Here’s a visual binary that just about stretches the limits of the definition. It’s a star, though you’ll never see it like this with the naked eye. Specifically, this is Sirius, the brightest star in the sky.

But if you look closely on the top left, you’ll see a tiny dot just peeking out from behind Sirius’s brilliance. That’s Sirius B, this bright star’s faint companion. Together, they’re known as Sirius A and Sirius B.

It’s tradition for astronomers to name all the stars in a system the same thing, but it also makes sense. Most of them aren’t obvious. You might look at some ordinary-looking star in the sky, say…Antares. But as it turns out, Antares has a barely-visible companion.

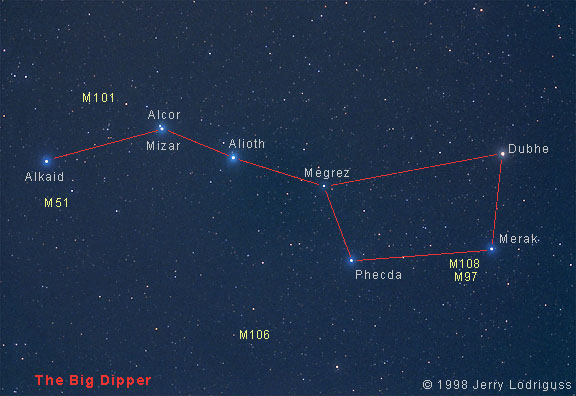

The visibility of visual binaries has a wide range. Consider the famous double star in the Big Dipper, Mizar.

Alcor, Mizar’s companion, is actually just barely visible to the naked eye. But try to make out the other stars in this system—which is, in fact, suspected to be a quadruple star system—and you’re out of luck. You need a telescope…or even a spectrograph.

But we’ll get into that in my next post. For now, let’s just look at the visual binaries, no expensive astro-tech required.

Mizar and Alcor are a fairly obvious sight. But just because two stars are clearly a double—appearing practically on top of one another in the night sky—doesn’t mean they’re actually a binary.

Take Albireo, for instance.

Whether or not this striking pair of stars is actually a true visual binary is debatable.

Albireo can be found high overhead in the northern hemisphere’s constellation Cygnus, the swan that gracefully rides the trail of the Milky Way across the sky. It’s specifically in Cygnus’s head.

While Albireo is a bright star even to the naked eye—those that make up the constellations generally are—you need a telescope to see its blue companion. And what a sight that is.

Astronomers have long studied Albireo. It presents an astronomical quandary. These two stars have been observed together for thousands of years, which suggests they are actually near one another in space, not just an optical illusion.

As much as this man looks like he’s holding up the Leaning Tower of Pisa, I doubt he’s physically anywhere near it. And the stars behave the same way in the night sky.

But no…the two stars of Albireo have been observed near one another for an astronomical length of time, which suggests they’re traveling together, rather than drifting apart, as the stars of the Big Dipper are wont to do.

Stars that aren’t traveling together are likely to distort the shape of a constellation over time. But do you notice Mizar in this animation? Alcor isn’t shown here, because if it were, it would faithfully follow Mizar, not get lost in the emptiness of space.

Albireo’s stars seem to be traveling together. But does this make them an actual binary, or just an optical double that’s lucky enough to stay friends?

Some astronomers would tell you that it’s entirely possible Albireo A and B are gravitationally bound. But we haven’t discovered conclusive evidence that they travel in orbits around one another, not just together through space.

If they do…well, what with the movement we’ve seen from them so far, their orbital periods would have to be between tens and hundreds of thousand of our Earth years.

It’s still entirely possible. The fact that we haven’t had a whole lot of thousands of years to observe Albireo—thanks in part to our present-day longevity as a species—doesn’t mean that in thousands of years, we’ll see movement indicative of actual orbits.

What would the orbits of binary stars look like, anyway?

Since we’re talking about visual binaries, specifically, we have the bonus of being able to see them orbit one another through a telescope.

Meet Castor, one of the brighter stars in the constellation Gemini. Perhaps unsurprisingly, as around 80% of stars are visual binaries, Castor has a companion.

Let’s take a close look at what this diagram is actually showing us. There are seven individual images of the stars here, photoshopped together onto an illustrated background that diagrams roughly how their orbits work.

Essentially, the orbit in the middle is just a drawing. But it’s a drawing of what’s going on with the less massive star’s orbit in each real picture that’s been taken of these two stars together.

Notice how, in each picture, the stars have changed position a little? In April 2000, Castor A—the larger and brighter one—is above Castor B. But twelve months later, Castor B has swung around A in its orbit and is now to the left.

Ten months later, Castor B has moved a bit more. By December 2003, it’s more than opposite its position in April 2000. And a month later, half its orbit is completed.

Keep in mind that Castor B isn’t the only star that’s moving here. Castor A will move a little too, as its less massive companion’s gravity tugs it around a bit.

If two equally massive stars orbited one another, their orbits would be the same size, and in fact would even follow close to the same path. The key is that they both orbit their center of mass, the balance point of their orbital system.

Visual binaries are binary stars that can be seen separately through a telescope, or in some rare cases, with the naked eye. But that doesn’t mean it’s going to be easy.

Here’s Sirius again…in a normal telescopic view.

When you look at the starry night sky through a telescope, it’s hard to figure out what stars you’re looking at.

We usually recognize more familiar stars by their brightness among the fainter stars spread across the sky, but even those faint stars often seem bright through a telescope.

Sirius, however, is the brightest star in the night sky. It’s not unusual for it to appear pretty obvious against its starry background.

Still…I don’t see the fainter Sirius B anywhere in this image, do you?

Well, now I see it.

This is the Hubble Space Telescope’s view of Sirius B. Because this image was taken through a telescope, Sirius is a visual binary. But Hubble’s equipment is way more high-tech than anything amateur astronomers can get their hands on.

Don’t get me wrong. Sirius is plenty possible to “split,” as astronomers would say, even with amateur-level scopes. A few members of my astronomy club, the Temecula Valley Astronomers, made a challenge of it once. I think at least one of them was successful.

Some visual binaries are difficult to split…some are easier. There are double stars that aren’t binaries at all. And there are double stars that are nowhere near each other in space, period.

No matter what they are, though, they’re cool to look at and study. Next up, I’m going to take a closer look at a different type of binary system: a spectroscopic binary.

Very nice explanation

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good to hear 😊

LikeLike

Nice👍👍👍

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike

I think you should present this at the next TVA meeting.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Fantastic post.

LikeLiked by 2 people