can see that the bigger the light source compared to the object, the bigger the penumbral shadow will be and the smaller the umbral shadow will be.

Another way you can think of it is by imagining yourself standing between two street lamps.

You cast two shadows, one for each light source. But each of the lamps shines on one of the shadows, making them a bit brighter—penumbral shadows. Any place where the two shadows cross, you’ll get an umbral shadow because no light is falling there.

So, here’s what happens during an annular solar eclipse.

(I wish this diagram showed the sun, just to make it more complete — but the sun is just off to the left, casting the shadow.)

An annular eclipse happens when the moon is too far away in its orbit for the umbral shadow to actually touch the Earth. Instead, we get an “antumbra,” because we never do get “totality.”

Anywhere outside the path of the antumbra, we’ll get a sight much like we would in the penumbra of a total solar eclipse. If you’re standing in the penumbra, it doesn’t matter if the eclipse is total or annular—you’ll still just see a “partial” eclipse.

So…what exactly is the difference between an annular solar eclipse and a partial solar eclipse?

The last annular eclipse I saw was back in May 2012 — and I was, in fact, located within the penumbral shadow. I never saw the ring of the sun surround the disk of the moon, and I didn’t understand until much later that an annular solar eclipse isn’t the same as a partial solar eclipse.

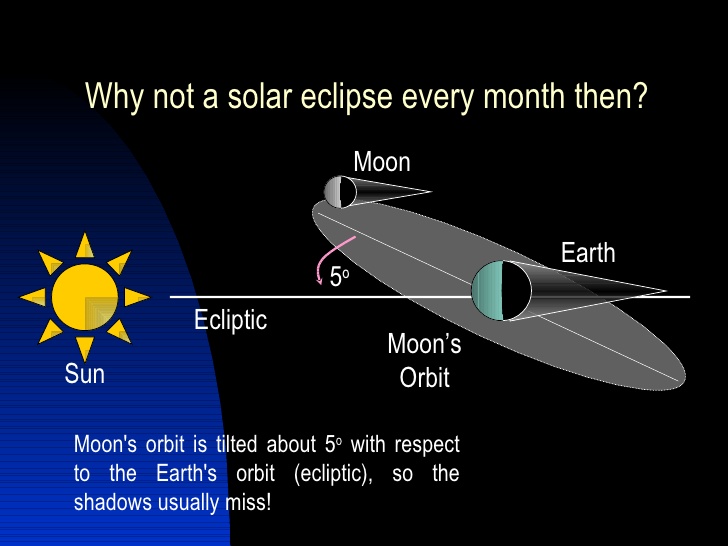

Anytime we get a partial eclipse rather than a total or an annular, it’s because of the tilt of the moon’s orbit.

In this image, we see the moon’s orbit inclined at a small angle to the plane of the Earth’s orbit. (Okay, I know — the picture doesn’t depict it as a small angle. But it’s just 5°.)

If the moon’s orbit doesn’t carry it precisely in front of the sun in the sky, then it won’t cover the sun. The moon’s orbit must line up with the ecliptic — the path the sun traces across the sky — just perfectly.

As the moon loops around the Earth, it naturally crosses the plane of the Earth’s orbit. But it has to cross that plane at a time when it is also located directly between the Earth and the sun in order to produce an eclipse.

A partial eclipse is when it just doesn’t line up perfectly. The moon partially covers the sun…but not all the way.

We see a “total” annular eclipse when everything lines up perfectly, but the moon is at apogee: the moon crosses directly or almost directly in front of sun, but it’s too far away from Earth to completely cover the sun’s disk in the sky.

This October 2005 APOD photo doesn’t show a perfectly centered moon, of course. But we do see a complete ring around the moon, making it a “total” annular eclipse.

Like I said before, though, the upcoming eclipse will only be a “total” annular for a tiny population in the tip of South America. Other observers in the southern hemisphere will be within the penumbral shadow. They’ll see a partial eclipse, like I did.

Here’s what I saw…

Partial or not, it was just as amazing to see. We set up telescopes on our neighbor’s front lawn—he had a better view of the eclipse than we did—and sat outside for a few hours as we watched the moon’s disk creep across the sun.

It always surprises me how hot an event the solar eclipse is. After all, it does mean standing under the sun for hours on end!

During a total solar eclipse, though, it certainly doesn’t stay hot — and you can find out just what to expect in my post on solar eclipse sights, which I recently touched up and reposted for the total solar eclipse in April 2024.

(And next time I find time for a post around my homework, we’ll be back to our regularly scheduled programming on cosmology.)

Did I blow your mind? 😉