Ever seen this before?

It’s not a sight that most of the developed world gets to see–at least not all the time. Light pollution from major cities completely obscures this view. Even in the suburbs where I live, I can kind of make it out–because I know where to look and what to expect.

The best way to really see it is to head out into the desert. Or the open ocean. Really, any place that’s a bit geographically removed from civilization. Growing up, Joshua Tree National Park was always my go-to for dark skies.

Even on an exceptionally dark night, though, you won’t necessarily see this. You’ll definitely be wowed by the vast, bright sprinkling of stars overhead, more than you ever see under less than ideal conditions. But the image above was taken with a long exposure.

That is, the camera shutter remained open for a while to collect more light for one image than your eyes ever will. You and I pretty much only see one image per moment.

So what is this gorgeous, hazy band, anyway?

You probably guessed it from the title: this is our own galaxy, viewed from the inside.

Humanity has observed this band of stars, gas, and dust–dubbed, by the ancient Romans, the Milky Way–for practically as long as we’ve walked this earth. I’m not sure what the earliest humans were thinking when they looked up at the night sky, but it would have been even more clear to them back then, without civilization to dilute the light in the sky.

So, of course, the “milky way” is hardly a new discovery. When we talk about “discovering” our galaxy, we really mean discovering what the heck the Milky Way actually was.

And that wasn’t easy.

The story starts when, in 1610, Galileo Galilei observed the Milky Way through his telescope and realized that it was made up of an absolute crap ton of stars.

Okay, so maybe he didn’t use that language when he spoke of his observations…

Galileo’s contribution to the discovery of our galaxy continues a broader story we started way back with our discussion of classical astronomy. We started with Aristotle’s view of the “universe” (which was almost entirely wrong).

We continued through the contributions of Ptolemy, Copernicus, and Tycho Brahe, who all had revolutionary ideas important to astronomy’s development as a field of study. But they were all shackled by a single problematic idea–that of uniform circular motion–which kept their models of the universe painfully inaccurate.

And lastly, we discussed Kepler and Galileo, who together advanced astronomy into the modern age with the first truly scientific and mathematical observations, measurements, and experiments.

What’s important to realize is that in Galileo’s day, concepts of the “universe” still involved nothing more than the sun, orbiting planets (and a few moons), and a sphere of stars that remained fixed in place. Today, we know of most aspects of that model as our solar system, and the universe is something much broader. But back then, that was all they knew.

So when Galileo identified the familiar Milky Way as a thick band of stars that wrapped around the Earth, modern astronomy was in for its next major expansion–the concept of a “star system” beyond the solar system.

Anyway, later astronomers realized what the shape of this great “milky way” of stars meant. It wrapped around the entire sky, and it was easy to imagine that humanity–that is, Earth–was sitting in the middle of a disk of stars.

To look directly at the thick band of stars was to look straight through the plane of the disk to the edge, where the stars were thickest. But when one looked at the broad expanse of emptier sky around the band, they were looking “up” and “down” through the flat faces of the disk.

It must have looked a little like this…

Pictured above is something that most of you probably have never seen before. This is, in fact, a grindstone, technology from about 300 years ago.

In 1750, more than a century after Galileo’s observations of the Milky Way, Thomas Wright described the star system as a “grindstone universe.” And of course, we can understand why he would use the term universe. Like the sun and planets before it, the “star system”–which would come to be understood as a galaxy–was all we knew of the universe.

Along come the next characters in our galaxy’s story: Sir William Herschel and his sister Caroline.

You might recognize these people from my very recent (for once!) post on deep-sky catalogs. The Herschels compiled observations of many of the objects that would later be added to the New General Catalog (NGC).

Their role in our galaxy’s story is similar to the roles of Ptolemy, Copernicus, and Tycho Brahe in understanding our solar system. They tried to map out our galaxy’s size and shape, and they made important observations and advancements, but there were critical weaknesses in their methods that led to major inaccuracies.

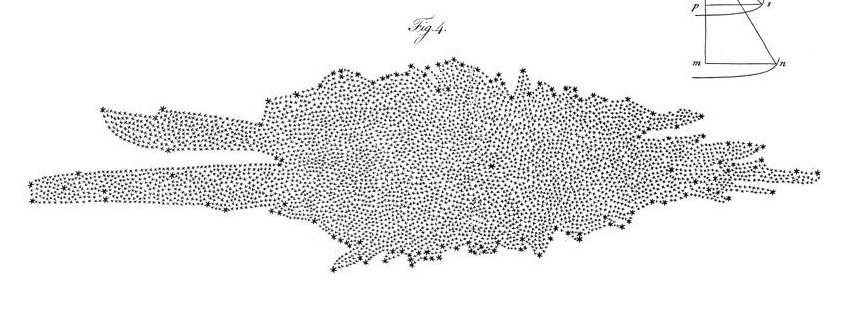

Here’s their concept of what the galaxy looked like…

It’s…not really correct. Not by a few miles.

(Okay…way more than that. We’re talking about astronomical distances here.)

The Herschels called their method “star gauging.” They counted the number of stars visible in different directions. They hypothesized that if they could see many stars in one direction, the edge of the star system was farther away, and if they could see fewer stars in another direction, the edge in that direction was closer.

On the surface, it was a fairly reasonable approach. But just as the concept of uniform circular motion shackled classical astronomy, the Herschels were shackled by their own incorrect assumption: that they could see to the edge of the star system.

Their model placed the sun near the center of the star system. But, in fact, the giant, weird-looking prong shapes on the left side do not represent the real structure of the galaxy. This is the place where great interstellar dust clouds obscure our view of the stars beyond.

The sun is actually nowhere near the center. More than half the galaxy is hidden behind those great dust clouds.

And that’s not the only place where the Herschels’ assumptions fell through. All over the place, smaller dust clouds block our view of the stars beyond–and that’s where you get all the smaller gaps along the edges of their diagram.

What’s more, I can’t even tell if the Herschels’ representation is supposed to represent a profile view of the galaxy or a view looking down at the flat side of the disk. Either way…it’s missing a lot of stars.

Clearly, the Herschels got a lot of things wrong. But honestly? So does everyone–especially the first people to try to figure out the previously unknown! Remember, there’s no such thing as “failure” in science. Getting a wrong answer just means you’ve eliminated one possibility, and you’re that much closer to getting it right.

Notice that, despite the parallel stories of discovering our solar system and our galaxy, we’re talking about things in much more scientific terms now. The Herschels did their work less than 200 years after Galileo’s time, but in that time, astronomy as a field had advanced by leaps and bounds.

Galileo observed that the Milky Way was made of stars. Other astronomers, like Thomas Wright, soon figured out the rough shape of that expanded “universe.” William and Caroline Herschel developed an early method of mapping the star system. Each and every one of them contributed important advancements to our understanding of the universe.

My thought!!.

It seems that the science concerns Astronomy is based on “Hypothesises”.

To get shapes and diagrams of galaxies, a probe has to travel many light years deep into space/universe. This could enable high resolution cameras from that space probe to capture photographs of the REAL Object(s).……!!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think you might enjoy my post on “Exploring the Milky Way’s Spiral Arms” (found here: https://scienceatyourdoorstep.com/2023/01/25/exploring-the-milky-ways-spiral-arms/) In this post, I explain the evidence astronomers have that the Milky Way Galaxy is a spiral shape.

LikeLike

I think it’s amazing that we’ve worked out what the milky way even is…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know, right?

LikeLiked by 1 person