Imagine a time before stars and galaxies existed, before free-floating subatomic particles combined to form the first atoms, before the synthesis of the first atomic nuclei…

Wait a second — this sounds familiar!

Way back in May, we rewound the clock — so to speak — to the first millisecond of time and explored the universe’s first moments. We delved into the whacky world of quantum mechanics and antimatter. We watched as all the matter that would ever exist settled into being.

But what I didn’t tell you then was that we were missing part of the story…

This story starts in 1980, with the big bang theory.

At this point, the big bang theory was very well supported by the available evidence and was widely accepted by cosmologists. But it still had two problems: the flatness problem and the horizon problem.

Let’s start with the flatness problem.

As you may be aware from my post on the shape of space, there are three possible types of curvature that space-time might have: positive, negative, and flat.

Our universe appears very close to exactly flat. But that doesn’t make much sense…and I’ll show you why.

In order to be flat, the density of matter and energy in the universe must equal the critical density: 9 x 10-27 kg/m3.

If the density is higher than that, gravitation between all the matter is strong enough to curl space-time into a ball. It can’t be flat.

And if the density is less than the critical density, there isn’t enough gravitation going on to hold space-time flat — it’ll flay open like a saddle.

But the critical density isn’t a natural value for the universe to tend toward. It’s a sweet spot — kinda like perfectly balancing a teeter-totter.

You know how hard it would be to get the plank of this teeter-totter to balance at exactly flat, exactly parallel to the ground?

It’s kind of in the name — it’ll teeter this way, totter that way. It’s not stable. The slightest gust of wind will upset the balance.

Likewise, the critical density isn’t a density that will just “snap” into place. It’s a very specific value that the universe’s density must equal exactly — not teetering this way and that — in order for space-time to be flat.

And yet…we would seem to live in a flat universe.

It is, quite frankly, absolutely incredible that the exact amount of matter necessary to produce a flat universe came out of the Big Bang.

And then we have the horizon problem…

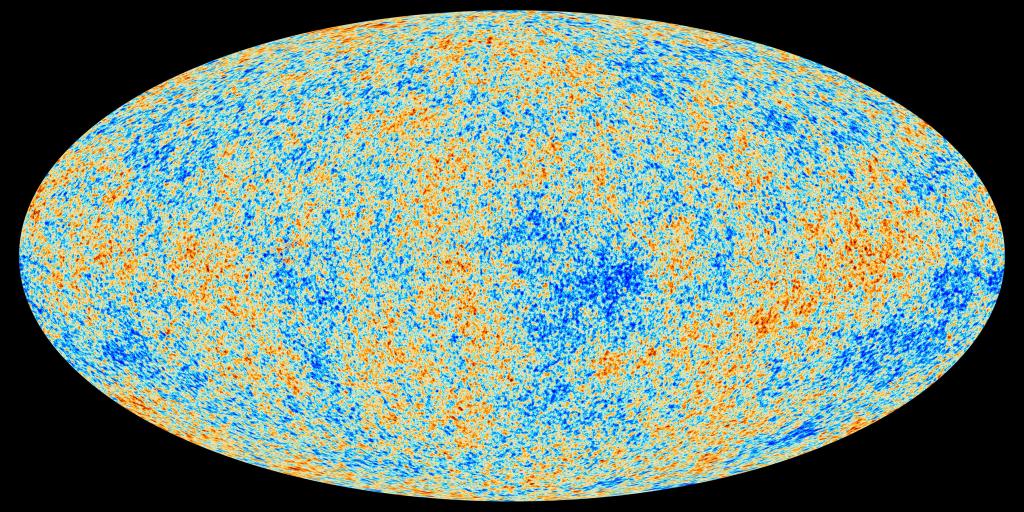

Oh hey, does this look familiar?

Yup — that’s the cosmic microwave background radiation, or CMB.

Now, remember back in June, when we covered the cosmological principle — which states that any observer in any galaxy sees the same general properties for the universe?

Part of the cosmological principle is the observation that the universe is isotropic: that is, it looks roughly the same no matter which direction you look.

And, as we noted back then, that includes the CMB.

And that is downright weird.

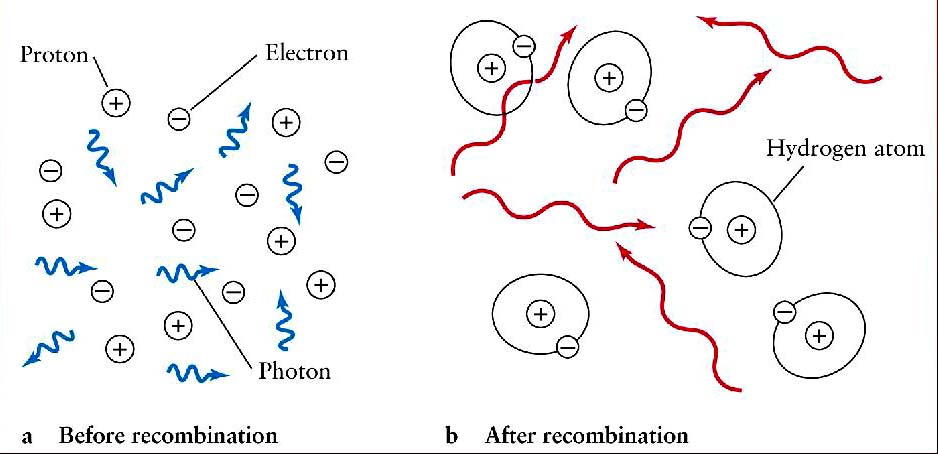

As you may remember, the CMB is the afterglow from recombination: the moment when the universe’s temperature cooled enough for protons to capture and hold free electrons, forming the first proper atoms.

At that moment, the universe became transparent for the first time — meaning that the radiation present no longer interacted with matter. The CMB is a relic from that time, a moment frozen in time.

Now, here’s the crux: recombination took place a good 400,000 years after the Big Bang.

The universe had expanded quite a bit by then. All the “stuff” in the universe was pretty spread out.

Meaning…if, today, you look at two spots in the CMB with an angular separation larger than about 1 degree, you’re looking at two bits of stuff that should never have come into contact.

Those two bits of stuff shouldn’t have been able to exchange energy and equalize their temperatures.

We should see some variation in the CMB, kinda like a spectrum — hotter swaths of the CMB gradually fading into cooler swaths, and back again.

And yet…across the entire sky, the CMB all looks pretty much the same, everywhere.

By the way, if you’re wondering what the heck this has to do with a “horizon,” think about what a horizon on Earth really is…

A horizon is the farthest you can see across a landscape. There’s land beyond it, but it’s hidden by the curvature of the Earth.

Likewise, for any one bit of “stuff” in the CMB, there is of course plenty of other bits of “stuff” in the distance. But beyond a certain distance — equal to about 1 degree of separation in our present-day sky — those two bits of stuff can’t “see” (interact) with one another. They’re beyond each other’s respective light-travel horizons.

Anyway.

The horizon problem essentially states, why the actual heck did the entire observable universe have almost exactly the same temperature at the time of recombination?

Fortunately, there is a hypothesis that solves both of these problems in one fell swoop — and it solves the problem of matter, while offering further evidence in favor of dark energy.

Meet the inflationary universe.

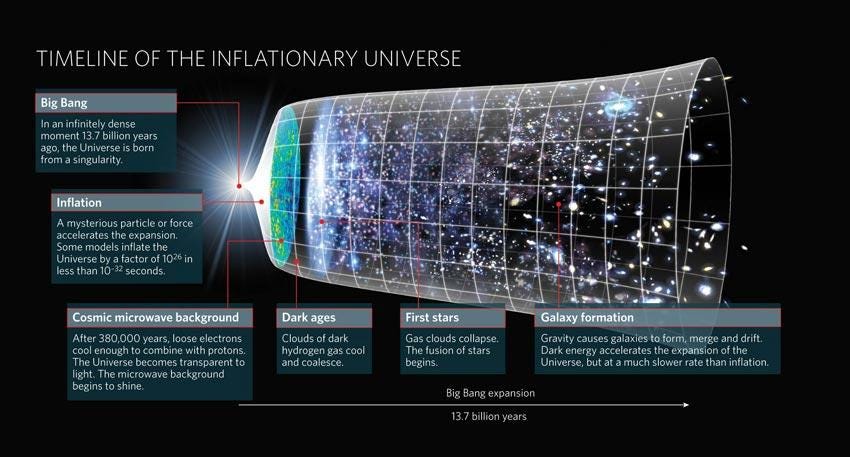

Above, you see the full timeline of the universe’s history, from the Big Bang on the left to galaxy formation on the right. But do me a favor and look more closely at the second step: inflation.

The inflationary universe hypothesis suggests that, about 10-36 seconds after the Big Bang, the universe underwent a single, sudden, and ridiculously powerful expansion.

People…that’s a ridiculously tiny fraction of a second. Specifically, 0.00000000000000000000000000000000001 seconds. (If you’re reading this on a phone screen, I’ll bet that number barely even fits across your screen.)

But it gets better. In the space of about 10-32 seconds — that is, 0.0000000000000000000000000000001 seconds (the number is four zeroes shorter) — the universe inflated in size by…drumroll…

A factor of at least 1050.

That is…a factor of at least 100,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000.

That’s crazy.

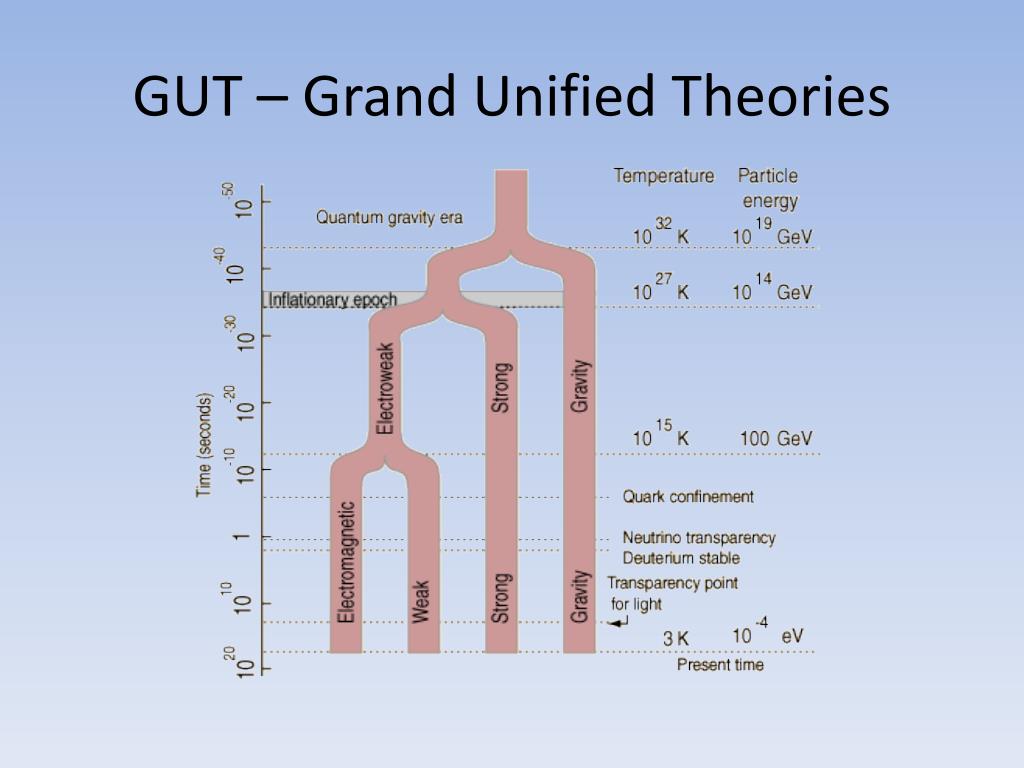

And in order to understand why, we need to turn to the four fundamental forces of nature: gravity, the electromagnetic force, the strong force, and the weak force.

In the present-day universe, these four forces act separately.

The electromagnetic force is in charge of electricity and magnetism, and it’s intimately connected with light and radiation. The weak force is in charge of radioactive decay. The strong force holds atomic nuclei together, and of course, you’re familiar with gravity already.

But in these first fractions of a second of time, the four forces were united as a team.

You see, there’s an ongoing effort among physicists to mathematically “unify” the forces — that is, to rewrite their equations as aspects of a single law. These are called grand unified theories (or GUTs).

For instance, we know from successful efforts in the 1960s that the electromagnetic force and the weak force can operate as different aspects of a single force: the electroweak force. But this only works for extremely high-energy processes. It takes even higher-energy processes to unify the other forces.

Well, people…the conditions just prior to the Big Bang are the single highest-energy conditions the universe has ever experienced.

But as soon as the Big Bang occurred, those high-energy conditions wouldn’t last for long.

At 10-36 seconds, the electroweak force and the strong force disconnected from one another.

The result?

Kaboom!

Okay, okay…it would be unbefitting of me as a science educator to leave it at that. Just as the Big Bang was not a single, localized explosion, neither was this moment of inflation.

The separation of the electroweak force and the strong force unleashed absolutely ridiculous amounts of energy — and the resulting inflation took place simultaneously across the entire infant universe.

Also note that, just as with the present-day expansion of space-time, the matter itself did not move. Individual bits of matter were carried apart by the expanding fabric of space. Inflation just made that space expand super duper fast for a ridiculously tiny fraction of a second.

This moment of inflation would have forced the curvature of space-time toward zero — essentially flattening the universe.

And it means that, prior to inflation, the observable universe was a lot tinier. Tiny enough for all the matter and energy we can see today to interact and equalize its temperature.

So, the radiation emitted at the time of recombination — observable now as the CMB — had long since had roughly the same temperature, all across the universe.

…and that brings me back to dark energy, and the solution to the problem of matter.

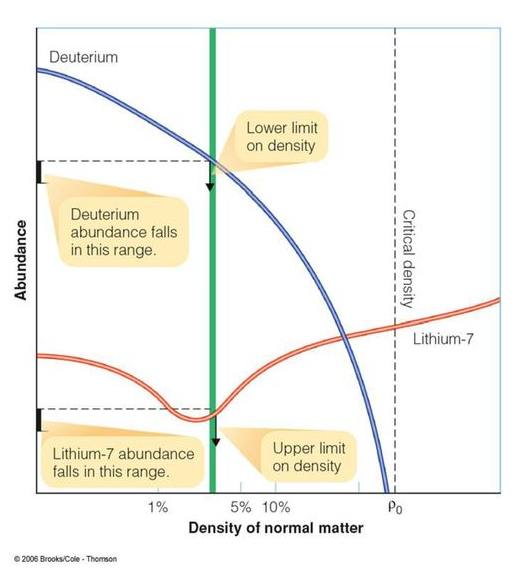

Earlier this month, we used the abundance of lithium-7 and deuterium just after the Big Bang to calculate the density of matter in the universe.

We also used gravitational lensing to estimate the amount of dark matter in the universe, and found that it outweighs ordinary (baryonic) matter by a factor of between 5 and 10.

We then added together the total density of energy and matter (both baryonic and dark) in the universe, and compared it to the critical density.

We found that the value we get doesn’t even come close. Baryonic matter comes out to about 4%-5% of the critical density. Add in dark matter, and we still get only about 30% of the critical density.

But observations indicate the universe is almost perfectly flat, and inflation predicts that it must be so.

How can this be?

This is where dark energy comes in.

Einstein’s famous equation, E=mc2, holds that energy and matter are interchangeable (and I explain why here). And dark energy is some type of energy, causing the expansion of space-time to accelerate — we just don’t know what causes it.

Just like any ordinary form of energy, dark energy is equivalent to some amount of matter spread throughout space. We can add its density to that of baryonic matter and dark matter, equaling the actual total density of the universe.

Now the total density of the universe can equal the critical density — and space-time can be flat. That is quite possibly the most important blank that dark energy fills in.

But that still leaves us with a critical question…

Is any of this accurate? Can we confirm this hypothesis — that of the inflationary universe?

That’s what we’ll cover next up.

Leave a reply to disperser Cancel reply