Cosmology is the study of the universe itself: how it came to be, how it has behaved since, and why the laws of physics operate the way they do.

It’s one of the strangest branches of science — second only, I think, to the wacky world of quantum mechanics.

But it’s also fun.

The ideas cosmology proposes can be absolutely mind-bending — and mind-blowing. I find it inspiring. To think that our tiny species — barely ants compared to the broad stretch of deep space, barely a blip in the long stretch of time — can probe this far into the secrets of the universe.

So let’s take the plunge, shall we?

Let’s start by exploring a few basic questions about the universe.

Does the universe have an edge?

The first lesson my textbook tries to teach about cosmology is that the universe does not have an edge.

In fact, my textbook insists that it cannot have an edge: that if it did, that would “defy common sense.”

I have a major problem with that. Astronomy and astrophysics have come a long way since the days of philosophy, when classical thinkers like Aristotle simply reasoned their way to figuring out the laws of nature.

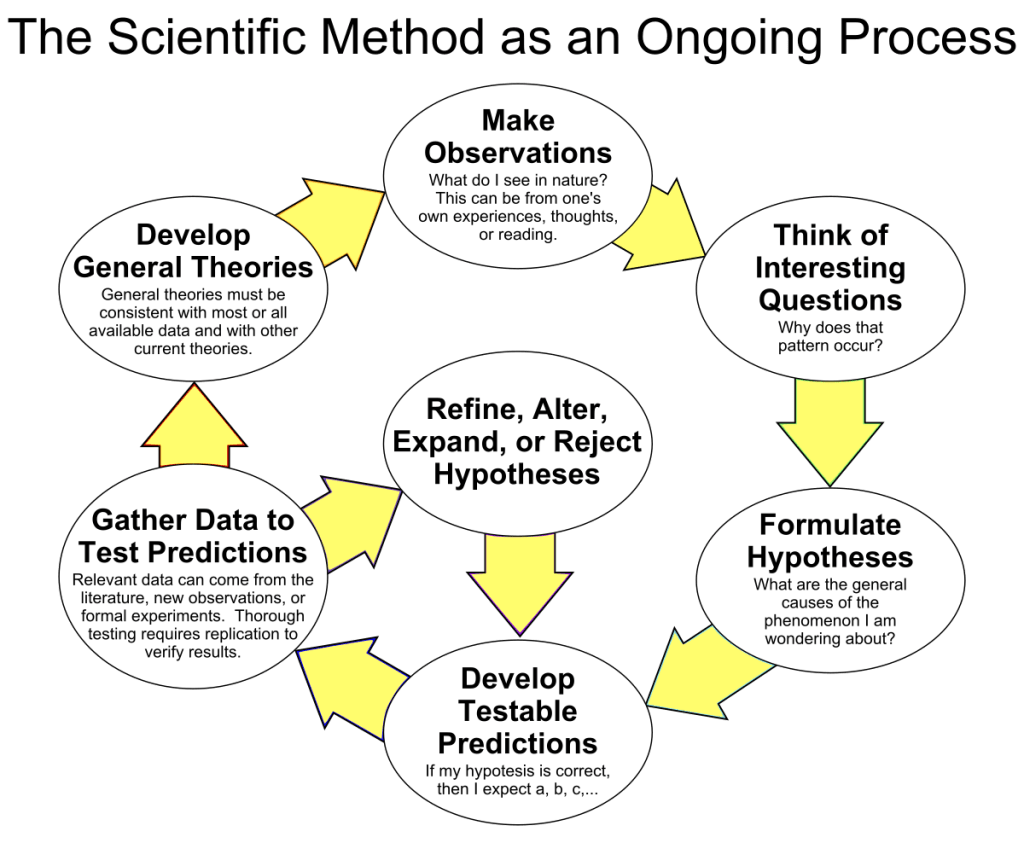

One fundamental fact we have learned since Galileo Galilei’s first experiments with gravity is that human reasoning does not automatically reveal scientific reality. Only the rigor of the scientific method can do that.

Saying that there cannot be an edge to the universe because it defies common sense is not scientific. If there is no edge, that must be proven by experimental means, or deduced by rigorous theoretical calculations.

My textbook, though, takes it a step further:

If the Universe had an edge, imagine going to that edge. What would you find there: A wall of some type? A great empty space? Nothing? Even a child can ask: If there is an edge to the Universe, what’s beyond it?

My reaction to reading this was, “don’t make fun of me for asking a question.”

Never make fun of me for asking a question. This is a perfectly valid scientific inquiry. Science is all about asking questions. Everyone starts somewhere, with questions that may seem silly and basic to more advanced learners. As a science teacher of mine once said, “There are no stupid questions, only stupid answers.”

I have a lot of respect for the writers of my textbook; for years, it’s helped me wrap my mind around complex scientific concepts so that I could explain and teach them myself on this blog. But here, I do believe that the book falls short.

Especially given that, observationally, we do not definitively know if the universe has an edge.

As Astronomy.com puts it, in an article written on August 31, 2023…

Unlike a spherical universe, a flat one can be infinite — or not. And there’s no real way to tell the difference.

That’s because the observable universe — the region we can see — is finite. It does have an edge. There is a horizon beyond which we cannot see. (I’ll explain why that is shortly!)

So, does my textbook have any business discouraging me — or you — from questioning whether the universe has an edge?

However…we might not truly know if the universe has an edge, but there is a general scientific consensus — based on mathematical theory — that it is infinite.

In a later post, we’ll examine how we come to that conclusion.1 But for now, we’ll build our understanding from that assumption. After all, we can always come back and reexamine even our most basic assumptions. The experts do all the time.

Does the universe have a center?

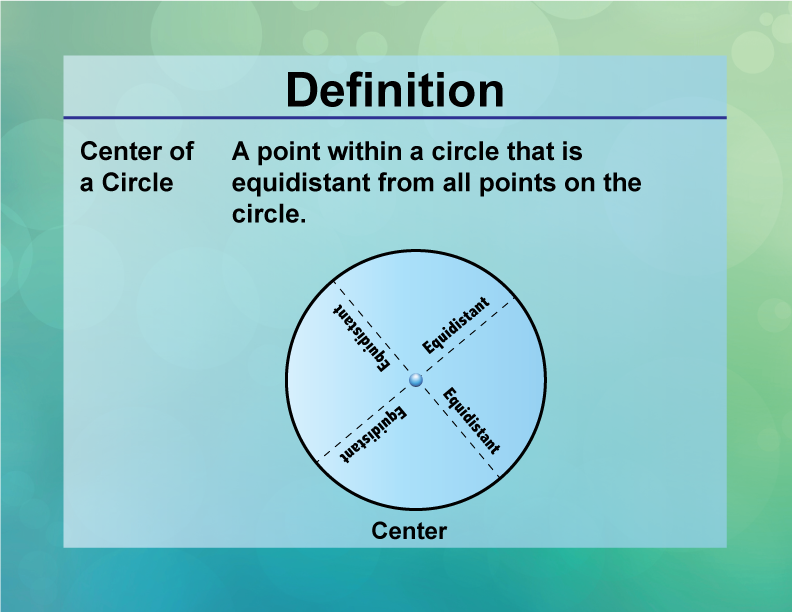

We have accepted — provisionally — that the universe has no edge. And in geometry, centers are defined by referring to edges:

So, we can now accept that the universe has no center.

That leads us to a question you might not expect…

Why does it get dark at night?

Think about it. If the universe is infinite and filled with stars and galaxies, then every line of sight must eventually reach a star — like standing in the midst of a forest.

If you’re standing deep in the middle of a forest, you can’t see out of the forest. Every line of sight meets the trunk of a tree.

Heck, the universe doesn’t even need to be infinite for this to work — no Earth forest is infinite! It just needs to be sufficiently big. But it’s even more true for an infinite universe. There’s no escaping that forest of stars, no possibility of reaching an edge where you see through to open wilderness.

So, if we do indeed live in an infinite universe, it shouldn’t matter that the sun sets. The night sky should glow as bright as the sun, due to the light from countless stars.

This question has become known as Olbers’ paradox, though it’s not really a paradox. It only seemed like a paradox to the scientists of Olbers’ time — the 1800s — because the universe was presumed to be not only infinite in size, but infinite in age.

Olbers’ paradox is easily solved by questioning that basic assumption.

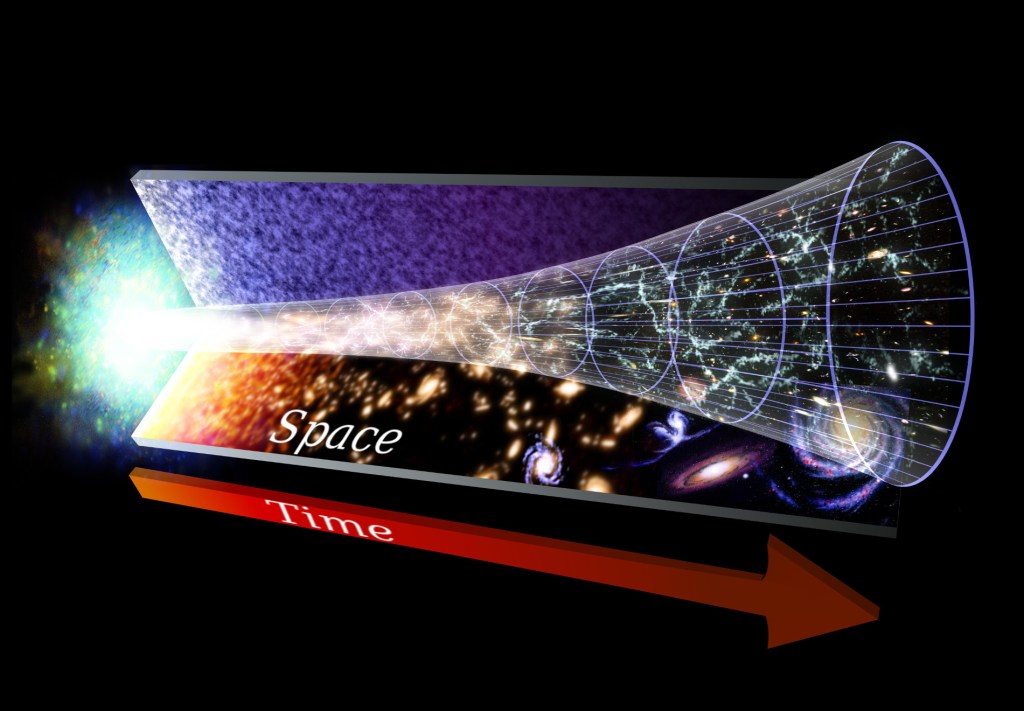

The universe may well be infinite in size, but it had a beginning.

And light takes time to reach our eyes.

Remember what I was saying before about our observable universe being finite? About that horizon beyond which we cannot see?

It gets dark at night because there are distant stars and galaxies whose light has not yet reached us.

Because the universe had a beginning, that light has not had infinite time to reach us. It left its source at a distinct point in time, and it can travel no faster than a certain speed (which happens to be 299,792,458 meters per second).

And that’s why we talk about the observable universe: the limited region of our universe that’s observable from Earth.

Everything astronomers have ever discovered about the universe can be seen within this horizon.

Wait…why do we call it a “horizon?”

Think of what a horizon means in your daily life. It’s the farthest you can see across the surface of the Earth, before Earth’s curvature hides the landscape from view.

Similarly, the universe’s observable horizon is the boundary beyond which the cosmos are hidden from view because light from that distance has not yet reached us.

As a matter of fact, there was another incorrect assumption that the scientists of Olbers’ time made: that the universe is static. That is, “unchanging.”

Is the universe changing?

In fact, the universe is not static: it is expanding.

Since the beginning, space itself has been stretching like a rubber sheet. The distances between physical objects have expanded.

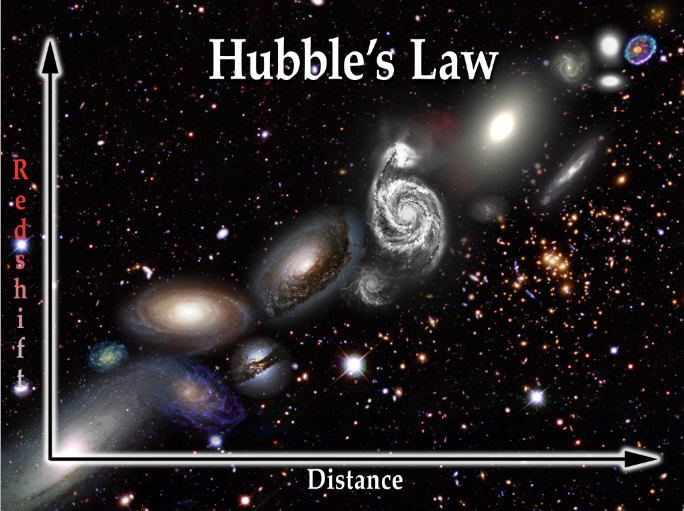

I first teased this idea back in our discussion of the distances to galaxies — when we explored the Hubble Law.

Hubble discovered that you could estimate the distance to a galaxy by calculating its redshift.

The idea of redshift is familiar from the Doppler effect: we use objects’ spectra to determine how fast they’re moving toward or away from us. But the redshifts of distant galaxies seemed to pose a problem. They seemed to imply that galaxies were receding from us faster than the speed of light.

That’s not possible. The speed of light is often called the “universal speed limit.” Nothing can go faster.

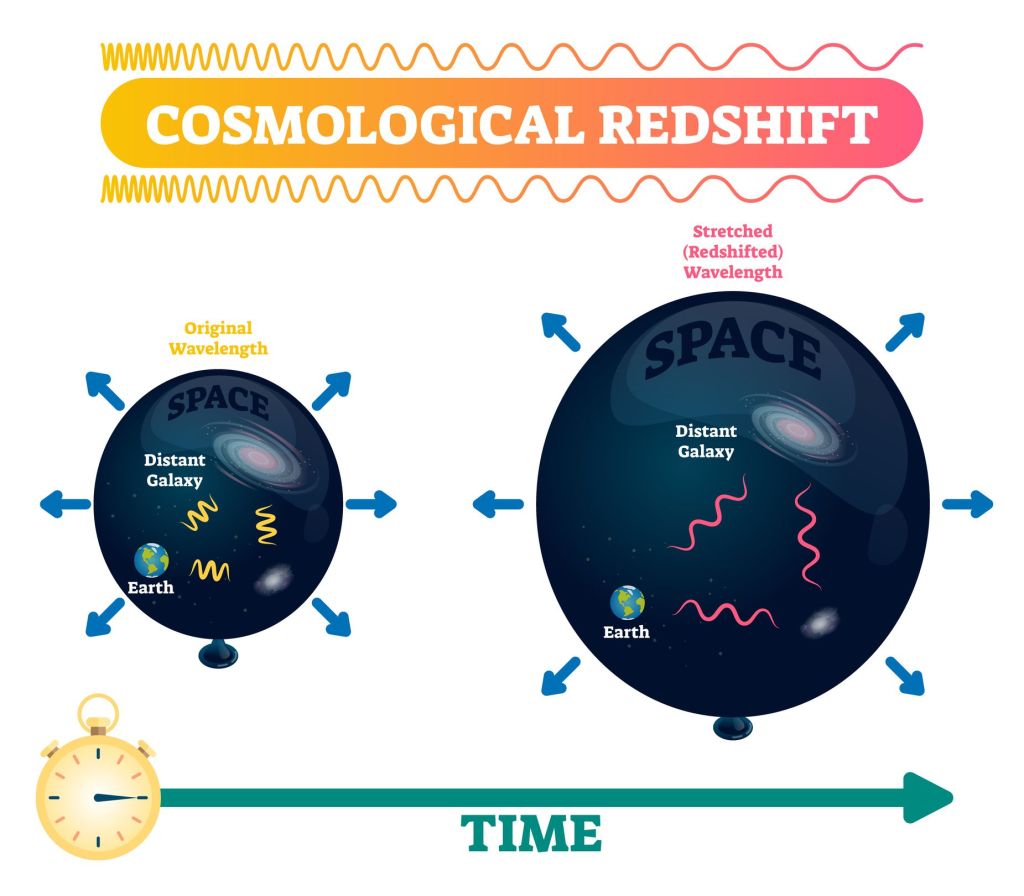

But astronomers later discovered that these redshifts were not due to the Doppler effect. They were an effect of space itself expanding, stretching the traveling light waves into longer, redder wavelengths.

This type of redshift became known as cosmological redshift.

But let’s not get so bogged down in the details of redshift and receding galaxies that we forget the discovery we just made.

The universe had a beginning…and it’s been expanding ever since.

It’s still expanding.

From our Earthly vantage point, all distant galaxies appear to recede from us — and the farther away they are, the faster they appear to recede.

In fact, it looks almost as if Earth lies at the universe’s center, with all of space expanding away from us.

But this is an illusion.

Remember that, as far as we know, the universe has no center and no edge. No one location in the universe has a special viewpoint. The space itself between all galaxies is stretching.

To visualize this, astronomers often use a raisin bread analogy…

This analogy isn’t perfect — the bread definitely has an edge! But, in general, we can think of the raisins as being like galaxies, and the bread as being like space itself.

As the dough rises, the raisins are carried apart from one another. Two raisins that started out close together will be pushed apart slowly, but raisins that started out farther apart have a lot more dough between them. All that expanding dough carries them apart from one another faster.

As my textbook puts it, “bacterial astronomers” living on each raisin would observe the same redshifts and derive the same Hubble law, regardless of which raisin they lived on. They would each observe the bread appear to expand away from them.

And the same goes for galaxies in the universe.

It’s important to clarify that galaxies themselves are not moving. As you saw with the raisin bread, the “fabric” of space itself is expanding between them, carrying them away from one another.

But all this leads to another question…

If the universe is expanding, then how did it start out? It must have been smaller, in its earliest days — but what was that beginning actually like?

Next up, we’ll take a dive into something you’ve probably heard of: the Big Bang.

- My own understanding of cosmology has improved since writing this post; I’ve updated this to reflect greater confidence in the universe’s lack of an edge. (On principle, I still disapprove of my textbook discouraging questions on the matter.) ↩︎

Did I blow your mind? 😉