In 1998, astronomers made an extraordinary discovery.

Contrary to expectation, the expansion of the universe is accelerating.

Astronomers wondered at first if their measurements were wrong; further measurements confirmed the results. And then confirmation of the expansion came in the form of the Two-Degree-Field Redshift Survey, a survey of 250,000 galaxies and 30,000 quasars.

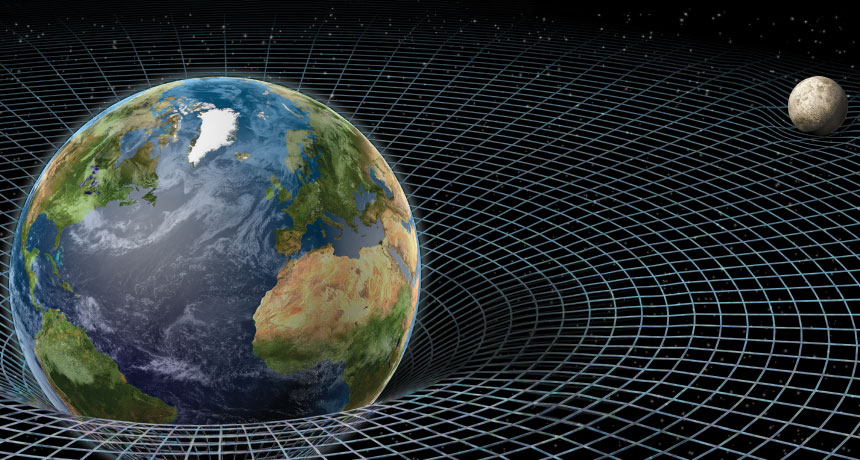

The theory of general relativity holds that gravity — which works by curving space-time — should slow the universe’s expansion. There must be some mysterious force that can counteract gravity.

But what is it?

Einstein himself suggested a possibility in 1916, only a year after he published his theory of general relativity.

Let’s consider the universe as scientists understood it at the time: a universe ruled only by the domineering force of gravity.

Einstein recognized that his theory wouldn’t allow for a static (unchanging) universe. His theory predicted that gravity determines the shape of the universe — because it works by literally bending space-time.

That means that gravity must also be able to contract space-time. With nothing to stop it, it would carry galaxies closer to one another.

On the other hand, the strength of gravity decreases with distance. Perhaps galaxies were flying apart from one another so rapidly that the gravitation between them was too weak to pull them together.

In 1916, the expansion of the universe hadn’t been discovered yet. For all Einstein knew, the universe was static. So he added a constant to his equations that you may have heard of before: the cosmological constant, lambda (Λ).

Lambda is, in essence, a repulsive force that balances gravity. It makes it so the universe won’t expand or contract.

In 1929, though, Edwin Hubble helped settle the debate over how far away galaxies were — and in the process, discovered that the universe was, in fact, expanding.

Einstein then famously called the cosmological constant “fudge factor” the biggest blunder of his career.

Astronomers would spend the following decades trying to detect a slowing of the universe’s expansion, assuming that there was no cosmological constant to prevent it. Finally, in 1998, the newly launched Hubble Space Telescope enabled observations of distant galaxies with unprecedented accuracy.

That was when astronomers discovered that the expansion wasn’t slowing down — it was accelerating.

Suddenly, the general relativity equations needed some kind of force to counteract gravity.

Enter, stage left: dark energy.

Dark energy is a catch-all, placeholder term for whatever is driving the acceleration. And the leading possibility brings us right back to the cosmological constant: an antigravity force originating from “empty” space.

This is because, according to the whacky world of quantum mechanics, true “empty” space doesn’t exist. There’s no such thing as “nothing.” There’s always something there.

That “something” comes in the form of matter-antimatter particle pairs that appear, annihilate one another, and blip out of existence as quickly as they came.

But particles are matter, and matter can’t just “disappear.”

The annihilation produces two gamma rays — high-energy electromagnetic radiation.

That’s E=mc2, by the way. Matter converted to energy. (We’ve seen this before, in our foray into the first moments after the Big Bang.)

This energy — produced by the annihilation of matter-antimatter pairs — is termed vacuum energy.

In the years that the cosmological constant was assumed to be a blunder, it had been linked to the idea of vacuum energy. Physicists suggested that vacuum energy was, in fact, Einstein’s cosmological constant.

But there’s a problem: it doesn’t explain all observations.

Enter, stage right: quintessence.

Quintessence is an alternative hypothesis to the cosmological constant. And quite frankly…it’s bizarre.

The ins and outs are beyond me at this point in my education, so I’m not going to try to paraphrase it. Here’s how the Scientific American describes it:

Quintessence would be some form of energy throughout space with a negative pressure. In contrast to the cosmological constant, quintessence could change over time. One version of quintessence, called phantom energy, postulates an energy whose density increases with the age of the universe, leading to an ultimate “big rip” when space is torn apart by runaway expansion until the distance between particles becomes infinite.

And again, we run into a problem.

Quintessence doesn’t explain all observations, either.

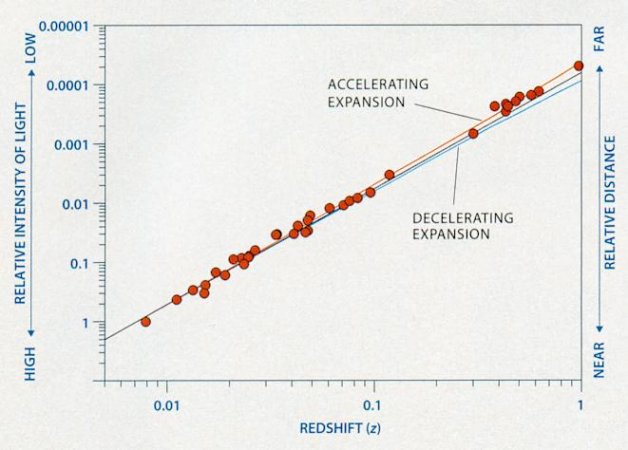

At the end of the day, the fact is that we just don’t know what dark energy is yet. All we know — thanks to data from distant type 1a supernovae and the Two-Degree-Field Redshift Survey — is that the universe’s expansion is, in fact, somehow accelerating.

These supernovae are slightly fainter than expected given their redshifts, which means they are a bit farther away than the Hubble Law says they are. Meaning, expanding space time has carried them away from us faster than the Hubble Law predicts.

In other words, the supernovae’s increasing distance has outpaced the Hubble Law. That can only mean that the expansion of space is accelerating.

But when we observe even more distant type 1a supernovae — as far away as 12 billion light-years — we see something odd.

These more distant supernovae are brighter than expected. And that means they must be closer than the Hubble Law predicts.

How do we explain that?

Apparently, there was a time about 12 billion years ago when the universe’s expansion was not accelerating; in fact, it was slowing down. And that makes a surprising amount of sense. In fact, it confirms a theoretical prediction about dark energy.

12 billion years ago — roughly 2 billion years after the Big Bang — the universe had long since entered the age of stars and galaxies. And that means there was plenty of gravitation going on. After all, gravity is what holds galaxies together.

But the universe was also young, and had not yet expanded much. Galaxies were much closer together.

And that means that gravity could dominate.

Since gravity was stronger than whatever force gave rise to dark energy, the expansion slowed. But it only slowed. It didn’t stop. The expansion continued.

Remember what we were saying before, about gravity decreasing with distance?

Eventually, expanding space carried galaxies far enough apart that gravity could no longer dominate.

About 8 billion years after the Big Bang — which is about 60% of the universe’s current age — dark energy overcame gravity, and caused the expansion to accelerate instead.

So, what is dark energy? Is it vacuum energy (the cosmological constant), quintessence, or something else entirely?

The short answer is, we don’t know.

Yet.

Dark energy remains one of the biggest questions in the history of astronomy. The final frontier of theory and discovery.

But, elusive as it is, dark energy fills in some important blanks — such as the shape of space and the future of the universe.

And that’s what we’ll explore next up.

Leave a reply to Emma Cancel reply