When you look up at the night sky on a clear, dark night, it seems as if the stars are glittering like bright thumbtacks on a great canvas above you. (You can get a similar effect — with less light pollution — from a planetarium like the one above!)

In reality, space is not like a canvas, and stars are not like thumbtacks. It would be more accurate to describe us Earthlings as floating in a vast, cosmic ocean.

Astronomers know this. But still, it’s helpful to map the sky in exactly the way it appears to us: as a sphere around the Earth. And so we use a model called the celestial sphere.

Telescopes operate solely based on the celestial sphere: the mechanism that aims the telescope doesn’t need to know anything about how far away an object actually is in the cosmic sea, just where it is in the sky.

That makes the celestial sphere a useful reference tool. Researchers need to communicate with telescope operators and say, “Let’s look over there now.”

And so, everything is mapped on a spherical model that pretends the night sky is a finite globe, inside which the Earth hovers like a bubble.

So…what exactly is the celestial sphere?

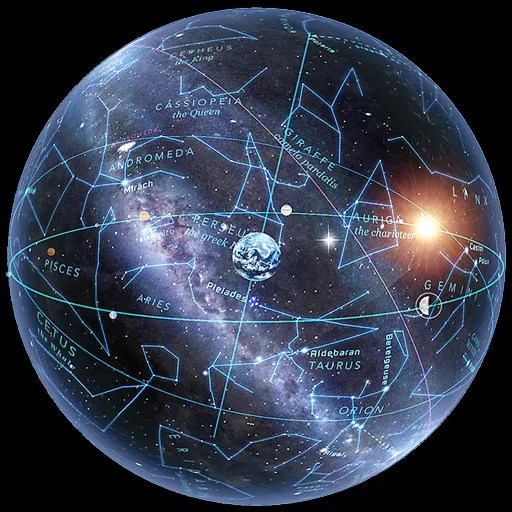

Here it is: a sphere surrounding the Earth, which depicts the entire sky.

In this representation, you can see the sun shining bright, placed exactly along the ecliptic. The ecliptic is an imaginary line that is defined by the sun’s apparent motion around the sky.

You can also see several planets, just the ones that are visible to the naked eye. You’ll notice that they, along with the moon, are also roughly along the ecliptic.

The Milky Way cuts a ring-shaped swath around the entire celestial sphere. This is what our own galaxy looks like to us, from the inside.

Scattered across the celestial sphere’s canvas are the constellations — all 88 that are officially recognized by astronomers!

And last but not least, you can see the straight line that represents Earth’s axis of rotation. It’s drawn plunging through the Earth from pole to pole, and it’s tilted a bit, representing that the Earth does not sit exactly upright relative to its orbit around the sun.

But how to we use this model to navigate the sky?

First, let’s establish our bearings.

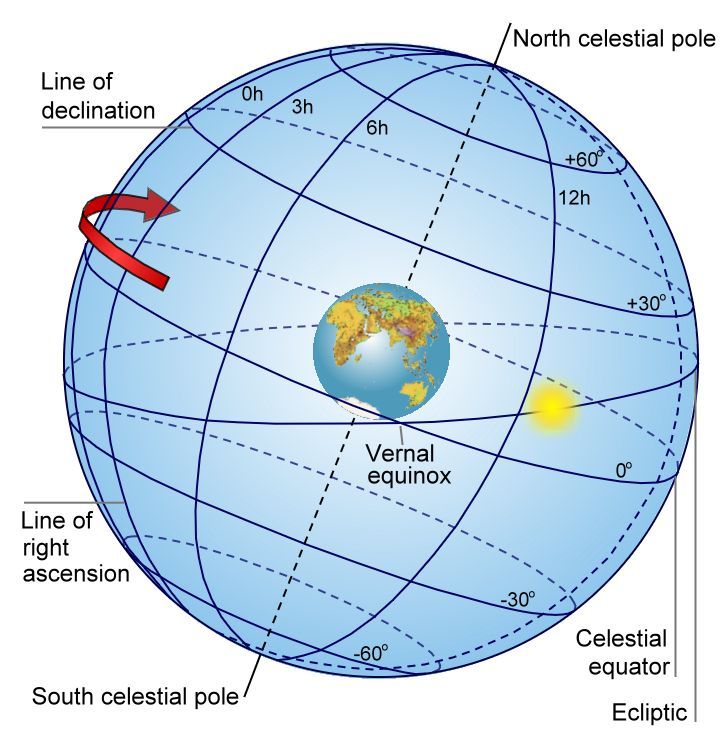

The celestial equator is simply Earth’s equator, projected into space. The same goes for the north and south celestial poles. If Earth’s rotational axis, the dashed line, plunged all the way through the celestial sphere, it would mark the celestial poles as well.

As we noted above, the ecliptic is the imaginary line the sun traces as it moves around the sky. (That’s just how it looks from Earth — in the cosmic sea, this motion is actually the orbit of the Earth around the sun.)

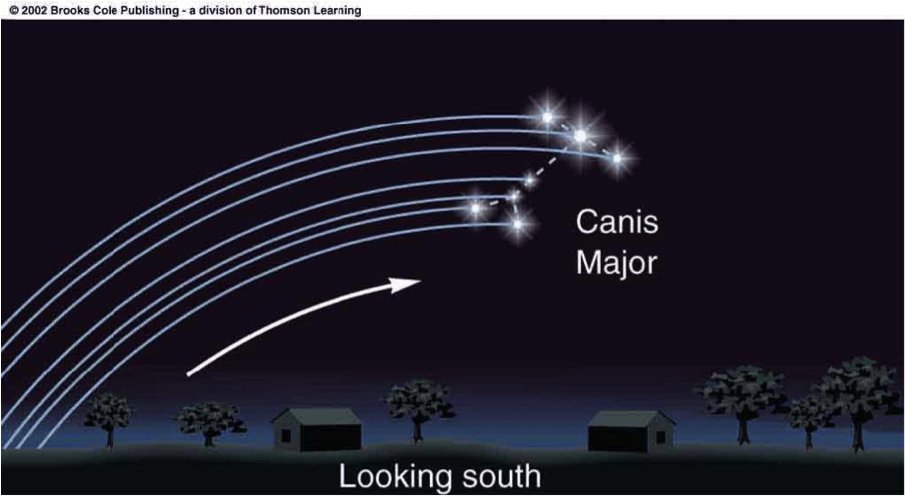

Also note the red arrow, indicating that the celestial sphere is rotating westward. This is actually the eastward rotation of the Earth about its axis. That makes it look like the sky rotates above us in the opposite direction.

Now we can talk about navigation.

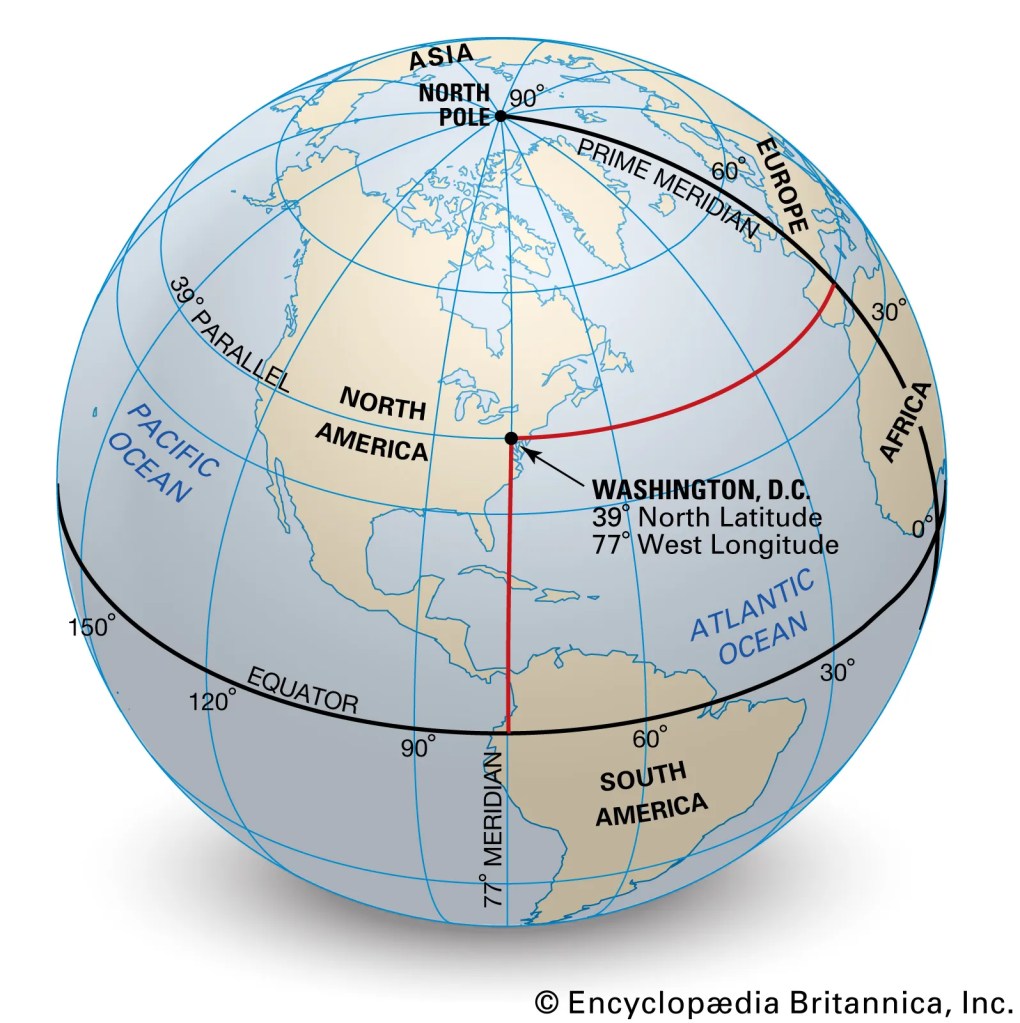

The celestial sphere is used to locate objects in the sky, such as stars, just like how the globe is used to locate places on Earth.

On Earth, we navigate by latitude and longitude. Latitude lines run parallel to the equator and to each other. They are labeled in degrees (°), with 0° being the equator, 90° N being the north pole, and 90° S being the south pole. (Sometimes, negative latitude — “-90°” — with no cardinal direction letter is used to describe southern latitudes.)

Then, we have longitude. Longitude lines all begin at the poles and diverge at the equator, so they are not parallel to one another. They’re more like the ribs of a pumpkin. They’re also labeled in degrees; 0° longitude is the prime meridian. We label a location as, say, 30° W or 30° E to indicate westward or eastward along the equator from the prime meridian.

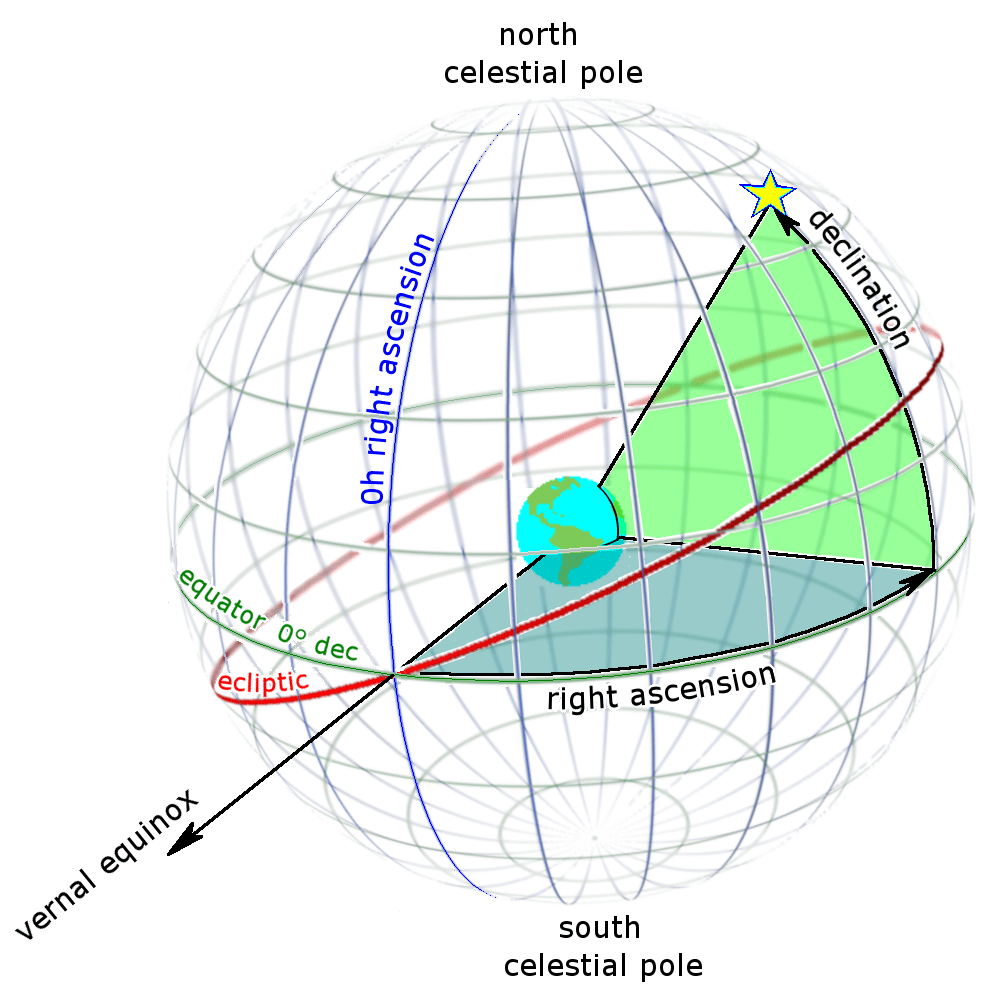

On the celestial sphere, we use declination and right ascension instead of latitude and longitude.

Just like latitude, declination is measured in degrees and has a starting point at the celestial equator. They are also projections of latitude lines on the celestial sphere.

Right ascension, abbreviated RA, is a little bit different. Like longitude lines, RA lines converge at the poles (in this case, the celestial poles) and diverge at the celestial equator. But they are not projections of longitude lines.

For one thing, RA is not measured in degrees — it’s measured in hours. This is based on the fact that the Earth rotates once every 24 hours.

To understand why this is, imagine standing still and staring straight ahead for one hour. At the start of the hour, you’re looking at a specific location in the sky. After exactly one hour, the sky will have rotated by 1 hour of RA, and you will be looking at a spot that’s 1 hour of RA away from the previous spot.

So, there are 24 right ascension lines on the celestial sphere for every hour of Earth’s rotation. Each hour of right ascension is divided into 60 minutes of RA, and those minutes are divided into 60 seconds of RA.

Where is 0h RA, then?

The ecliptic crosses the celestial equator at a point known as the vernal equinox. The RA line that passes through the vernal equinox is 0h RA.

Here, you can see how a star is located using declination and right ascension. You begin at the vernal equinox. You move along the celestial equator by a certain number of hours. Then you move up or down along that line of RA, until you reach the correct line of declination.

Depending on where you are on Earth, you’ll see different parts of the celestial sphere — and different motions of the sky above. There are several markers on the celestial sphere that change depending on the viewer’s location.

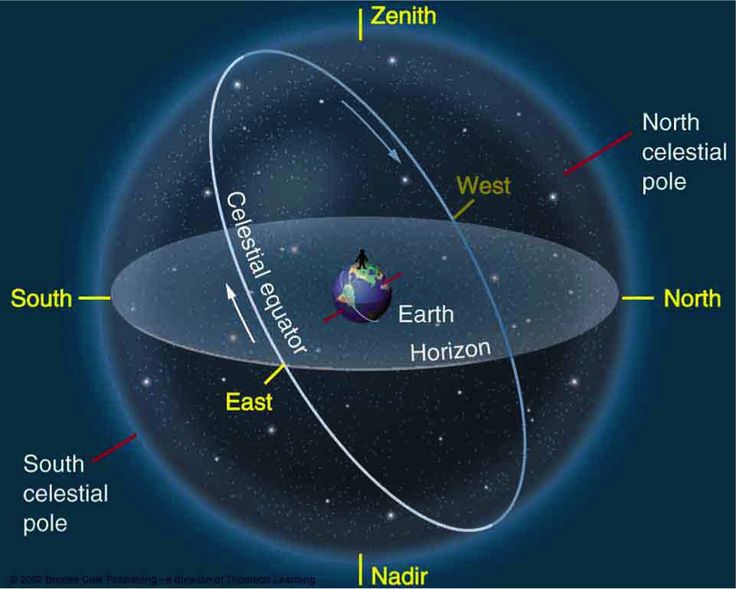

This diagram depicts a specific observer, standing somewhere within North America. I’ll use 32º N latitude for our location, since that’s where I am.

Here, you see a flat plane extending from the Earth to the celestial sphere, representing the viewer’s horizon. From any location on Earth, you can always see exactly half of the celestial sphere, the half above the horizon. (Of course, your particular view may include objects like trees, mountains, and buildings that are in the way.)

The north, south, east, and west “points” — labeled on our horizon — are our cardinal directions. The points on the horizon closest to the north and south celestial poles are the north and south points. Exactly halfway between them are the east and west points.

Also dependent on our location are the zenith and nadir. The zenith is an imaginary point in the sky directly overhead; the nadir is an imaginary point directly under our feet. (You can’t see your own nadir; it’s in the sky but directly on the other side of the Earth from you.)

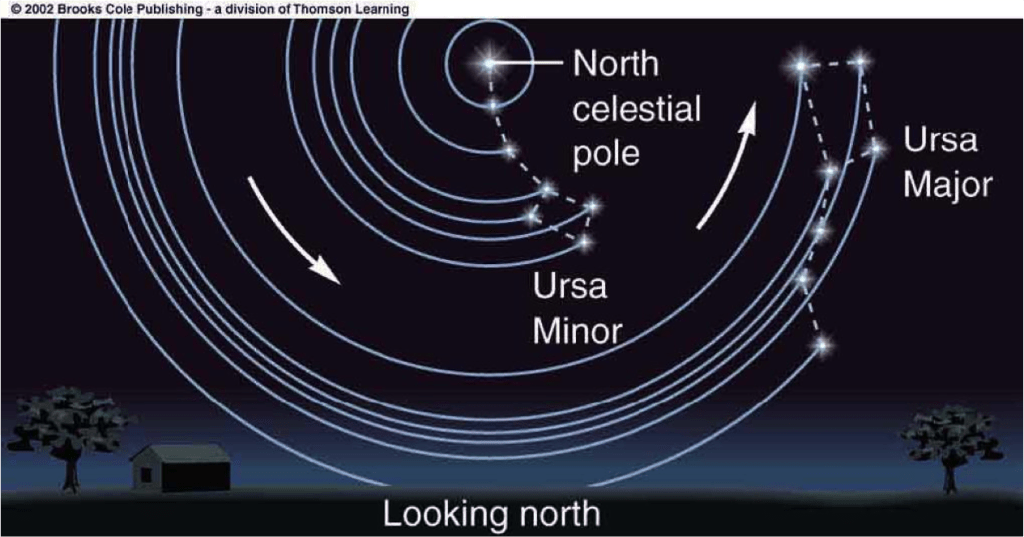

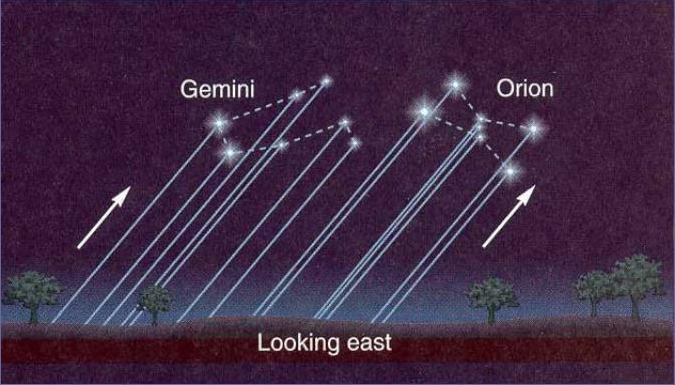

Depending on which direction you look, the motion of the celestial sphere will look a bit different, too.

The closer you live to the poles, the higher they will appear in your sky — and the more constellations will always be visible above your horizon. For example, notice that Ursa Major never dips below the horizon for this observer. That makes Ursa Major a circumpolar constellation, but only for observers living above a certain latitude.

That is to say, if you lived on the equator, you wouldn’t see any circumpolar constellations. The north and south celestial poles would be right on your horizon. Every constellation that rose would eventually set.

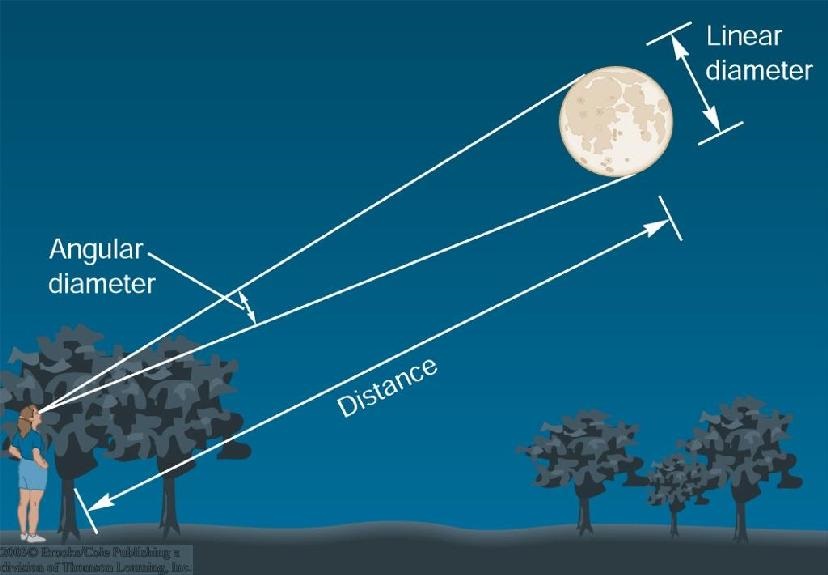

One other way that astronomers use the celestial sphere is for angular distance (and angular diameter).

The distance between or across celestial objects isn’t always easy to find. But one thing is easy to find from our little backwater planet — how big distances or sizes appear to be!

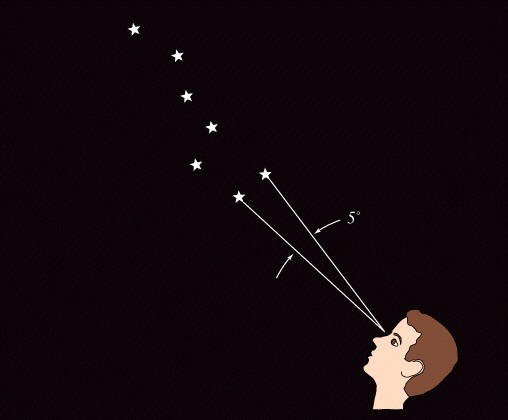

In this case, astronomers use basic trigonometry. An angle is drawn between the two objects, using the observer’s eye as the vertex. Then we measure the angle.

It’s really that simple.

Angles in trigonometry are measured in degrees, arc minutes, and arc seconds. These have nothing to do with units of time. Those same units of angle measurement are used here.

Now that you understand the celestial sphere, we’re ready to explore precession, one of my favorite topics!

Leave a reply to Thomas “Chip” Good Cancel reply