The universe as we know it was born out of chaos.

We have a pretty good idea of the scale of our universe and how it began—as an infinitely dense point of matter that blew apart in what we call the Big Bang. That’s chaos for you, right there.

And chaos continues to define our daily lives.

Stars are born out of the complete chaos of gravity, and nothing in the universe forms gently. Our moon was born out of a violent collision with the Earth. And I’m sure you’ve noticed how easy it is to let a room get disorganized.

All these are examples of chaos—known as entropy in science. Everything tends toward chaos. But the ancient Greeks rebelled against this idea.

In their view, everything in the cosmos had to be perfect. It was a somewhat spiritual way of looking at the universe, if you think about it. And even as they developed the groundwork for science as we know it today, one idea hindered them…

This idea was the concept of uniform circular motion.

It’s ironic, how the Greeks pictured the universe as a spiritual place of perfection. Their attempts to understand their world in a nearly scientific way actually leaned towards imagining the supernatural.

But we can thank them for developing the foundation of the scientific method.

The Greeks had no idea where they stood in the universe. To them, the Earth sat below a canvas of pinpricks of light that moved in circles around the mysterious north pole. It’s no wonder “true north” and the north star were considered so special!

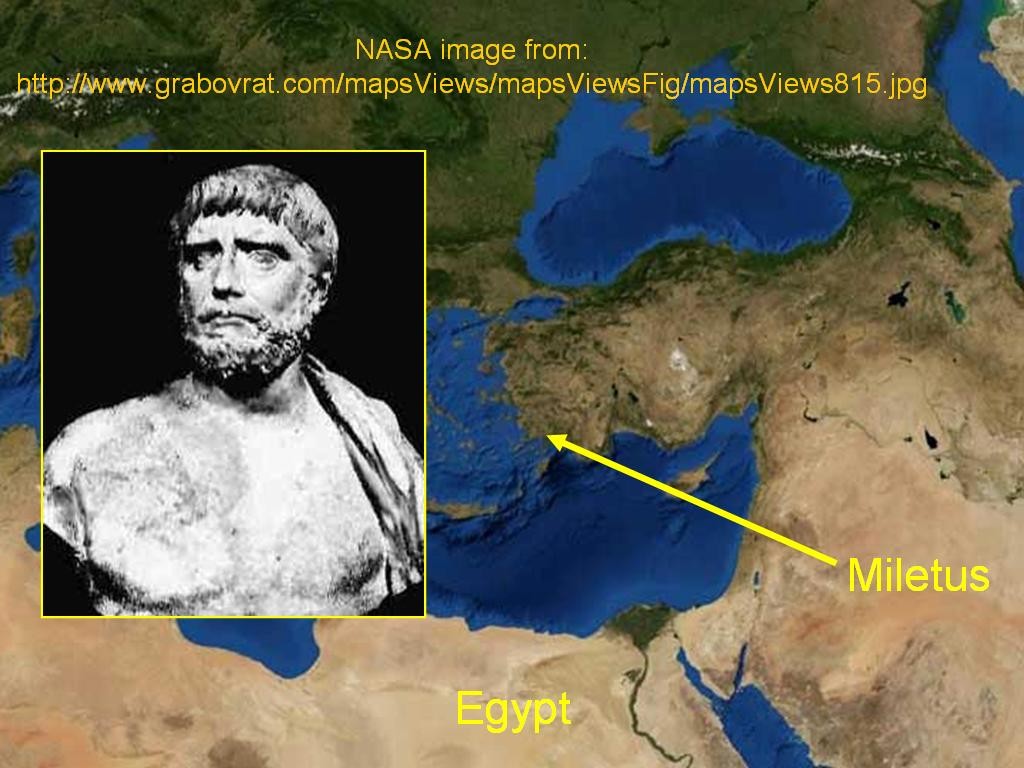

The sky above may have baffled the Greeks, but they certainly didn’t let that stop them. Thales of Miletus was the first to believe that, contrary to the teachings of earlier cultures, the universe was rational and could be understood.

Thales was, first and foremost, a philosopher, and the astronomy of his time—624-547 BCE—was a philosophy. He heralded the beginning of Greek philosophy, mathematics, and other directions of learning.

He held that the mysteries of the universe were only mysteries because they were unknown. They weren’t unknowable. Thanks to this view, many other Greek philosophers rose to prominence in his wake and did their best to understand the heavens.

Around the middle of Thales’ life came Pythagoras, who lived from 570-500 BCE. You might have heard of Pythagoras—he’s the one who came up with the Pythagorean theorem.

And of course, I’d be remiss if I didn’t include something about his famous theorem…

Ok, I’ve gotta hand it to Pythagoras. The math isn’t that complicated. But to figure out a formula that works for only one type of triangle? Think about it. That 90° angle could be anything from 1° to 179° and still make a triangle. And he figured out that 90° angles were special?

Alright, so 90° angles aren’t that special. The Pythagorean theorem is actually part of a formula that works for every triangle, but it’s simplified because some of the math isn’t needed…

Okay, okay, I hear you. I’ll stop blathering on about math and get back to the science.

For the record, though, Pythagoras’ contributions to math are actually important to his contributions to science. Like Thales, he suggested that the universe could be understood by the human mind. But he also added that the universe behaved musically.

What the heck does that mean?

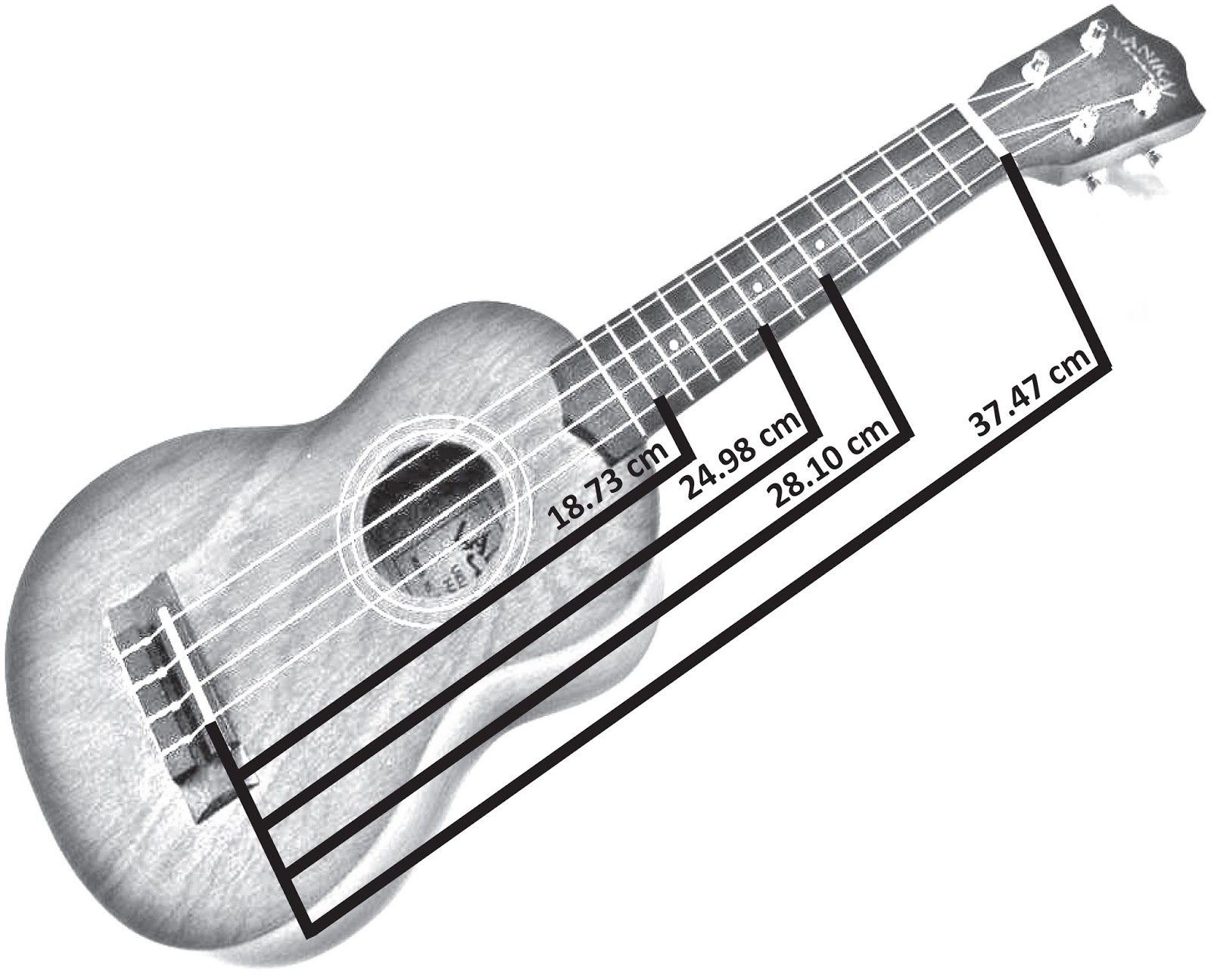

Well…Pythagoras recognized that math was present in music. The strings on any stringed instrument play different pitched sounds when made to be certain lengths.

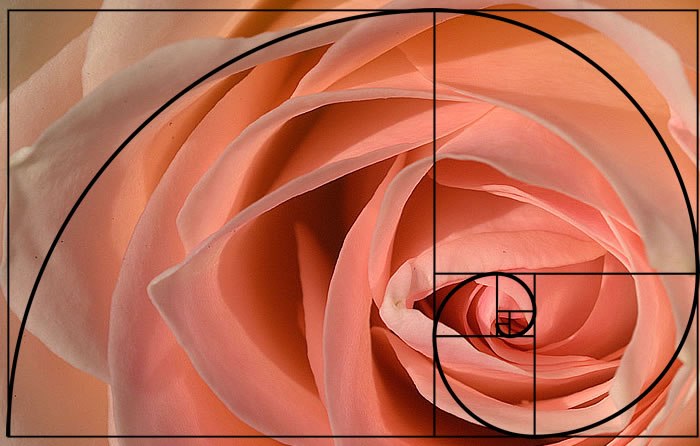

And he also noticed that math was present in nature—all around us, in fact. I’m not sure who first came up with the golden ratio, but Pythagoras was aware of it.

Here’s just one example of the golden ratio in nature. I’m not going to explain the golden ratio, but it follows certain rules in math and always comes out the same. And look how well the petals of this flower mimic the curves it forms.

Flowers aren’t the only things in nature that show a connection to mathematics, and Pythagoras saw that. He’s even quoted as saying that the universe plays music, we just don’t have ears that can hear it—of course because music and math are related.

It’s funny how close to the truth Pythagoras was.

No, the universe doesn’t actually play musical tunes, at least not like we would recognize on Earth. But there are sounds you can pick up from space, and guess what sounds are? Music, without the same clear and organized quality we’re used to.

Sound, in fact, is just another form of chaos in space. Music is perfection—it’s why it takes so much practice to play well. No wonder Pythagoras was attracted to the idea of a connection between music and the universe.

In trying to understand the universe, a few other philosophers stepped up to the plate and suggested explanations. Anaximander, who lived from 611-546 BCE, suggested that the world was made of wheels and fire.

I know. The wheel is one of our most basic inventions; you can even see how it appeals to the ancient Greek idea of perfection. But fire? Perfect? I can’t quite see it.

Anyhow, here’s Anaximander’s model of the universe:

Anaximander’s idea was that the Earth was a cylinder sitting amid several wheels, and outside the wheels was fire. That explained the sun, stars, and basically everything else in the sky, since everything looked like stars. All those little pinpricks of light in the sky were just holes in the wheel, through which the fire could be seen.

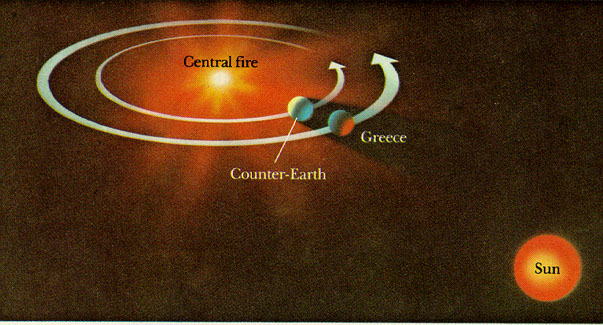

Philolaus, a Greek philosopher who lived in the fifth century BCE, had another idea. He was actually the first to suggest that the Earth moved, though he was hardly even paid any mind at the time.

Philolaus said that the Earth moved in a circular path around a central fire, which wasn’t the sun. He said we can’t see the fire because there’s a “counter-Earth” between it and us. The sun is somewhere outside this whole system.

And then, of course, there was Plato.

I’ll bet you recognize his name, even if you’re not familiar with his role in Greek and astronomical history. Plato, revered as he was, can actually be credited with taking astronomy one step forward and two steps backward.

Why? Because he had the fantastic idea that human observations are distorted and misleading, and only pure thought can lead to true conclusions.

Why was this detrimental? Because all we know of the natural world today is based on observations. The entire scientific method arose from observing the world around us. And astronomy is especially dependent on observations.

We can’t touch most of the cosmos, so without observations, astronomy would be absolutely nothing.

Yet, Plato suggested that human observations won’t actually lead us any closer to the truth. His idea actually makes sense for his time—he noticed the chaos of our world, and decided that for the universe to be perfect, what we see of it must only be a distorted shadow.

Uniform circular motion was Plato’s idea. It was the idea that the most perfect shape in nature is the sphere, so naturally the heavens must be made up of spheres. And it was an idea that would continue to plague Greek astronomy for some time.