Cosmologists used to think that gravity alone determined the shape of the universe, and that shape, in turn, determined its future. But that raised a lot of problems.

Gravity works by curving space-time, so it can also force the fabric of space to contract. It would then slow the universe’s expansion from an originally faster rate.

The universe would have reached its current scale in less time than the current rate of expansion implies — less than 14 billion years, perhaps significantly so.

But some globular star clusters are around 13 billion years old — and stars didn’t begin forming immediately after the Big Bang. The universe must be older than that.

Dark energy solves this problem, and more…

First, let’s backtrack a bit — to the Hubble time.

Near the beginning of our cosmology unit, we estimated how long ago the Big Bang occurred — that is, how old the universe is.

We can do this by measuring the present-day separation between galaxies.

We know the galaxies’ positions now; we know that they started scrunched together. We can find their speed from their cosmological redshifts based on the Hubble Law. From there, it’s a simple matter of finding the time they took to move from Point A to Point B.

Now, I don’t know about you, but it seems like a royal pain in the behind to do this calculation for every galaxy in the whole dang sky. Instead, we can use the Hubble constant, H0, which summarizes the separation between all galaxies.

The Hubble constant has units of km/s/Mpc, which is a speed divided by a distance.

Flip the Hubble constant over (take the reciprocal), and you now have a distance divided by a speed — which is the equation for time.

We then convert the megaparsecs to kilometers so that all the distance units are the same and cancel out, leaving us with a time in seconds. And for convenience’s sake, we convert seconds to years — because the number of seconds since the universe’s beginning is going to be an absurdly massive number.

That gives us the Hubble time:

Now we can plug in any value for H0. That will give us the estimated time since the Big Bang for any given rate of galaxy recession.

The current best estimate for the Hubble constant is just under 70 km/s, which puts the Big Bang at roughly 14 billion years ago.

But that is not necessarily accurate.

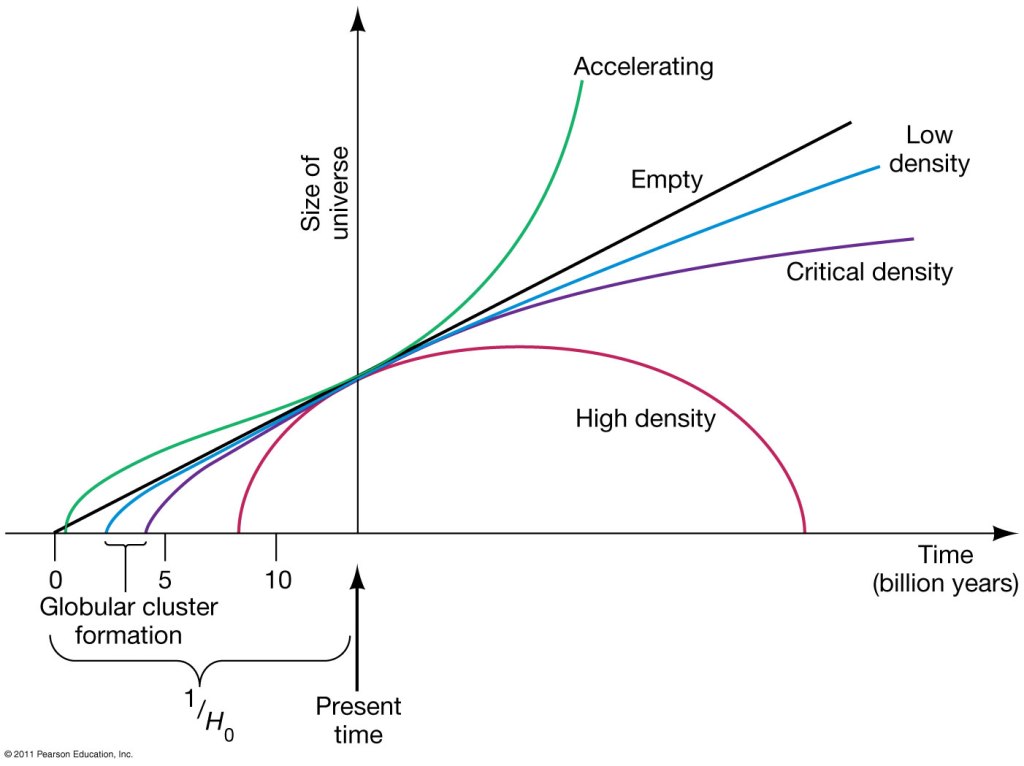

The above graphic represents the Hubble time as 1/H0 (remember, it’s literally just a reciprocal of H0).

The Hubble time is the time since galaxies were all compressed together in one spot…if their recessional velocity has remained constant.

That would, it would seem, require a universe without gravity. Because even as expanding space carries galaxies apart from one another, gravity would counteract that, pulling them back together.

The expansion would slow.

A universe whose age is actually equal to the Hubble time would need to be totally empty — no energy, and no matter, dark or otherwise. Certainly no life, no people. It would be “empty,” as the graphic above puts it.

…or would it?

If there is a force that can counteract gravity, then the universe’s past and future is no longer dependent on gravity.

Also, think about what acceleration literally means. The universe is expanding faster now than it was in the past.

Flip that statement around: the universe was expanding slower in the past than it is now.

In the past, the expansion rate was slower. The current separation between galaxies would have taken longer to reach.

The universe can be older.

Remember what we were saying before, about some globular star clusters being around 13 billion years old?

In particular, Messier 92 here is about 13.8 billion years old. It’s one of the oldest globular clusters known.

As one astronomer once said, “You can’t be older than your mother.” The universe must be older than its oldest “occupants.” So it’s got to be older than 13.8 billion years.

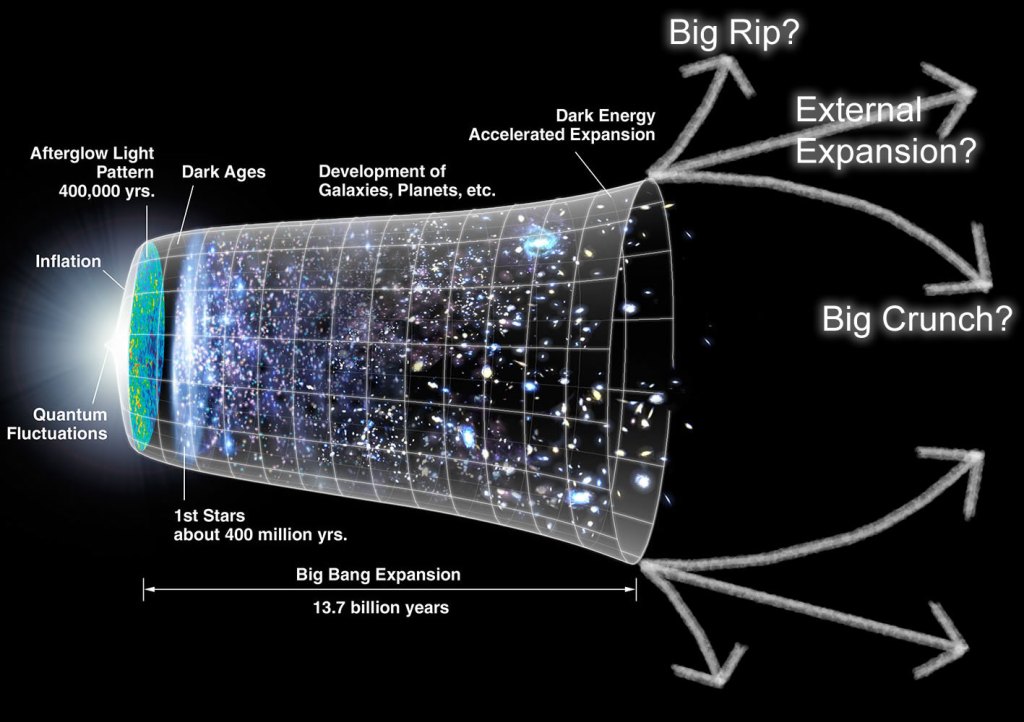

And globular clusters are hardly the oldest known objects in the universe. The earliest newborn galaxies can be observed even farther back, and the first quasars — erupting supermassive black holes — are even older, as you can see below.

Acceleration allows for this.

If the expansion of the universe is currently accelerating, then it would have been expanding more slowly in the past — and it would have taken longer to reach its current scale.

Long enough to place the Big Bang before the formation of the earliest quasars, galaxies, and globular clusters.

Now, notice that in the graphic above, the lines for the “empty” and “accelerating” universes begin in close to the same place. This is purely coincidental. The Hubble time, calculated for a universe with no matter or energy, just happens to roughly equal the actual age of our accelerating universe: about 14 billion years.

And just as acceleration accounts for the universe’s past, so too does it determine its future.

For decades, cosmologists said that “geometry is destiny.” That is, the shape of space determines its fate. There are three possible types of curvature that space could have: positive, negative, and flat.

In a reality where only gravity dominates, the flat and negatively curved models must expand forever; there is not enough matter present for gravitation to stop the expansion. On the other hand, a positively curved universe must eventually rebound and contract under the influence of gravity.

But gravity does not dominate.

Dark energy — whatever the heck it is — acts as an antigravity force. And that means that even a positively curved universe may expand forever.

Our universe’s future depends not on its geometry, but on the nature of dark energy.

And that is the biggest question left in cosmology.

What the heck is dark energy? Is it vacuum energy? Quintessence? Something else entirely? How does it work? Is it constant? Is it changing? How has it worked in the past…and how will it work in the future? Will there be a “big rip”? A “big crunch”? A “big freeze”?

We don’t know.

But there’s a lot that we do know — enough that we’ve since modified the original big bang theory. And that’s what we’ll explore next up.

Leave a reply to Emma Cancel reply