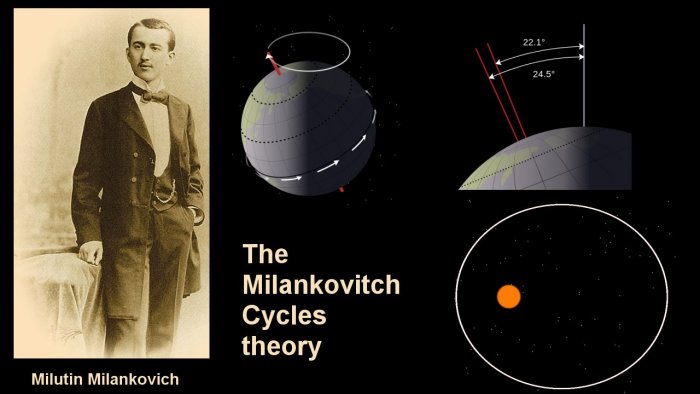

The Yugoslavian meteorologist Milutin Milankovitch is known for coming up with the idea of orbital forcing, also known as Milankovitch cycles. Orbital forcing is a fancy term for certain changes in Earth’s orbit, which are precession, obliquity, and eccentricity.

I’ve written about all three of these before, but here’s a brief overview:

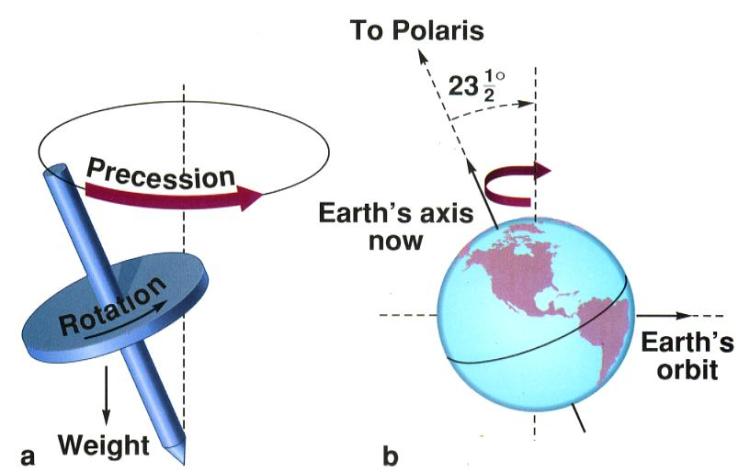

Precession is the motion of Earth’s axis like a spinning top. Imagine the Earth’s day-by-day rotating motion as that of a top. What do tops also do? They wobble.

Although I’ve written about obliquity, I haven’t used the term before. It’s a fancy word for how the tilt of the Earth’s axis doesn’t stay at the same angle. It changes a bit over a very long period of time, ranging between 22° and 24°.

Eccentricity refers to the changing shape of Earth’s orbit. You might know that it’s not a perfect circle—it’s an ellipse, which I’ll talk about in more depth later. What you might not know is that how elliptical it is—that is, how far it is from being a perfect circle—also changes a bit over time.

These motions are all very well established in science today. We know that they each have an effect on Earth’s climate, and together they cause the ice ages. But Milutin Milankovitch, the scientist who first came up with the idea, had a lot going against him.

Even though Milankovitch’s theory was right, he lived in a time before there was any way to test it. It’s one of those instances where scientists give credit where credit is due…but it’s almost too late.

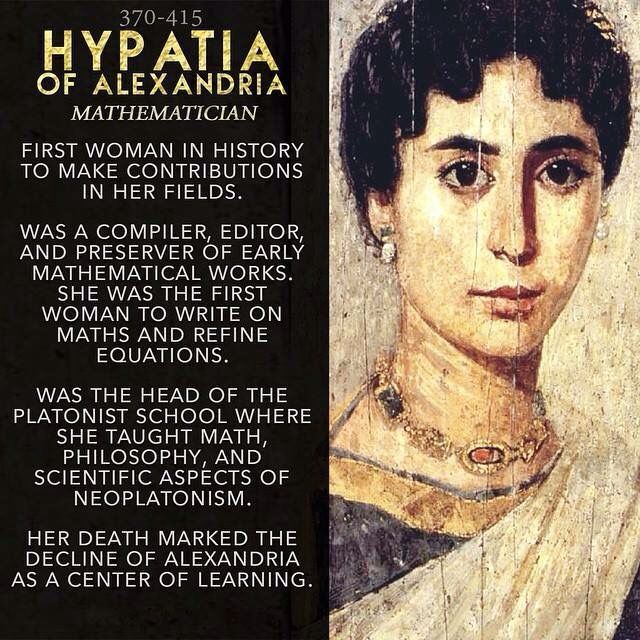

Milankovitch was fortunate that his theory did end up getting named after him. Other scientists have been less fortunate. It’s not well known that, while the classic astronomer Johannes Kepler suggested that orbits were elliptical in the first place, he wasn’t the first to come up with the idea—that distinction belongs to a woman named Hypatia.

It’s not surprising to me that Hypatia, as a female scientist, never did get the widespread credit she deserved. But Milankovitch did, and for that we can be grateful.

Milankovitch’s credit, however, came about fifty years after he came up with the idea. He suggested that Earth’s orbit, precession, and tilt affected the climate in 1920, but it wasn’t until the mid-1970s that scientists actually began to seriously consider his hypothesis.

These scientists weren’t around millions of years ago to observe the effect of orbital forcing on Earth’s climate. But the oceans were, and in the 1970s, scientists finally had the technology to measure the age and temperature of ocean sediments.

What this basically means is that they scuba-dived to the seafloor, then drilled down to collect what we call “cores.”

Cores are samples from the seafloor, but they’re much more than that. They give us a glimpse of the different layers of the seafloor, which have been layered over one another over the course of millions of years.

And because they’re so old, they’re a glimpse into the past. By measuring how old they are—easily done—and what temperature they were when they were brand new—also easily done—scientists can find out the temperature of the ocean at certain times in Earth’s history.

Why are ocean temperatures so important, then?

Well…I don’t even understand the physics here myself, but I gather that ocean temperatures pretty much correspond to global temperatures. As in, if you can find out the temperature of the ocean, you can find out the average temperature of the Earth.

Scientists tested Milankovitch’s theory by studying these cores from the seafloor, and what they found was encouraging. They already had models of how orbital forcing was likely to have looked in the past, and the seafloor samples lined right up.

It looked like the Milankovitch hypthesis was about to be proven accurate.

But then contradictory evidence turned up…

See, in science, you can’t just accept one piece of the evidence as proof that what you think is right. You have to look at the whole picture, and if any evidence goes against what you think—no matter how much you love what you think—you have to seriously reconsider your hypothesis.

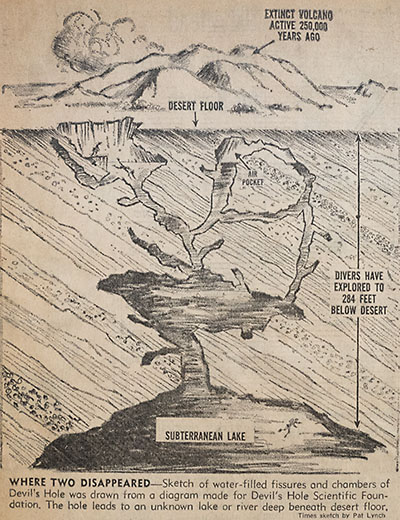

Just one bit of contradictory evidence is enough to derail a scientific hypothesis. And for Milankovitch, this evidence came in the form of Devil’s Hole in Nevada.

Its depth would be scary if it were’t filled with water…

But Devil’s Hole’s depth also means that it’s a truly ancient repository for rainwater.

Why does that matter? Because said rainwater has left deposits of the mineral calcite on the walls of the crack.

And in laboratories, scientists could measure the age of the calcite and the temperature of the rainwater at the time.

This way, they could now see thousands of years of Devil’s Hole’s history of temperatures. And what they found was a surprise…

It seemed, unfortunately for Milankovitch, that average temperatures around the globe had been warming up thousands of years too early to line up with orbital forcing.

The findings at Devil’s Hole could be taken as a reason to disregard Milankovitch’s hypothesis entirely. But one thing that’s important to realize about the nature of a scientist is that curiosity transcends almost any defeat.

At this point, scientists had equal evidence for and against Milankovitch’s hypothesis. Suddenly, it wasn’t just Milankovitch who was excited about the results—scientists hate contradictory evidence, and this triggered a scramble to understand what was going on here.

Both samples of data couldn’t be right, could they? Had scientists just measured the data wrong? Or was there something in the bigger picture they weren’t understanding yet?

None of this was even close to enough evidence to adopt or dismiss the Milankovitch hypothesis. Crazier ideas suggested over time have been true. People once believed that the Earth was flat, and the idea that it was a sphere was insane. So was the idea of the sun being the center of the solar system, and so was Einstein’s famous theory of relativity.

So scientists went on studying the data. And in 1997, almost thirty years later, they got their answer. It turned out, unsurprisingly, that the samples at Devil’s Hole only opened windows into Nevada’s local past. They didn’t correspond directly to global temperatures.

What did this mean? Both samples were accurate. But the cores from the seafloor actually referred to the average global climate, just as did Milankovitch’s hypothesis. And because they lined up with the models of orbital forcing, Milankovitch was proven right.

For now, that is. If evidence was found that called what’s now accepted as the Milankovitch theory into question, it would have to be tested again. And scientists would have to ask themselves, just how well do we understand climate?

For now, the Milankovitch hypothesis—that Earth’s orbit, precession, and tilt affect global climate over millions of years—is accepted as scientific fact.

You should look up the contribution of James Croll (sp?). He also put forward an orbit related hypothesis, and did so before Milankovitch, but Milankovitch described the mechanism of orbital forcing in a mathematical rigorous way.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gotcha—definitely will do, when I find the time 😊

LikeLike