Stars are hot. Space is cold. We’re all familiar with that, right?

Ok, good.

Technically, it’s more complicated than that. Space isn’t completely frigid—absolute zero, the temperature at which there is no heat whatsoever, is purely theoretical and not thought to exist in the universe. But it is pretty darn cold.

And stars aren’t always very hot—there is one newly discovered star that’s only as hot as fresh coffee. (It’s a brown dwarf, and if you go by the definition of a star as an object that’s ignited hydrogen fusion in its core, then it doesn’t actually count.)

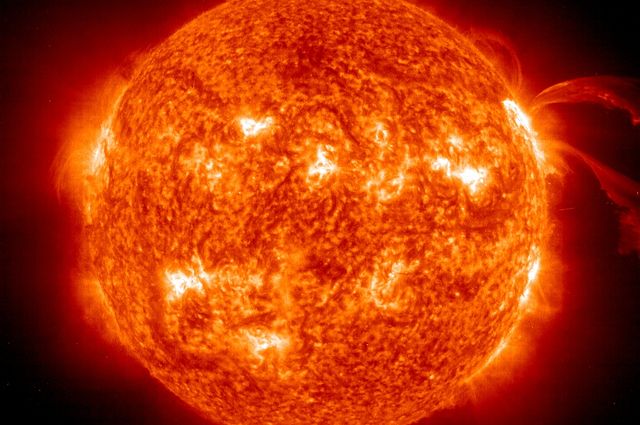

In general, though, stars are pretty darn hot. Some special types of stars reach up to 200,000 K—that’s 359,540.33℉. Our own sun is about 5,778 K, which much cooler, but still almost ten thousand degrees Fahrenheit.

As a rule, we can think of stars as being much hotter than the space in between…except in the case of coronal gas.

Continue reading