At first glance, this is an ordinary image of a galaxy cluster: specifically, Abell 1689.

If we look closer, though, we see that there’s something weird going on with the more distant, background galaxies in the image.

Many of those distant galaxies appear elongated and stretched into thin arcs around the foreground cluster.

We’ve seen this effect before — and its name is gravitational lensing.

It’s compelling evidence for the existence of the mysterious dark matter. And now, it’s going to help us figure out the total density of the universe.

Did that last sentence blow anyone else’s mind, or was it just me?

Anyway…let’s get to it.

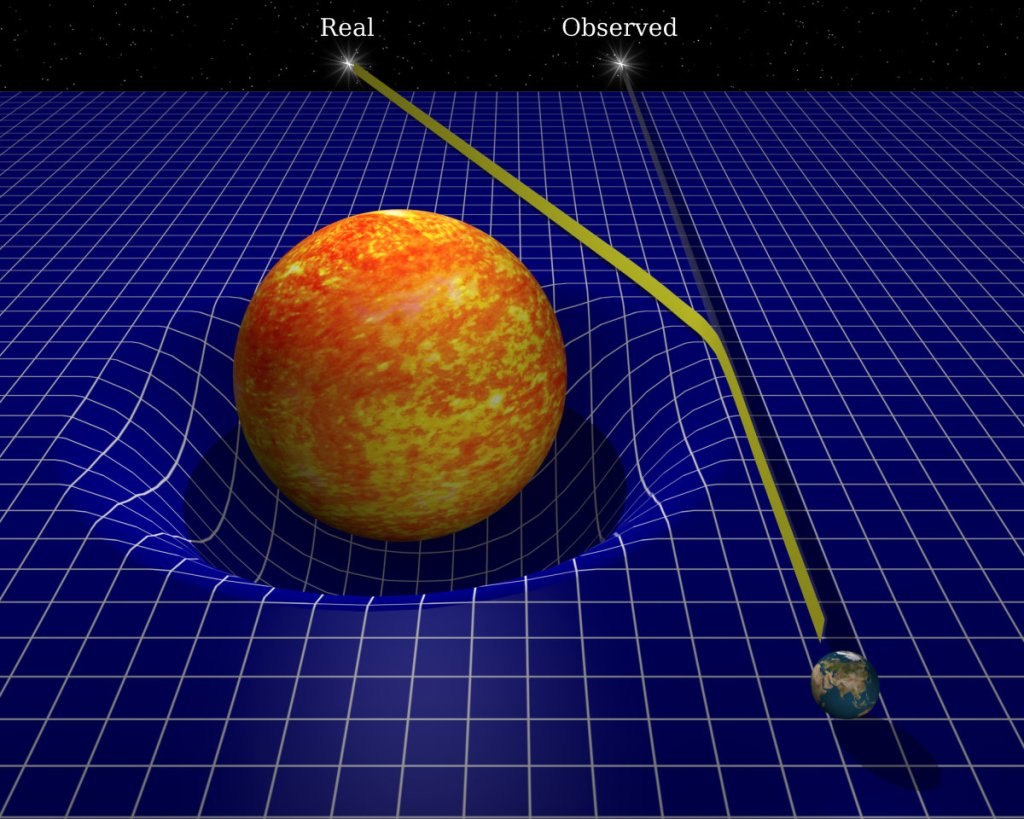

Gravitational lensing occurs when the path of light is deflected around a gravitational field:

We see this during total solar eclipses. When the moon eclipses the sun, blocking out the majority of its light, we’re able to see stars right near the sun.

If we take a photograph of the stars around the sun then, and compare it to one taken of the same stars at night, we see that the positions of the stars appear to shift a bit.

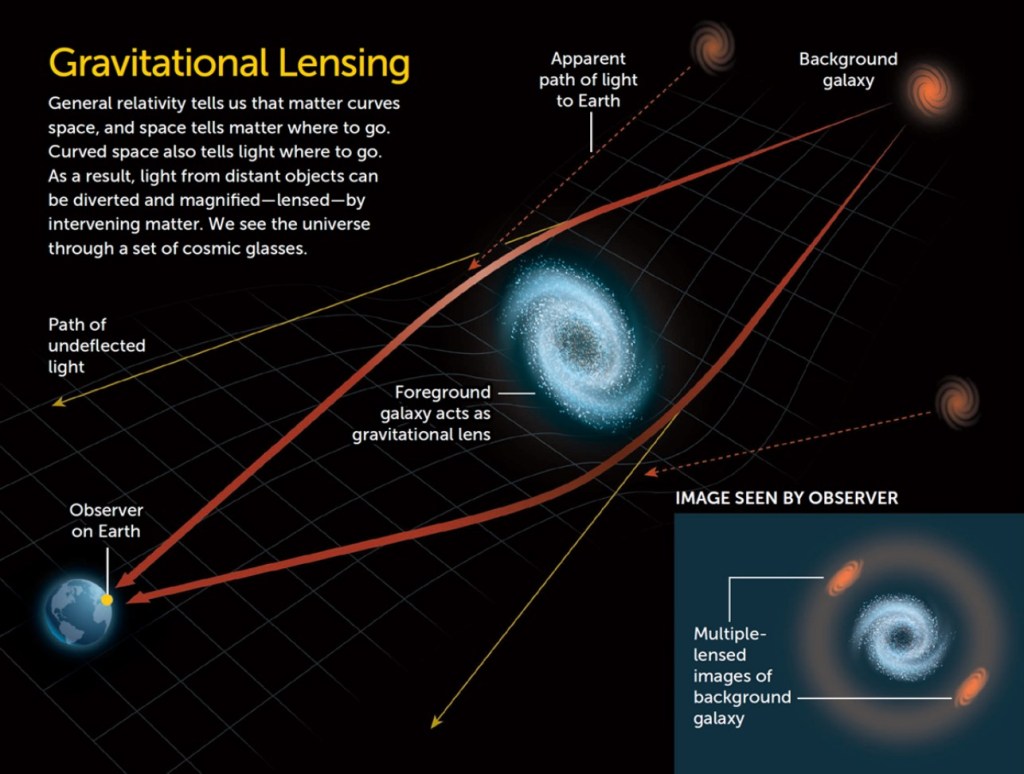

The same thing can happen in deep space, too.

A massive, relatively nearby object (a foreground object) can deflect the light of a more distant object (a background object) so that it appears in a different position, or even appears “doubled.”

The effect is the most pronounced, though, if we’re dealing with a super massive foreground object — like a cluster of multiple galaxies.

The distant galaxy might be mirrored several times over, stretched into long arcs, or otherwise distorted.

That’s how we get absolutely ridiculous examples of gravitational lensing, like this:

I assure you…that middle galaxy isn’t really shaped like a long, narrow squiggle.

Anyway.

Using the light from the observed galaxies in the foreground cluster, we can estimate how much mass the cluster must have. And that’s when things get weird.

It’s not nearly enough to produce the pronounced lensing effect we’re seeing.

This isn’t what gave rise to the idea of dark matter — galaxy rotation curves did that — but it’s strong evidence that dark matter really does exist.

Using observations of both the observed matter present and the amount of gravitational lensing present in galaxy clusters, we estimate that dark matter outweighs “ordinary” matter by a factor of between 5 and 10…

…which is a bit mind-blowing, to say the least. My textbook describes looking at the visible matter in galaxies as like looking at a tree and seeing only the leaves.

Okay, so we know roughly how much more dark matter there is than ordinary matter. But how much ordinary matter is there?

To find this, we can look to the conditions of the universe in the first few minutes of time.

The early universe was like the core of a star: insanely dense, insanely hot, and insanely chaotic. These are exactly the right conditions for nuclear fusion.

That’s how the first atomic nuclei were produced. Protons smashed together to create deuterium, a heavy form of hydrogen. Deuterium smashed together to create helium-3, a light helium nucleus.

Helium-3 smashed together with deuterium to create helium-4, which has an atomic weight of 4…and that’s where we run into a problem.

Element building in the early universe had to proceed step-by-step, adding one particle to a nucleus at a time. But there are no stable nuclei with atomic weights 5 or 8.

This was a problem for element building in the early universe. But for us, it’s a very important clue to the density of that early universe.

See, if the universe had a high enough density, it would have had a high pressure and the existing atomic nuclei would have been crashing into each other a lot. Smashing together more nuclei to create the next stable nucleus — lithium-6 — wouldn’t have been a problem.

The early universe was dense enough to create some lithium-6 and move on to lithium-7 — but it stopped there. It couldn’t jump over step #8 and create a berylium-9 nucleus.

Lithium-7 was a dead-end for the early universe. And for us, it works like a fossil — a window into those early conditions. A moment frozen in time.

If we can measure how much lithium-7 was actually produced, it places an upper limit on the density of the universe. It can’t be so dense that we would expect to see more abundant lithium-7 than we actually do.

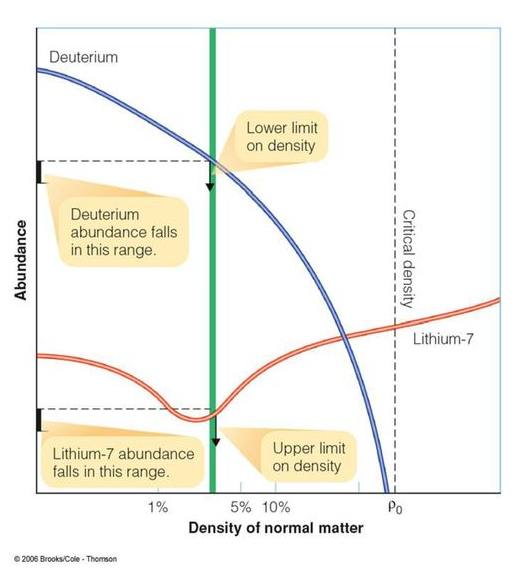

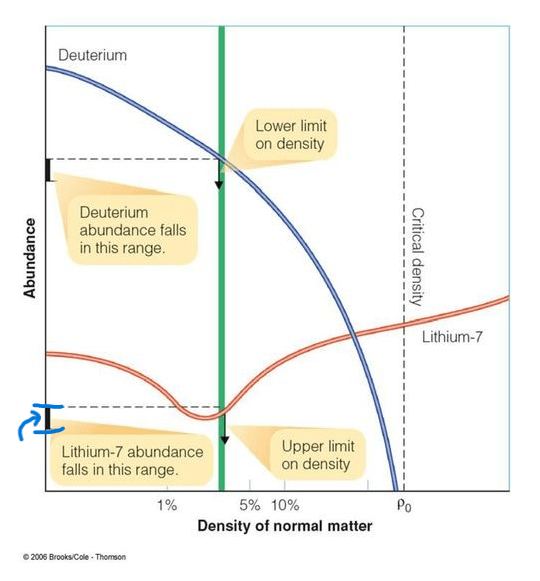

This graph contains a lot of important information, so let’s break it down.

On the horizontal axis, we see the density of normal matter — that is, ordinary matter, not dark matter. It’s written as a percentage of the critical density: 9 x 10-27 kg/m3. This is the density that the universe would have if space-time were exactly flat.

This graph uses the abundance of deuterium and lithium to determine what the overall density of ordinary matter must be. We can compare that to the critical density to discover what curvature the universe must have.

The orange line shows the abundance of lithium-7 we would expect to see depending on the density of ordinary matter, and the blue line shows the same for deuterium.

Now, look at the vertical axis. See the shaded range at the bottom?

That’s the observed abundance of lithium-7. It’s a range of values rather than a single value because any scientific observation comes with error margins.

That range shows us the upper limit of the density of ordinary matter: the rightmost edge of that green band. See how, after the green band, the lithium-7 line arches up and away? If the universe were any denser, then more lithium-7 than we observe would have been produced.

You’d think that lithium-7 would also give us a lower limit, because the universe had to be dense enough to “jump over” step #5 in nucleosynthesis…

…but deuterium just so happens to restrict that lower limit even further, to the leftmost edge of that green band.

We’re left with a very narrow range of possible densities — just between 4% and 5% the critical density. But remember, we’re missing dark matter.

If we add in 5 to 10 times as much dark matter as ordinary matter, we get a denser universe. But it’s still less than 50% the critical density.

If we’ve correctly measured the abundances of ordinary matter and dark matter, then the density of the universe isn’t even close to the critical density — that is, it’s not nearly dense enough to be flat. This would seem to indicate that the universe must be negatively curved, like a saddle.

…unless gravity isn’t the only thing that determines the shape of space.

But that’s spoilers! We’ll get to that very soon — but first, we’ll take a closer look at the role of dark matter in the universe.

Did I blow your mind? 😉