In the grand scheme of the universe, planets are small. But that doesn’t make them unimportant.

We live on a planet. Understanding how planets form and how the evolution of their solar system affects them is critical to answering one of humanity’s most pressing questions…

Are we alone?

Do we live in a universe teeming with life; do other beings on distant planets wonder if they are alone? Or is the universe a desolate and empty place?

We’ll come back to those questions eventually, in future posts. But first, let’s familiarize ourselves with the solar system, our home in the cosmos.

First things first…how do the planets move?

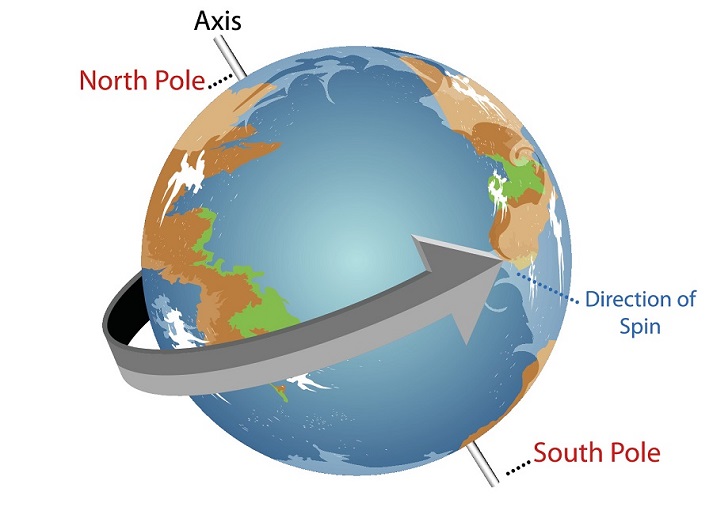

You may already know that in one day, the Earth rotates about its axis…

This is, in fact, what causes day and night. Half of the Earth is always illuminated by the sun; the other half is always in shadow. As the Earth rotates, different regions of the surface experience daylight and night:

And, as you may also know, the Earth revolves around the sun. That’s a fancy word for saying it orbits. It travels around the sun once per year:

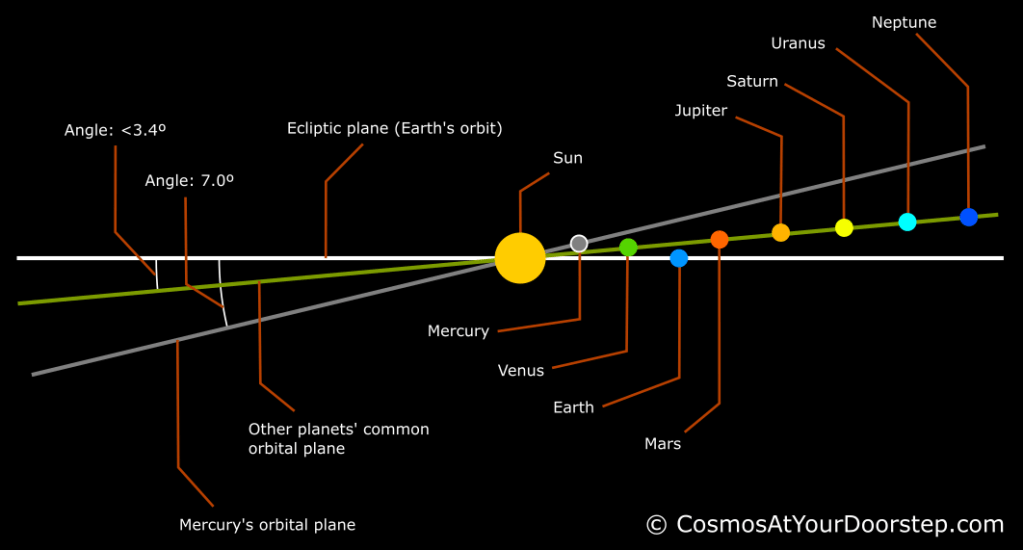

Wait…what’s that plane it’s orbiting on?

That’s the ecliptic plane, and we’ve covered it before on this blog — but that was years ago. It’s basically a fancy term for the plane of Earth’s orbit.

And all the other planets closely follow the ecliptic, too.

Our solar system is like a big disk: all the planets orbit the sun in roughly the same plane…

…but not exactly the same plane. They’re tipped, just a little bit. Not a lot; most are tipped by no more than 3.4º. Mercury is a bit of an exception; it’s inclined by a whole 7º with respect to the ecliptic.

Below, you see the solar system edge-on:

Keep in mind that the difference isn’t really that dramatic. I probably drew Mercury’s orbital plane at close to a 30º angle. I wanted to exaggerate it so you can see what I mean by the orbits being inclined relative to the ecliptic.

In reality, the other planets don’t exactly share a common orbital plane, but it’s close enough that I drew them as one here. I didn’t want to make the graphic super busy with a ton of lines!

As we know from Kepler’s laws of planetary motion, the planets also orbit the sun at different speeds. The farther out they are, the slower the speed.

Like Earth, the other planets also rotate about their axes (plural for axis):

You know what that means?

Earth isn’t the only planet that experiences day and night.

Notice, though, that all the planets rotate at different speeds. Jupiter’s day is shorter than half an Earth day; Venus, on the other hand, rotates so slowly that one day is as long as about 8 Earth months. And its day is actually longer than its year. Venus takes longer to complete one rotation about its axis than one revolution around the sun.

Also note that several of the planets rotate at an angle. Mercury, Venus, and Jupiter are nearly upright, but Earth, Mars, Saturn, and Neptune are tilted between 20º-30º. And Uranus is a total oddball — more on that in a sec!

In general, everything rotates and revolves in the same direction: counterclockwise, as seen from north.

There are a couple of exceptions to the rule, though. We’ve got two contrarian planets: Venus and Uranus.

Venus doesn’t just rotate ridiculously slowly — it rotates backwards.

And Uranus rotates sideways. Even its ring system — not drawn here — orbits Uranus at an angle almost vertical to the ecliptic.

In future posts, we’ll take a dive into the peculiarities of these planets and try to explain the observations we make today. But for now, let’s make a general survey of what the planets are like.

We have two distinct types of planets: terrestrial and Jovian.

In fact, technically, we can divide Uranus and Neptune into their own third category: ice giants. (More on that in future posts!)

We count Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, and the moon (yes, the moon too) among the terrestrial worlds.

In general, we count Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune among the Jovian worlds.

The word “terrestrial” comes from “Terra,” the Latin name for Earth. And, indeed, the other four terrestrial worlds all have a set of important characteristics in common with Earth: they are small, dense, rocky worlds, and they have little to no atmosphere.

But…wait a second. Whaddya mean, they have little to no atmosphere? What about the Earth? It totally has atmosphere! If it didn’t, we wouldn’t be here to talk about it!

Compared to the gas giant worlds, the terrestrial planets really do lack atmosphere.

Here’s a peek at the interiors of the Earth, Mars, and the moon:

These worlds have a ton of rock. They’re made up almost entirely of rock. But their atmospheres are extremely thin. Even Earth’s atmosphere is too thin to register at this scale.

Mars barely has an atmosphere; its gravity is too weak to hold onto one even as thin as Earth’s. Mercury and the moon have no atmosphere whatsoever.

Most critically, though…

Terrestrial worlds have surfaces.

There is a distinct boundary where all that rock meets atmosphere…or just the vacuum of space.

Even on Earth, there is a distinct boundary between the surface of the liquid ocean and the air above. You can tell where the ocean ends and the air begins, right? The surface of the waves?

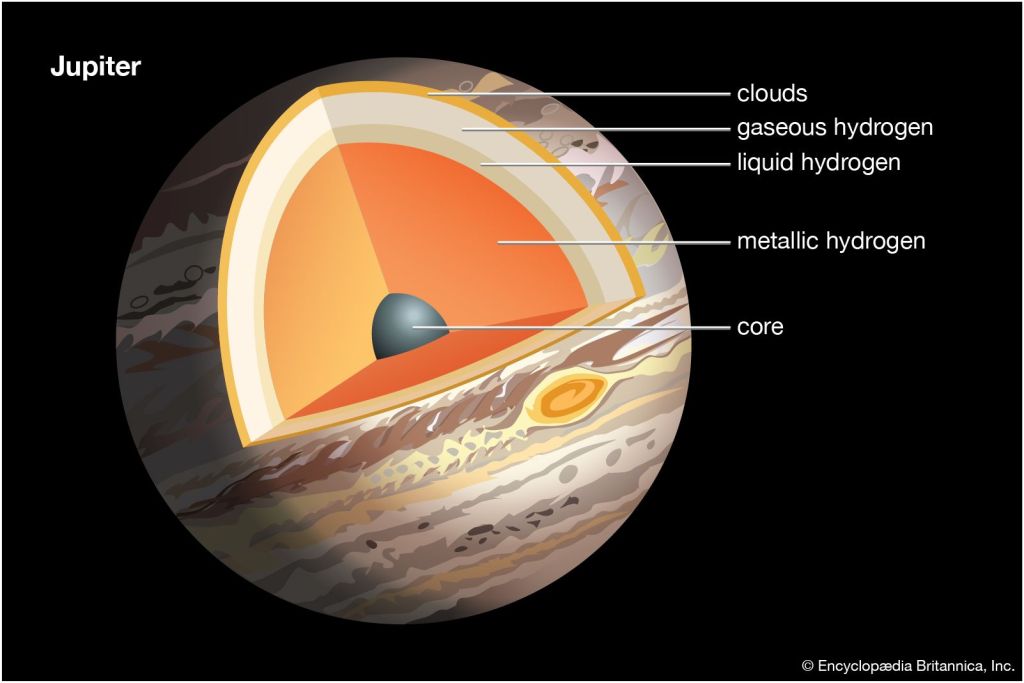

That’s not the case for Jovian worlds. Take Jupiter, for example:

Jupiter does, presumably, have a rocky core. But above that core is a thick layer of metallic hydrogen. Above that layer is a sea of liquid hydrogen. Then a layer of gaseous hydrogen, which blends seamlessly into the clouds of its atmosphere.

Jovian worlds have no surfaces.

That fact plays an important role in our study of the solar system’s history and evolution — because it leads to another important difference between terrestrial and Jovian worlds.

Terrestrial worlds are covered in craters — pockmarks due to collisions with meteorites (space rocks). Jovian worlds are not.

Here’s Mercury’s cratered surface:

And, of course, we’re all familiar with the moon.

Even the Earth has impact craters. Most of them have been erased by Earth’s active geology, but there are still some…like the imaginatively named Meteor Crater in Arizona.

The terrestrial worlds are rocky. When rock slams into rock, we can see the aftermath. But Jovian planets are almost entirely gas and liquid.

They’ve almost certainly been struck by space rocks. But air is fluid. Impacts don’t make craters. They end up looking untouched.

As we’ll see in future posts, impact craters are an important way to determine the age of a surface. The solar system is full of space rocks. Impacts are common. If a region of a terrestrial world doesn’t have many craters, it must not have been around long enough to accumulate them.

That doesn’t mean the planet itself is young, just that the sparsely cratered region of its surface is young. Earth is a prime example: the planet itself is as old as the rest of the solar system, but it’s a geologically active world, its landscape constantly changing. It doesn’t have many craters because most of its surface is comparatively young.

(The atmosphere helps protect us, too — more on that in future posts!)

Jovian worlds may not have impact craters, but they are certainly not gentle places…

Just take a look at Jupiter’s turbulent cloud systems. Its famous Great Red Spot is a storm twice as wide as the Earth that’s been raging for at least 150 years.

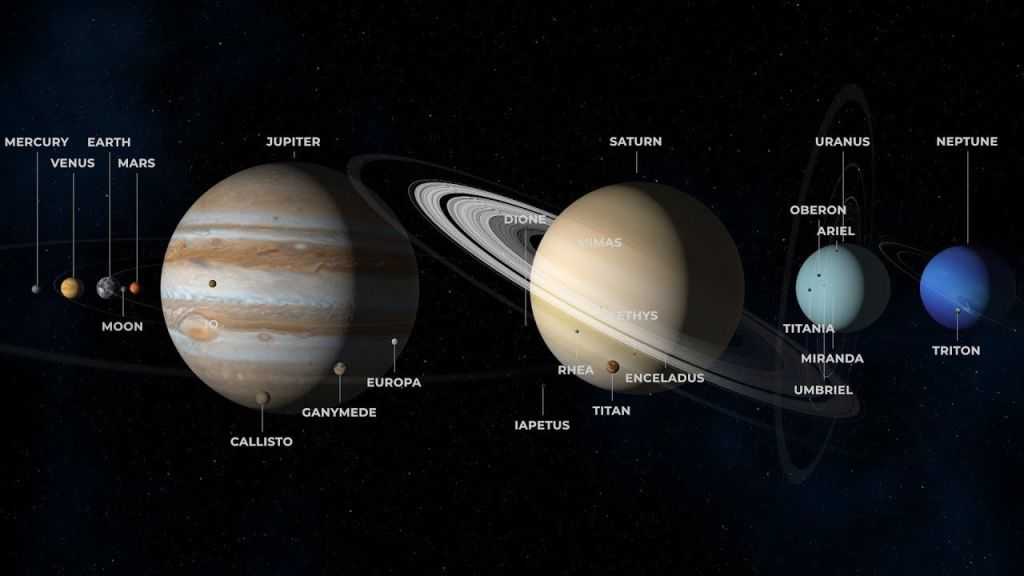

But perhaps the most obvious difference between terrestrial and Jovian worlds is their sizes.

Graphics aren’t always good at making that clear. That’s because the Jovian worlds absolutely dwarf the terrestrial ones. If you draw all the planets to scale, the terrestrial planets are tiny.

How tiny?

Super tiny.

Earth, the largest terrestrial planet, has a diameter of 12,760 km (7926 miles, for my fellow Americans). By contrast, Neptune — the smallest Jovian world — is 49,528 km across (30,775 miles). That’s more than 3 times that of Earth.

Jupiter, for its part, is an entire 142,984 km (88,850 miles) in diameter — a whopping 11 times that of Earth.

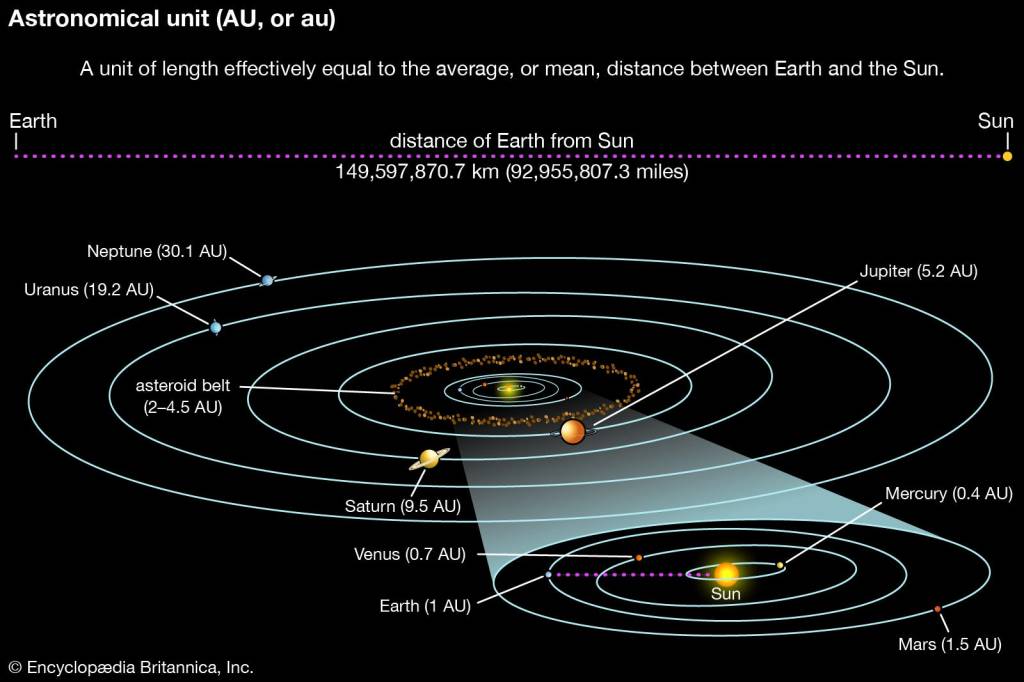

And speaking of sizes…how about distances? If you examine the orbits of all the planets, you’ll note that the terrestrial worlds — the inner planets — are all huddled close around the sun…

…and the Jovian worlds (the outer planets) are distant, and far more spread out.

There’s one more critical difference between terrestrial and Jovian worlds…

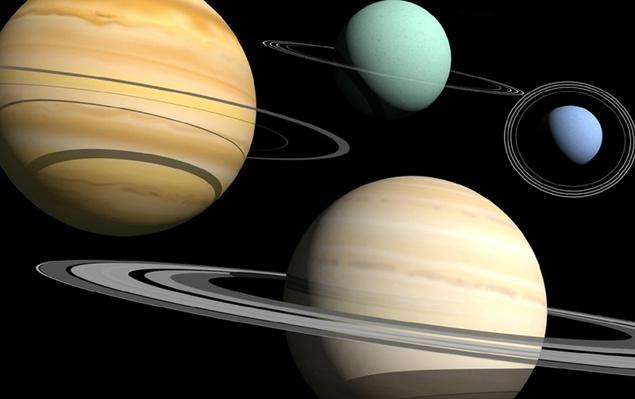

Jovian planets have ring systems. Terrestrial worlds do not.

Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune all have rings. Saturn’s rings are, of course, the most famous, but they all have them.

Earth has no rings, and neither do Mercury, Venus, or Mars (or the moon, for that matter).

But…why?

Why are terrestrial planets so different from Jovian? Why the difference in size, structure, composition, and rings (or lack thereof)? Why are all of the inner planets terrestrial worlds, and the outer planets Jovian?

All of this begs explanation…and as we answer these questions, we’ll uncover the history and evolution of our solar system.

Next up, though, I’ll address the question I know some of you are going to ask me…

What about Pluto?

Don’t worry, I haven’t forgotten about it! But I’ll save that discussion for next time 😉 And after that, we’ll take a closer look at those space rocks we talked about!

Did I blow your mind? 😉