In my last post, we explored the two types of planets: terrestrial (Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars) and Jovian (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune).

Pluto was conspicuously absent from the lineup…especially considering that we took a peek at the moon.

But I’ve got a good reason for that!

Rest assured, I haven’t “forgotten” Pluto. To me, it has simply been reclassified, not “demoted.” There is no hierarchy of astronomical objects; none of them are “better” or “more important” than the others.

In fact, dwarf planets are just as important as planets to the story of the solar system.

We’ll explore that in depth in later posts. But for now, I want to explain why the heck we call Pluto a “dwarf planet.”

First things first: I use the definition of a planet adopted by the International Astronomical Union (IAU). This is the same group that sets the official 88 constellations, used for mapping the night sky.

Here’s the short version. A planet must:

- Orbit a star ✔️

- Have enough mass for its own gravity to force it into a spherical shape ✔️

- Have more mass than that — enough to clear the path of its orbit around the sun ❌

Pluto satisfies the first two conditions. Obviously, it orbits the sun, though its orbit is a bit strange:

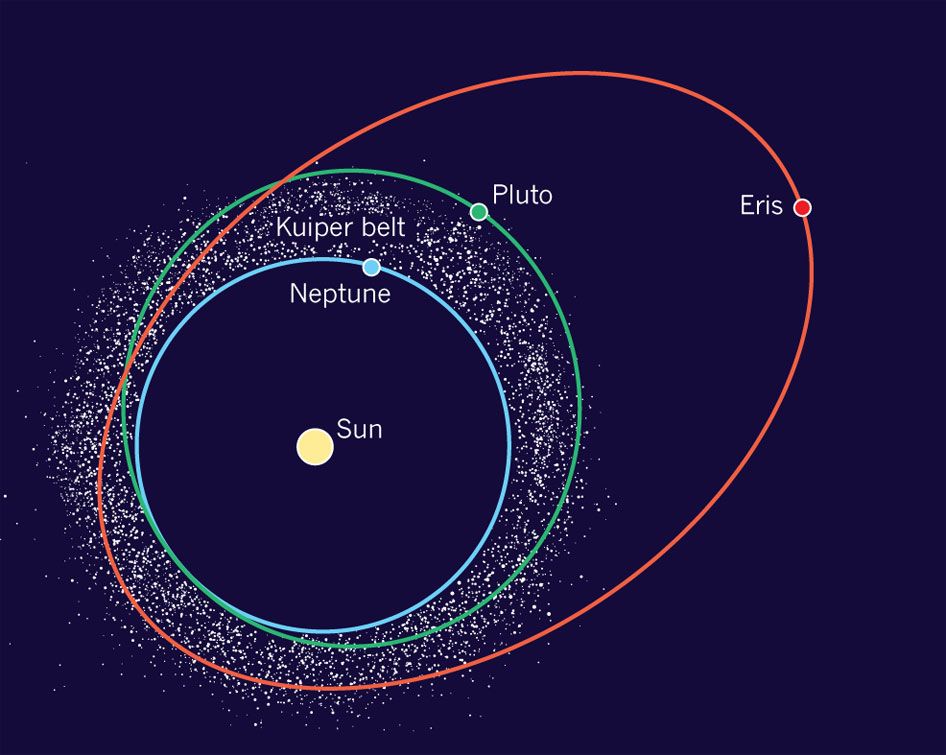

For one thing, Pluto orbits ridiculously far out. Its average distance from the sun is about 39.5 AU (1 AU, or astronomical unit, is Earth’s distance from the sun) or 5.9 billion km.

Compare that to Neptune’s average distance from the sun: 30.1 AU or 4.5 billion km.

For another thing, its orbit is highly eccentric. Every orbit in the universe is an ellipse, but the 8 planets have orbits with low eccentricity, meaning they are almost circular. (More on that here.)

Pluto’s orbit is distinctly an ellipse. Its closest pass around the sun (perihelion) is only about 29.7 AU; the most distant it swings out into the depths of the solar system (aphelion) is 49.5 AU.

(Notice that it actually crosses the path of Neptune’s orbit. None of the planets’ orbits cross one another like that.)

Pluto’s strange orbit is not, in itself, a reason to reclassify it as a dwarf planet. But it does make Pluto unusual. To me, it partially justifies the reclassification: if we consider Pluto a different type of object, the reclassification frees us to study it in a different context and better understand its nuances.

The second condition requires a planet to have enough mass to force it into a spherical shape, like these guys…

…rather than an irregular shape, like these guys:

See, terrestrial objects like asteroids, the inner planets, and Pluto are rocky. And rocks aren’t very fluid at all. They’re about as solid as stuff on Earth gets. They like to stay in the shape they’re in, and not be molded or reshaped.

Imagine the gravity it takes for rock to have no choice but to reshape itself into a sphere?

Gravity means mass. So, a planet must be massive enough to form itself into a sphere. And Pluto can indeed do this. In fact, this is what differentiates dwarf planets from asteroids. Dwarf planets are massive enough to be spheres, but not massive enough to be planets.

So, let’s take a look at that third requirement: clearing the path of its orbit.

You’ll notice, if you examine the planetary orbits in the solar system, that while there is a ton of space debris flying around — more on that later — no planet shares an orbit with an object of similar size.

In other words, Jupiter (for example) isn’t competing for space at the same distance from the sun as a twin Jupiter.

But why is that?

The answer lies, again, with gravity.

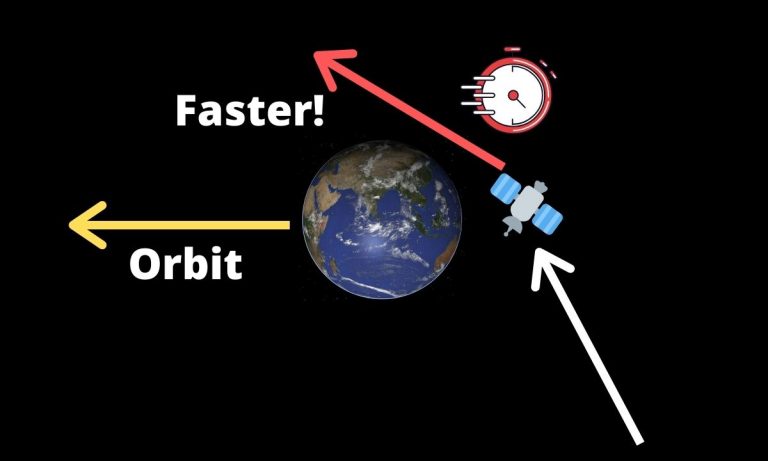

You’re likely familiar with one effect of gravity: causing objects to fall, or sustain an orbit. (In fact, an orbit is just free-falling with enough tangential velocity to keep “missing” the central object; more on that here.)

But are you aware that gravity can also cause a slingshot effect?

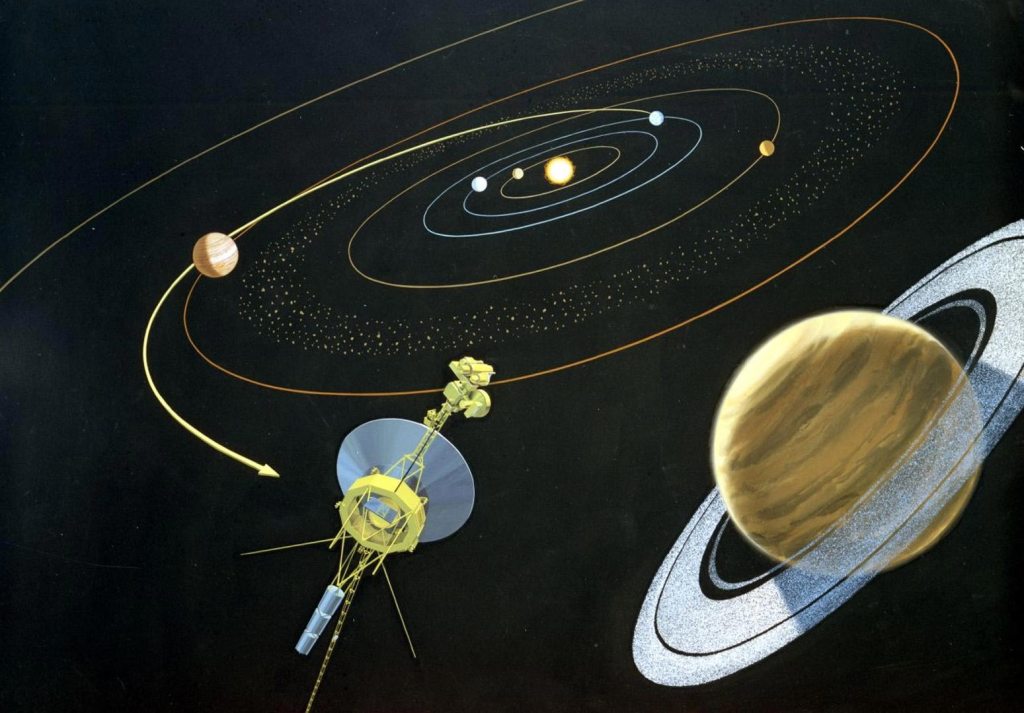

This is a clever way to get a spacecraft into the outer solar system: we use something called a gravitational assist to speed up the spacecraft’s velocity and allow it to overcome the gravitational pull of the sun.

This relies on Newton’s inverse square law for gravity: that the gravitational force increases as the distance between two objects decreases.

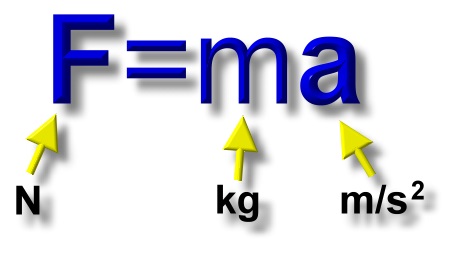

Most importantly…when gravitational force increases, acceleration — change in speed — due to gravity increases. That’s due to Newton’s first law:

This is, in fact, why planets move faster when they swing close to the sun and slower when they’re at the farthest point in their orbits. Kepler’s second law describes this behavior, but Newton’s laws explain it.

But here’s the crux.

If we launch a spacecraft from Earth, it starts out with at least enough velocity to exceed Earth’s escape velocity (the speed necessary to escape Earth’s gravity). But we’ve still got the sun to worry about.

The sun is way bigger than Earth. It’s farther, but its gravity is still strong enough to hold an object as far out as Pluto in orbit — why not one tiny spacecraft?

The sun’s gravity will slow the spacecraft down, to the point where it would take ages to reach the outer solar system…

Unless, say, it swung past Mars.

As the spacecraft closes in on Mars, its acceleration due to Mars’ gravity increases.

We also make sure that the spacecraft closes in on Mars from “behind” — so that Mars’ gravity gives it a firm tug in the direction we want.

Here’s an example of what’s happening here (except Earth is drawn instead of Mars):

I used Mars as an example, but Jupiter is even better at gravitational assists. Its orbit is slower, but its gravity is powerful, so a spacecraft headed out to Saturn would get a nice, strong tug.

Note that a gravitational assist does not pull the spacecraft into orbit around the planet doing the assisting. It’s still exceeding the necessary escape velocity of whatever planet it’s swinging past. But because of F=ma, its acceleration increases, and that slingshots it outward.

What does this have to do with Pluto, you ask?

This is why planets have their own, discreet orbits. It’s why Jupiter doesn’t share its orbit with a twin Jupiter: it either pulls in or slingshots out all the space rocks it encounters. It dominates its orbit. Another planet has no chance to start forming.

Pluto doesn’t do this.

Since Pluto’s discovery, more than 2000 similar objects have been discovered at a similar distance from the sun. And that’s just a tiny fraction compared to what scientists predict is out there.

Pluto doesn’t dominate its orbit. It doesn’t have enough mass — by extension, enough gravity — to slingshot away the “competition,” or to pull all those tiny objects into orbit as moons.

We call Pluto’s family of objects the Kuiper Belt objects, or KBOs — and we will be exploring them in depth later!

But wait, you say. In the graphic above, Pluto doesn’t look like it’s properly contained within the Kuiper Belt. What does that mean? Is it not properly “one of them”? Does the term “dwarf planet” fit as poorly as the term “planet”?

Nope. See, another dwarf planet known as Eris orbits even farther out than Pluto, its orbit definitely not contained within the Kuiper Belt:

In fact, Pluto’s orbit is still largely contained within the Kuiper Belt. And most KBOs have highly eccentric orbits, too — more so than Pluto’s.

Pluto is effectively categorized as the largest of the KBOs, and fairly standard for a dwarf planet.

Scientifically, it’s actually much more useful to sort Pluto into the “dwarf planet” category. Instead of looking like an oddball amongst planets, it looks quite at home among the dwarf planets. Sorting it properly helps astronomers understand the dynamics of the solar system.

Pluto is useful as a dwarf planet. It’s important. It has not been forgotten, and it has not been “demoted” — by classifying it properly, we are that much more able to understand its story.

At the end of the day, it’s just a reclassification. And if, one day, we find that the definition of a planet needs revision, we can always reevaluate Pluto’s place.

Next up, we’ll take a sneak peak at the smaller objects in the solar system: asteroids, and, yes, KBOs!

Did I blow your mind? 😉