If you’ve been following my recent posts, cosmological redshift will likely be a familiar idea. I introduced it in my post on the Hubble Law. We revisited it again in our discussion of the size and brightness of galaxies.

When we explored active galaxies, we encountered it again in tracing the full story of galactic evolution.

But truly, this topic is most at home in discussions of cosmology, and sure enough, we’ve seen it again and again in this unit: in our intro to cosmology, or exploration of the Big Bang, and finally, our dive into the discovery of the CMB.

If you’re a little confused about what exactly cosmological redshift is, this post is for you…

What is it?

In short, cosmological redshift is a stretching of the wavelength of light.

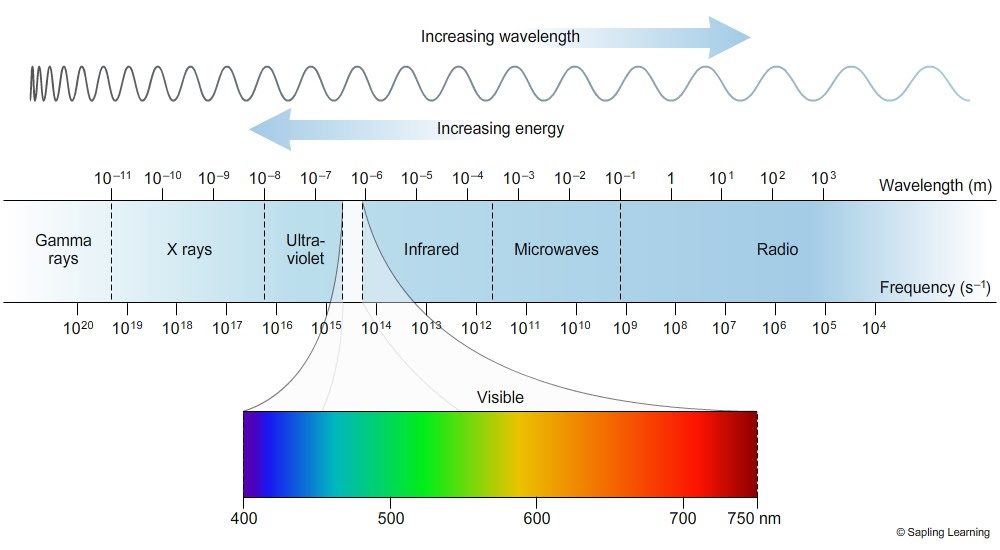

And by “light,” I mean any part of the electromagnetic spectrum:

The electromagnetic spectrum (or EM spectrum) is the spectrum of all electromagnetic radiation in the universe. And it is one of astronomers’ most powerful tools for understanding the universe.

Here’s what’s important to us: different “types” of light are distinguished by their wavelength. That is the distance between two similar points on the wave: for example, from peak to peak or from trough to trough.

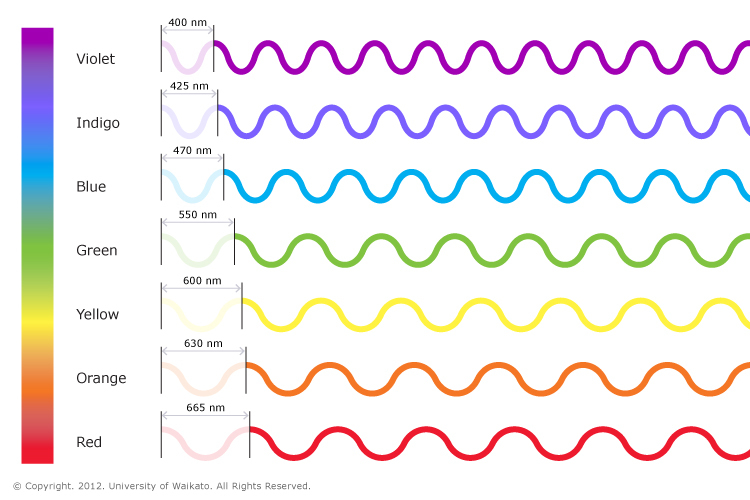

The graphic below shows how the different colors of visible light differ by wavelength:

Note that blue/violet have the shortest wavelengths, and red has the longest wavelength.

Now, let’s say a particular photon (a particle of light) has a certain wavelength — say, 470 nm — when it is emitted from a source object.

If something stretches that photon’s wavelength, it will appear redder, because red has a longer wavelength.

This goes for types of radiation other than visible light, too. Gamma rays have the shortest wavelengths of any other electromagnetic radiation. If those photons are stretched, they could appear as x-rays, visible light, infrared, or even radio waves — depending on how much they are stretched.

Is it a Doppler shift?

The short answer is: no.

Here’s why:

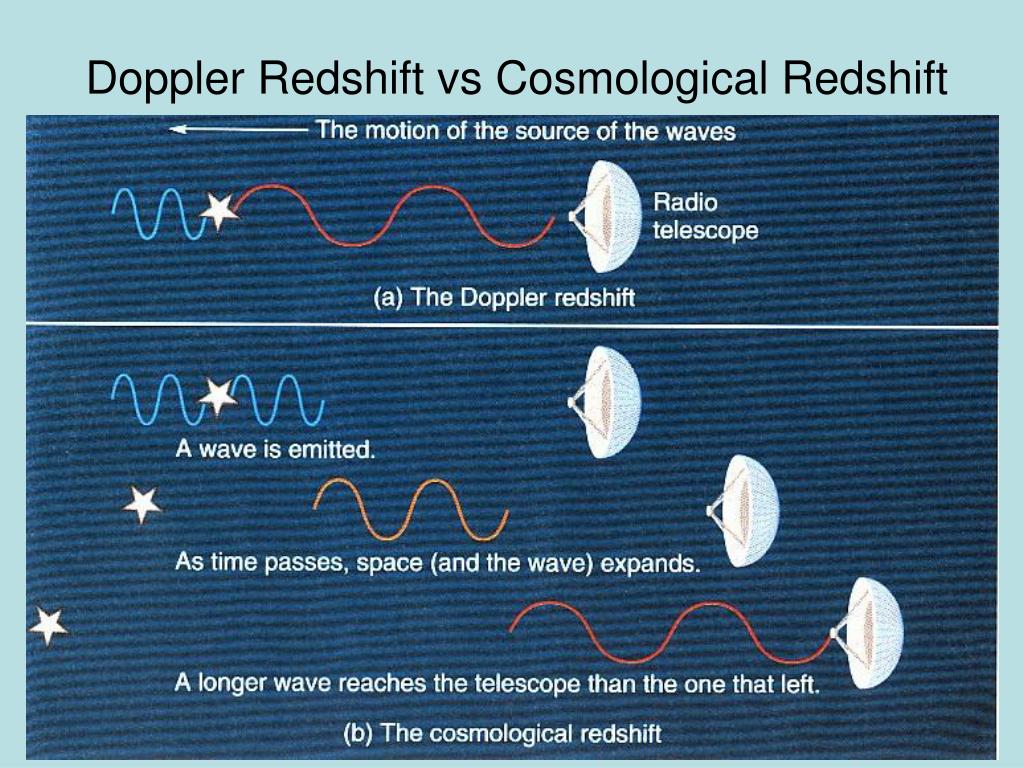

Doppler shifts are a related phenomenon. The Doppler effect can also produce a type of redshift, but not a cosmological redshift.

The Doppler effect produces both redshifts and blueshifts, depending on the direction in which the source object is moving.

For example, if a star moves toward an observer, the wavelengths of its light will seem to shorten (toward bluer wavelengths). This is a blueshift.

Note something important: The star will not appear blue just because it is blueshifted. The blueshift will be apparent only in its spectrum (which is another discussion entirely; you can find a post all about it here).

How does cosmological redshift work, then?

How does it work?

One of the most important distinctions between Doppler shifts and cosmological redshift is that you will never see a cosmological blueshift.

That’s because Doppler shifts are due to the actual motion of source objects through space. Cosmological redshift, on the other hand, is due to space itself expanding.

Albert Einstein discovered in 1916 that the fabric of space itself is expanding, a bit like stretching rubber — something that we’ll explore very soon!

As space expands, a traveling photon will get stretched to longer and longer wavelengths.

You can think of this as kind of like straddling a ravine…

Imagine that these two cliff faces are drawing farther and farther apart. The ravine between them is getting wider and wider — that is, expanding.

Those two cliffs are two locations in space. And the poor guy hanging between them is a traveling photon of light.

Unlike an actual person, light has the luxury to simply stretch to a longer wavelength — so it can still reach from one cliff to the other and hang onto both cliff faces. But it will be redshifted. Because it has a longer wavelength, it appears redder.

Now, here’s the key:

In space, the “cliff faces” — that is, for instance, a pair of galaxies — are not moving. It is the “ravine” — the space between them — that is expanding and carrying them apart from one another.

That is the difference between cosmological redshift and Doppler shifts. Doppler shifts represent the actual movement of objects in space (and thus can be redshifts or blueshifts). But cosmological redshift results from the expansion of space itself.

There is only cosmological redshift, not cosmological blueshift, because space is only expanding. It is not currently contracting: that is, the space between objects is not shrinking, carrying galaxies closer together. So we do not observe shortening of wavelengths.

Why is it so important?

First: It helps us measure the distances to galaxies.

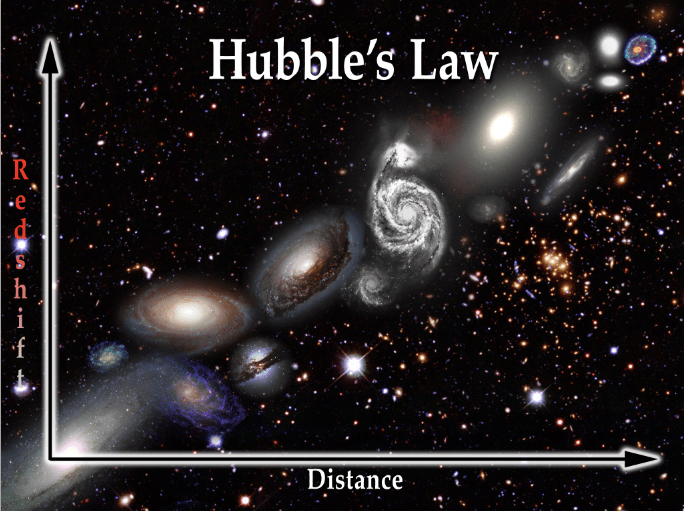

That’s because cosmological redshift is directly related to distance. This is called the Hubble Law.

Two galaxies that are far apart have more space expanding between them, so the wavelengths of the photons they emit will be stretched more.

On the other hand, two galaxies that are relatively close together have less space expanding between them, so the wavelengths of the photons they emit won’t be stretched quite as much.

So, to us Earthlings, very distant galaxies will appear redder, and nearer galaxies will not have been redshifted nearly so much — they will appear close to their true color.

And that, by the way, brings me to a minor difference between cosmological redshift and Doppler shifts: while Doppler shifts only reflect in spectra, cosmological redshift actually changes the observed color of a distant object.

This little red blob is a distant galaxy, one of the farthest we are currently able to detect. It’s not really red: the light we observe left that galaxy as higher-energy, shorter-wavelength photons. But by the time that light reached observers on Earth, it had been redshifted quite a bit.

The direct relationship between cosmological redshift and distance was the first evidence that galaxies are receding from each other, carried apart by the expanding space between them.

And this is the second reason why it’s so important.

That relationship — the Hubble Law — is strong evidence in favor of cosmologists’ current understanding of how the universe began and how it is evolving. It’s one of the bedrock pieces of evidence supporting current cosmological theories.

I hope I’ve managed to clarify cosmological redshift a bit! Next up, we’ll explore one of cosmology’s most mind-bending concepts: the shape of space itself.

Leave a reply to disperser Cancel reply