In theoretical physics, there are countless theories as to what dark matter is. But how do we know it’s not a wild goose chase?

Technically speaking, we don’t. But fortunately for us, this question comes back to one of the most fundamental scientific principles…

The simplest answer tends to be the right one.

Okay, I hear ya — in what universe is the notion of dark matter simple?!

Don’t worry, I’ll get to that!

But first, let’s explore an example of that fundamental principle…in the form of one of the ancient Greek models of the universe: Claudius Ptolemy’s epicycles.

Ptolemy found planetary motion to be quite perplexing, and I’ll show you why…

Believe it or not…that’s Mars, photographed nightly.

Why the heck is it traveling in a loop?

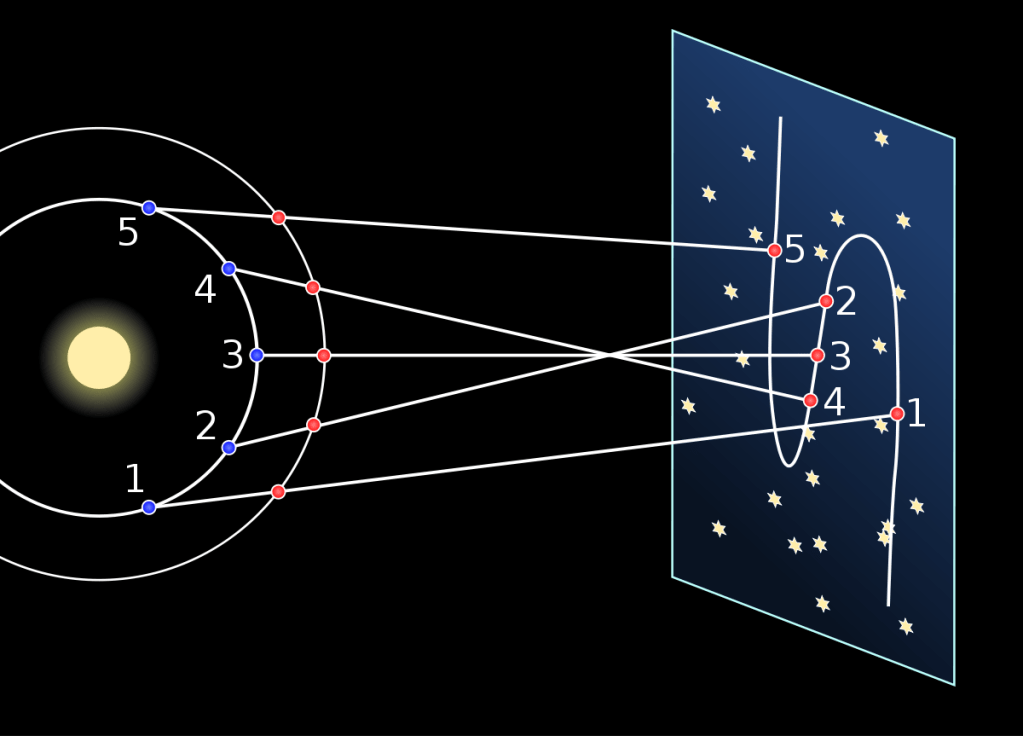

In Ptolemy’s time, the Earth was thought to be the center of the universe, with the sun and planets orbiting it. Ptolemy tried to predict Mars’s retrograde motion — and that of the other planets — by designing a model of the universe with epicycles and deferents.

In this model, the deferent is a circle around the Earth. Smaller circles called epicycles move on the deferent. And a planet sits in a fixed position on the epicycle, and rides it in loops around the Earth.

See how this model attempts to explain retrograde motion?

There’s just one problem: It doesn’t work.

Ptolemy’s model failed to accurately predict the motions of the planets. So…he added even more epicycles.

But no matter how many epicycles Ptolemy added, he couldn’t get his model to predict planetary motion — because epicycles are not the answer.

More than a thousand years later, Nicolaus Copernicus proposed an incredible notion: that perhaps the sun, and not the Earth, is the center of the universe.

(He was still wrong about the “universe” bit, but to the classical Greeks, the terms “universe” and “solar system” were one and the same — no one had even thought to consider we live in a galaxy yet.)

Copernicius’s model did what no previous model could: explain retrograde motion simply and elegantly.

If the Earth and Mars both orbit the sun, then the Earth can catch up to and pass Mars every now and then. When that happens, Mars briefly appears to move backward.

And there you have it…simple retrograde motion, no epicycles required. All we had to do was set the sun at the center of the solar system.

Now, you see what I’m getting at? Ptolemy’s model attempted to solve a problem by adding complexity. Copernicus’s model solved that problem by altering the simplest of assumptions.

What does that have to do with dark matter, then?

Dark matter was hypothesized to explain the rotation curves of galaxies, as you see below:

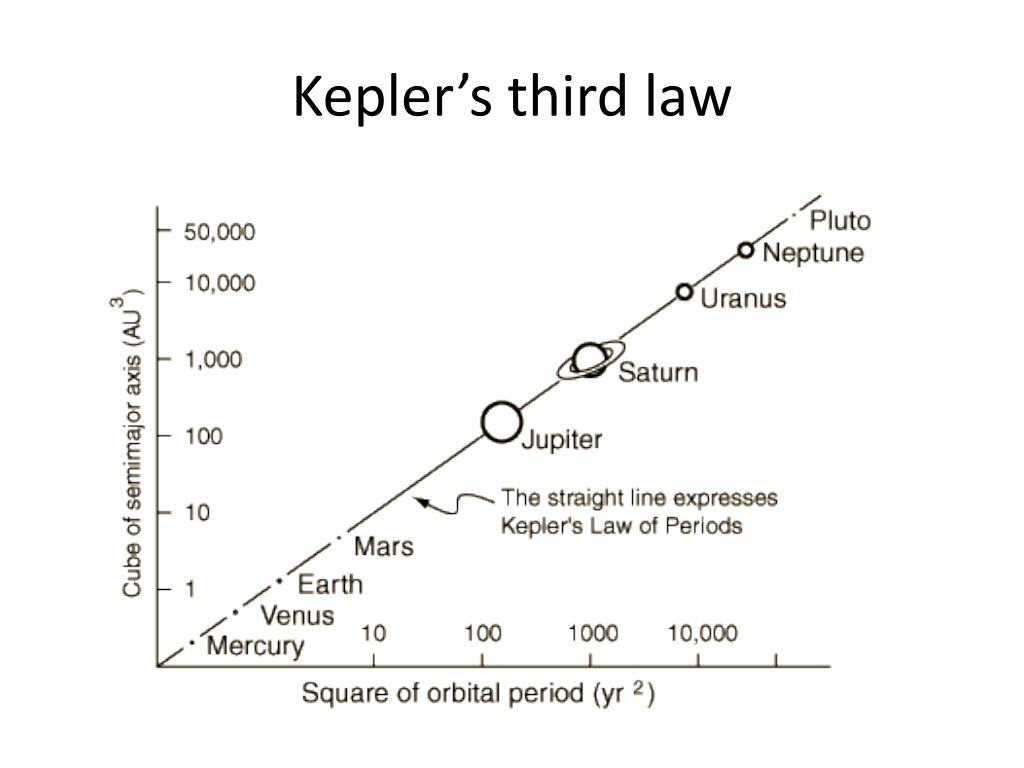

I’ve gone into detail about rotation curves before. The long and the short is that, according to Kepler’s laws of orbital motion, galaxies’ shapes don’t make any sense.

In particular, we see spiral galaxies as beautiful, clear pinwheel shapes. But according to Kepler’s laws, the stuff on the outside should orbit the center much slower than the stuff on the inside.

For objects as old as galaxies to appear to us as pinwheels, that must be a stable shape for them — one that lasts millions, even billions, of years. In short, they should literally rotate like a lawn pinwheel.

And here, we run into a problem…

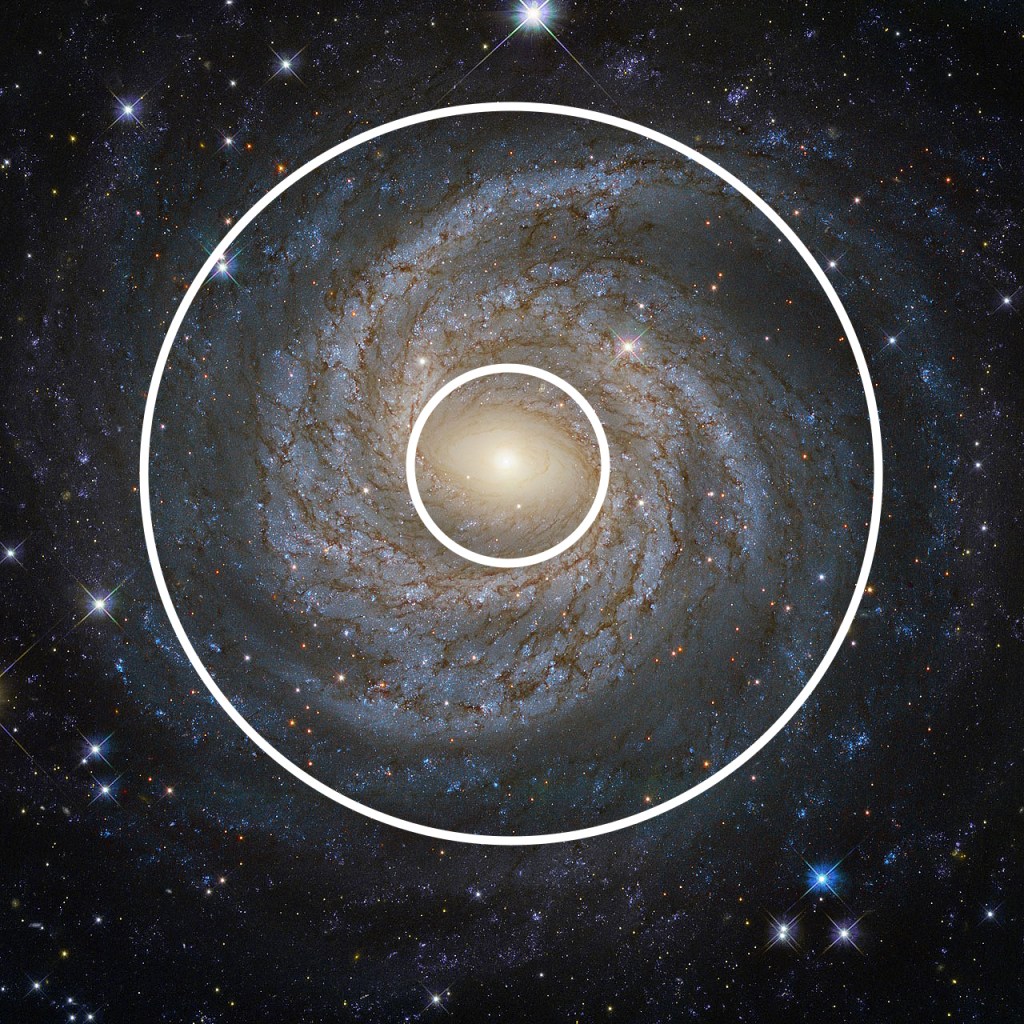

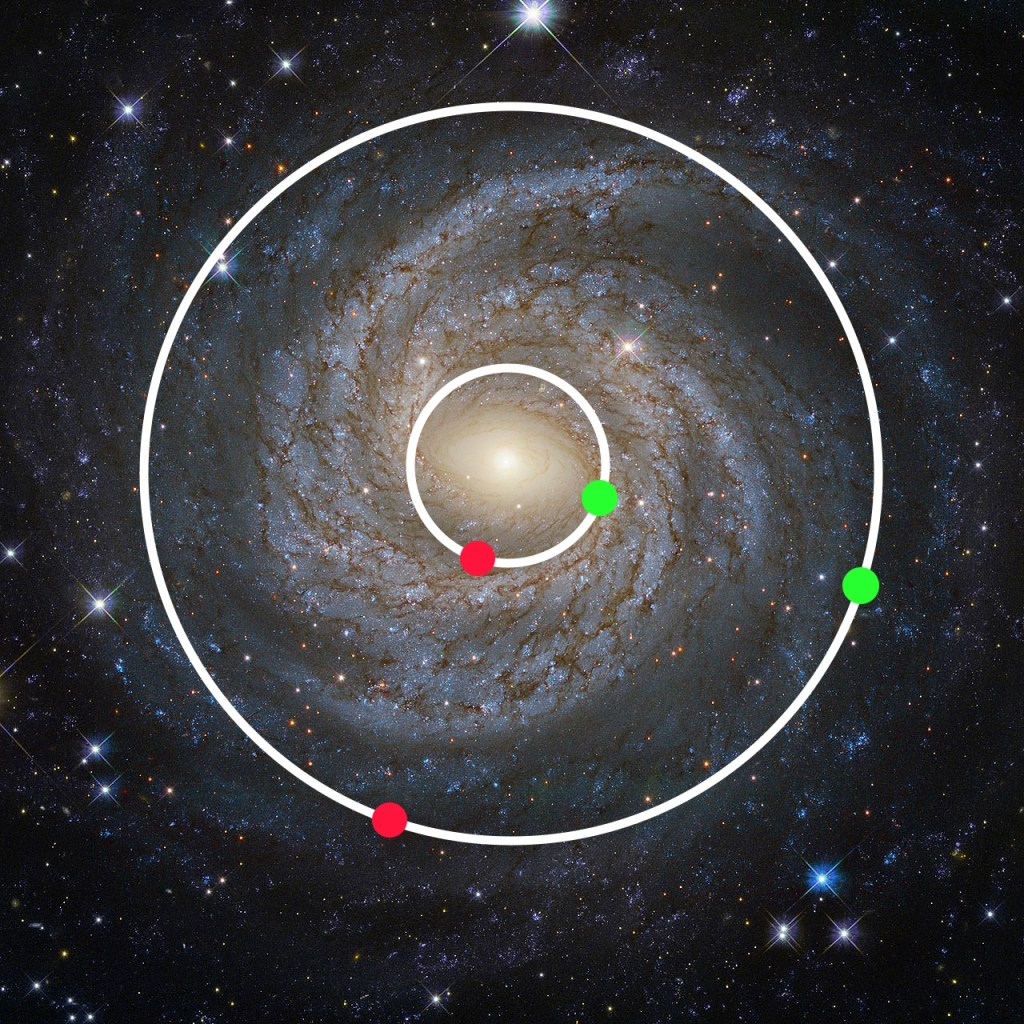

Here’s a nice, face-on spiral galaxy.

Now, let’s establish some geometry. Keeping in mind that a galaxy’s rotation is the orbital motion of its stars, let’s draw the orbital path of a star on the outside and the orbital path of a star closer to the nucleus.

The circumference of the inner circle is the distance that a star near the center needs to travel.

The circumference of the outer circle is the distance that a star near the outer edge needs to travel.

In order for the galaxy to maintain this perfect spiral shape over millions or billions of years, it needs to rotate as if it is a solid object.

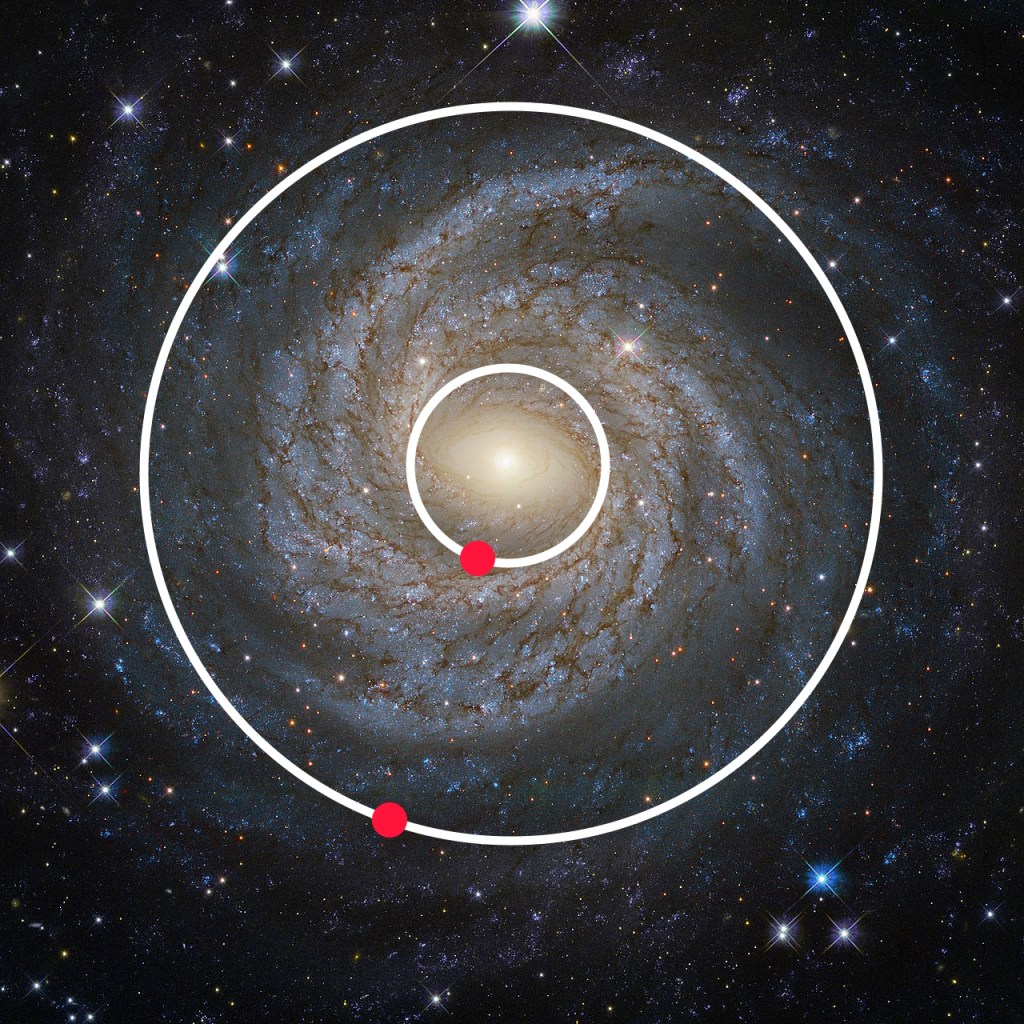

Now, let’s add a little something to help us track the galaxy’s rotation.

Here are two red dots at roughly the same angle from the galactic center. As these dots continue on their orbits, they need to remain at that same angle — just like how the blades of a lawn pinwheel would maintain their angle.

Now, here are two green dots, representing the future locations of the two red dots:

Notice that the green dots are both at the same angle from the center, just like the red dots. Now, both red dots need to travel to meet both green dots in the same amount of time.

The dots on the outside simply have a greater distance to travel.

In order for a spiral galaxy to maintain a pinwheel shape, the stuff on the outside needs to not only keep pace with, but orbit faster than the stuff on the inside.

But…wait a second. Didn’t we say that according to Kepler’s laws of orbital motion, stuff on the outside orbits slower than stuff on the inside?

Yup.

Kepler’s third law states that the speed of an orbit depends on its distance from the sun. A closer orbit is faster; a more distant orbit is much slower.

Kepler’s laws definitely work. But they were originally conceived to describe planetary motion, before astronomers had any idea that galaxies were a thing.

Now, gravity doesn’t work differently for stars and for planets; Kepler’s laws should be able to describe both planetary motion and the rotation of a galaxy. The problem lies with a simple premise.

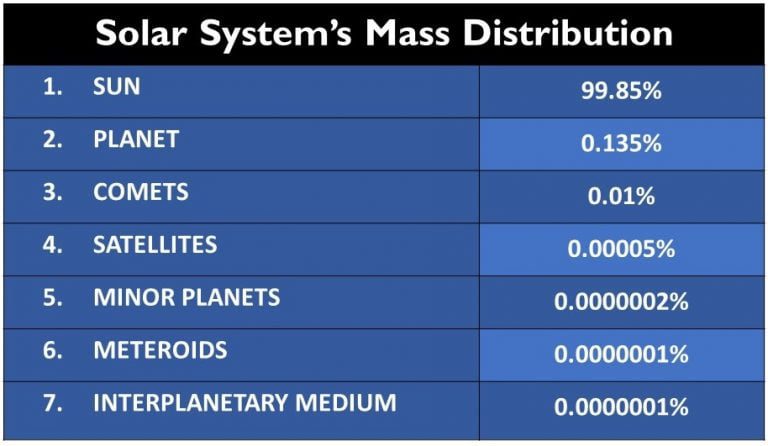

Kepler’s laws assume that most of the mass of a system (read: solar system or galaxy) is concentrated at its center.

In a solar system, that’s true. 99% of the mass of our solar system is concentrated in the sun.

In a galaxy…that’s not the case.

The material in a galaxy — stars, dust, gas — is spread throughout its disk much more smoothly than in a solar system. But even then, there still isn’t enough visible matter in the outer reaches to account for the sheer speed of those outer orbits.

Visible matter being the operative term.

That’s where dark matter comes in.

Since it was originally hypothesized, the existence of dark matter has been confirmed numerous times over. We see its effects on hot intra-cluster gas of galaxy clusters, such as in the Coma cluster:

This cluster is filled with gas so hot that, according to Newton’s laws, its atoms should have escaped the cluster altogether. That is, unless an unseen mass of dark matter holds the gas captive.

Dark matter is also the best explanation for cases of seemingly excessive gravitational lensing, like this:

While baryonic (ordinary) matter is perfectly capable of distorting space-time enough to “lens” distant galaxies, there isn’t enough matter visible here to account for the sheer strength of this lensing effect.

Clearly, matter we can’t see — dark matter — is pulling its own weight to add to the effect.

The effects of dark matter have been observed in so many cases that it has emerged as the simplest explanation.

In theory, we could try to update general relativity — the framework that explains gravity — to avoid the need for dark matter. But the changes would need to account for all of the apparent effects of dark matter.

Here’s the crux…

Gravity is universal. Dark matter is not.

Gravity is associated with all matter. But not all galaxies appear to contain dark matter.

For example, here’s NGC 1052-DF2, a galaxy that doesn’t conform to any established categorization:

This galaxy is weirdly transparent — those bright, fuzzy specks you see in its midst are actually distant, background galaxies!

Even stranger, this galaxy seems to be missing most, if not all, of its dark matter.

If dark matter doesn’t exist, then how do we explain why gravity behaves differently with different galaxies?

Updating general relativity to explain all of dark matter’s effects without dark matter would be like adding tons of Ptolemy’s epicycles. It attempts to solve the problem by adding complexity.

Dark matter may be whacky and elusive, but — bizarre as it is to say — it’s the simplest explanation.

Next up, we’ll explore a plethora of possible theories as to what dark matter could be!

Did I blow your mind? 😉