I know…that seems like a strange question to ask, doesn’t it? Out of context, it makes no sense at all. What are we even talking about? The curvature of what?

Cosmology is full of questions like this — questions that have almost no grounding in our daily human lives. But the thing about cosmology is that, if we find answers to these kinds of questions, we can discover the literal fate of the universe.

In the case of curvature, we’re talking about the shape of space (as we explored in my last post).

And that shape of space — literal space, the vacuum itself — might determine whether our universe expands forever, or crunches back together in a reverse-Big Bang.

If I don’t manage to blow your mind this time, I’ll be personally offended 😉

Okay, I know what you’re probably thinking.

How can the shape of space determine the fate of the universe?

Don’t worry, we’ll get to that. But first, we need to figure out what the heck the shape of space even is.

As we explored in my last post, there are three different possibilities:

The universe could have positive curvature (like a sphere), negative curvature (like a saddle), or zero curvature (just a flat plane).

A positively-curved universe would be a closed model. As you might be aware, the universe is currently expanding; if it’s closed, then it’ll eventually rebound back on itself and contract into the high-density state of the Big Bang.

This idea has been called the “big crunch.” But there’s another fun feature that comes with a closed universe…

Remember how we discovered the universe’s expansion in the first place?

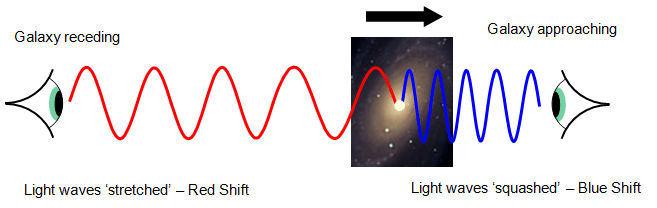

One surefire way to estimate the distance to any galaxy is to measure its redshift. But we’re not talking about a Doppler redshift — we’re talking about cosmological redshift.

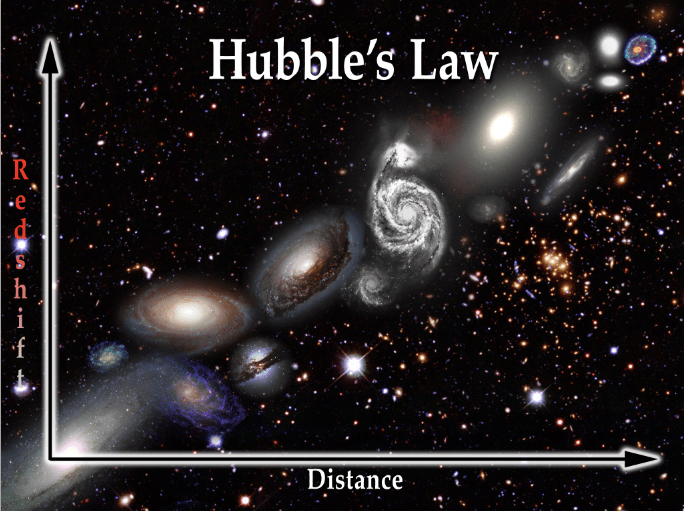

Cosmological redshift is directly proportional to distance, which gives rise to the Hubble Law.

Cosmologists quickly realized what these redshifts meant: galaxies are receding from one another. But they’re not moving through space. They’re being carried apart by expanding space.

Imagine a closed universe, sometime in the distant future. Space would eventually rebound and contract, like releasing a stretched rubber band. Now galaxies would be carried closer together — by shrinking space.

Would we then observe a cosmological blueshift?

If the universe is negatively curved or flat, though, cosmological blueshift would remain forever impossible. In these open models, the universe expands forever.

But which is it?

More importantly…how the heck do you even figure that out?

It all comes down to the universe’s density.

Okay…what? What does that even mean? How can density determine the shape of the universe — or its future?

It’s simpler than it sounds. It depends on something you are intimately familiar with: gravity.

Gravity is what anchors you to the surface of the earth. It’s why objects thrown in the air fall back down. It’s why we need technology to keep planes and helicopters aloft — they don’t just float. It’s why it’s so hard to get into space.

It’s what keeps the Earth in orbit around the sun…and it’s what holds galaxies together.

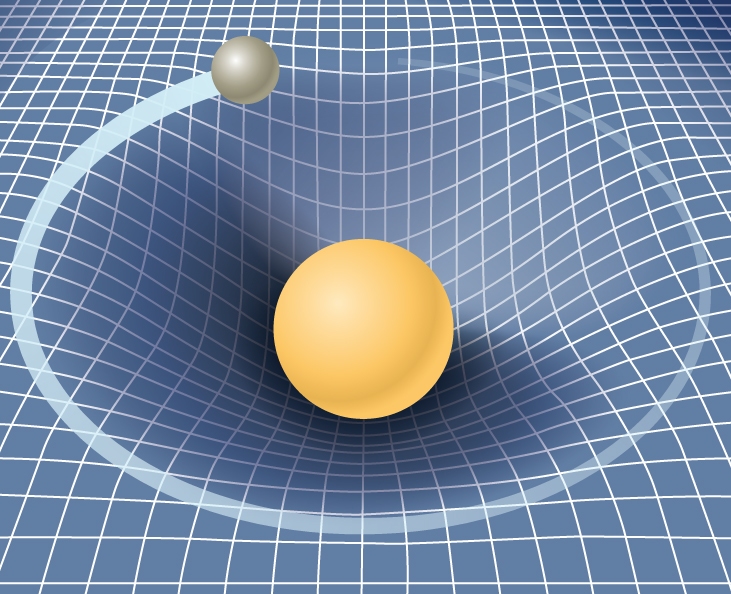

And, according to Einstein’s theory of general relativity, gravity is curvature of space-time.

Hmmm…wait a minute. Haven’t we just been talking about the curvature of space?

Yup. There’s the connection.

Gravity curves space, and that’s how orbits work. Massive objects like the sun deform the fabric of space, and less massive objects like planets are drawn toward those dimples in space-time.

Gravity depends on mass. More massive objects have more gravity — that is, they create more pronounced curvature in space-time.

And remember that, also according to Einstein — this time according to E=mc2 — matter and energy are interchangeable. So, energy “matters” too. (Ha, ha — see what I did there?)

The question is, does the universe have enough mass and energy for gravitation to contract all of space into a closed ball? Or is the universe’s density low enough that it can be open — that is, either flat or negatively curved?

Now we need to figure out what “low enough” actually means.

In order to answer that, we can think of the universe as kind of like a rocket…

When the fuel ignites, that’s the Big Bang. The rocket lifts off — that’s the current state of expansion. What comes next depends on two things: the gravity of the planet it’s leaving, and the velocity of the rocket.

Let’s say the rocket is launched on a high-mass planet. A certain velocity is needed to escape the planet’s gravitation — escape velocity. If the rocket doesn’t reach that speed, gravitation will win. The rocket will fall back down to the ground.

This is a closed universe. The expansion from the Big Bang isn’t enough to counteract gravitation. The universe rebounds and collapses.

But let’s say the same rocket is launched at the same velocity from a smaller, lower-mass planet. This time, its velocity exceeds escape velocity. The rocket will drift off into space, indefinitely.

Now we’re talking about an open universe — either flat or negatively curved.

Note that depending on the universe’s future — expansion or collapse — our estimate of its age changes.

Expansion in a closed universe is unsustainable and can’t have begun long ago, cosmologically speaking; such a universe would be younger, and the Big Bang would have been more recent.

An open universe, on the other hand, will maintain its expansion indefinitely, and the Big Bang would have occurred further in the past.

Even a flat universe must have had a more recent Big Bang than a negatively curved universe. Its expansion would have just barely overcome gravitation, and would slow down “soon” (again, cosmologically speaking).

Now we need to figure out how fast our rocket is traveling — that is, how fast our universe is actually expanding. And we can do this using our old friend, the Hubble Law.

According to the Hubble Law, a galaxy’s cosmological redshift is proportional to its distance.

Cosmological redshift indicates the speed at which the galaxy appears to be moving away from us — more specifically, the rate at which expanding space is carrying the galaxy away from us.

That is, the rate at which the expansion of the universe is carrying the galaxy away from us.

This is how we get the rate at which the universe is expanding.

Now, I don’t know about you, but it seems like a royal pain in the behind to find the apparent recessional velocity (speed of recession) of every single galaxy in the whole dang sky. Thank goodness we have a convenient shortcut: the Hubble constant.

The Hubble constant, H0, summarizes the apparent velocities of all galaxies. It comes out to roughly 70 km/s/Mpc (kilometers per second per megaparsec).

This doesn’t answer our question of what curvature the universe has, but it does narrow down our options. Now, we can find which density would mean which type of curvature.

(Don’t worry about the Ω in this graphic — that’s just the Greek letter “omega,” which represents density in general relativity.)

The critical density — 9 x 10-27 kg/m3 — is the density the universe must have if space-time is flat.

That’s just about 6 protons per cubic meter. Which is…really not very dense at all.

If this is the actual density of our universe, then there isn’t enough mass for gravitation to stop the expansion. There is no “big crunch.” The universe expands indefinitely, like a rocket drifting listlessly into space, and space-time is flat.

If the density is higher than the critical density, then our universe must be positively curved and closed. The “big crunch” is inevitable, and the Big Bang was a (relatively) recent event.

On the other hand, if the density is lower than the critical density, then our universe must be negatively curved. The Big Bang would have occurred much further in the past.

So which is it, then?

As you might imagine, it’s not easy to calculate the actual density of the universe. But we do have a clue in the form of globular clusters.

Globular clusters are mysterious objects (and eventually, we’ll explore them on this blog1). One thing we do know is that, based on analyses of their stars, they are some of the oldest objects in the universe.

In particular, Messier 92 here is about 13.8 billion years old.

As one astronomer once put it, “You can’t be older than your mother.” There can’t be star clusters in the universe that are older than the universe itself.

If the universe is at the very least 13.8 billion years old, that would place the Big Bang long enough ago for the universe to have negative curvature. This would mean a saddle-shaped, “open” universe.

Spoilers: it’s not.

That’s because we’re missing a piece of the puzzle. But we’ll get to that later! Next up, we’ll take a stab at figuring out the density of the universe.

- Updated to reflect that research has advanced since this post was first published; now there is an emerging theory on globular clusters, which I have a planned post on coming soon. ↩︎

Leave a reply to Simon Cancel reply