In 1915, Einstein published his theory of general relativity. This theory predicts that, since gravity works by bending space-time, it also determines the shape of space — and the shape of the universe as a whole.

In 1929, Edwin Hubble observed that most galaxies appear to be receding from Earth, and their redshift is proportional to their distance. This became known as the Hubble Law, and indicates that the universe is expanding.

In 1990, the launch of the Hubble Space Telescope — named for Edwin Hubble — made it possible to measure galaxies’ distances from Earth with unprecedented accuracy. And in 1998, two teams of cosmologists discovered that the expansion of the universe is accelerating.

This soon gave rise to the idea of dark energy. And before long, cosmologists modified the big bang theory to include inflation, an incredibly brief moment of ridiculously fast space-time expansion.

These are extraordinary claims, and — as Neil DeGrasse Tyson has said — extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. But is there any?

You’d be surprised. And it all comes down to the CMB, the cosmic microwave background radiation.

You might recall from recent-ish posts that the CMB is the afterglow from recombination, when the atomic nuclei of the early universe were able to capture and hold free-floating electrons for the first time ever.

It’s the farthest we can see in the universe (and back through time). Before recombination, the universe was opaque, so trying to peer through the CMB is like trying to see through a blackout curtain.

The CMB is, in effect, sort of a cosmic fossil. A moment frozen in time.

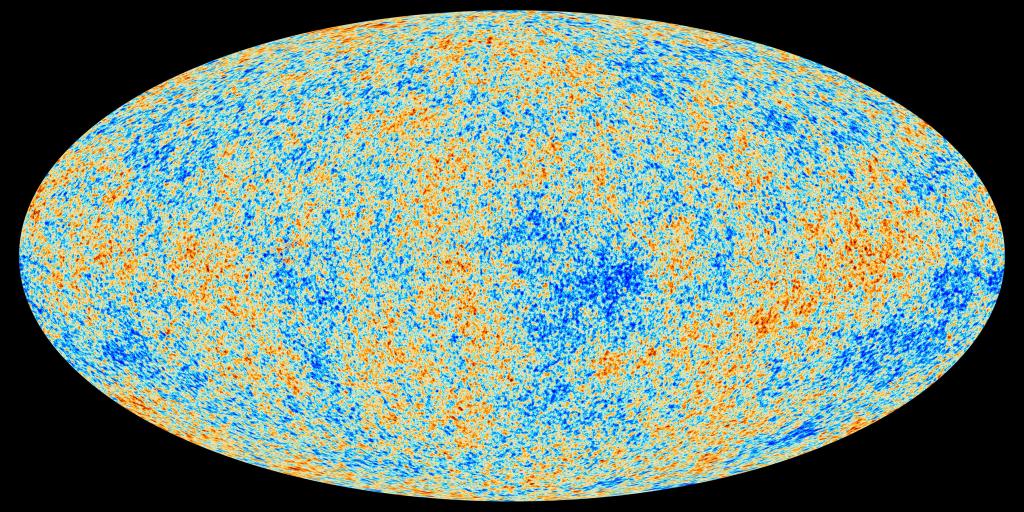

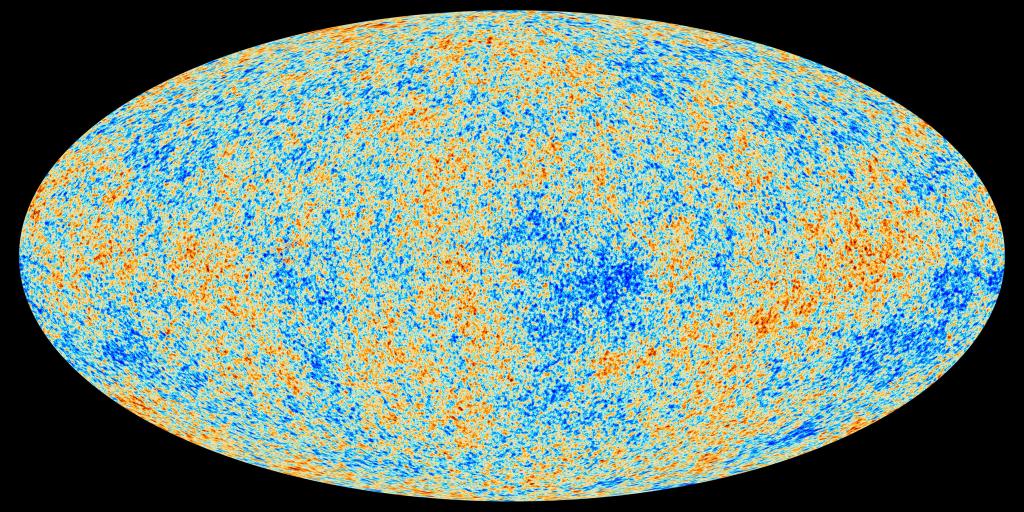

Here it is, in the farthest reaches of our observable universe, just beyond the dark ages:

Now, remember in earlier posts, when we said that the CMB is isotropic — that is, it looks almost exactly the same in all directions?

When we covered the cosmological principle, I also mentioned that the CMB isn’t exactly isotropic. There are minor variations.

We can bring out those variations by taking the average of the intensity of the CMB across the entire sky, and then subtracting that average, leaving only the irregularities that deviate from the average.

What if I told you…

…that those irregularities are sound waves?

Yeah, I know what you’re thinking. Sound doesn’t travel in space! Science fiction movies tend to imply that it does for dramatic effect, but that’s just a common misconception…right?

Right. But that’s because sound waves must travel through some type of medium (material). They can’t travel through a vacuum.

At the beginning of time, the universe’s scale was tiny, but it was full of the same amount of stuff that exists today. It was dense enough that sound waves could travel.

The Big Bang made a sound.

As a matter of fact, I found a video that approximates it. Note that the actual sound would’ve been far too low for humans to hear by about 50 octaves, but this video multiplies the frequency by 1026 so that it is audible.

Now, we can verify the predictions made by the inflation-modified big bang theory.

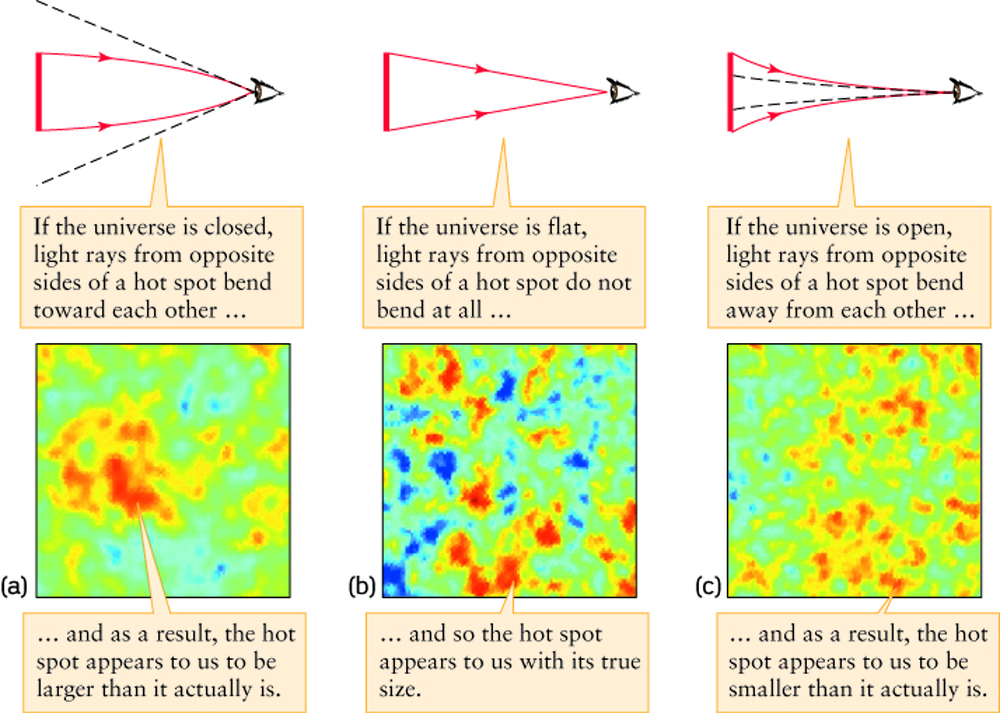

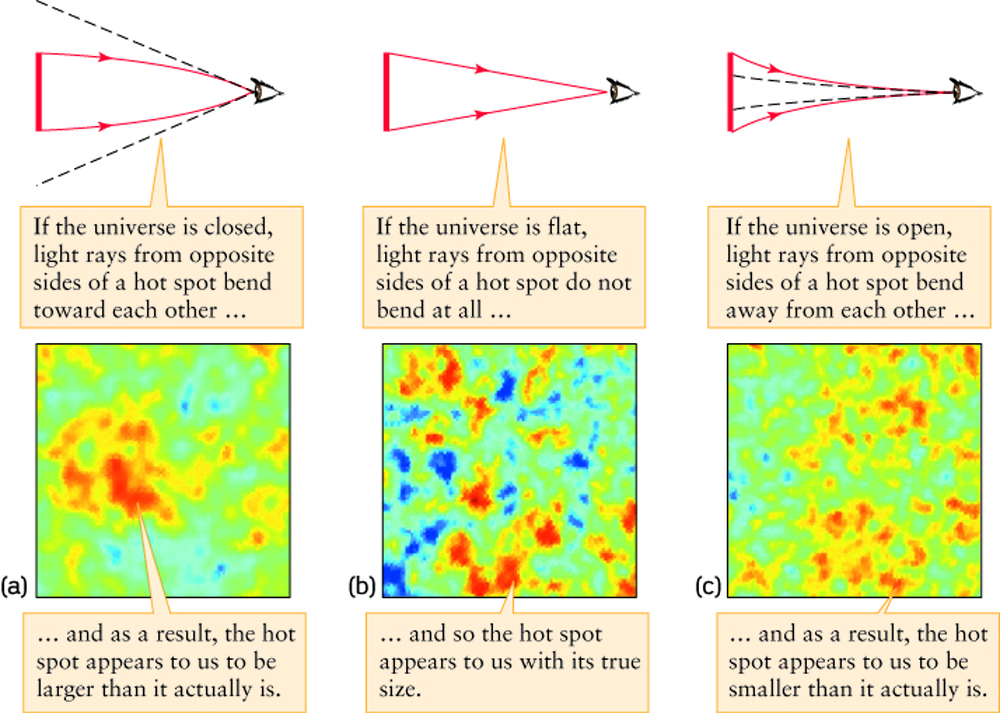

Depending on the shape of the universe — positively curved (closed), flat, or negatively curved (open) — the variations in the CMB will appear differently:

Inflation predicts that the universe must be flat. And this is very important to verify, because it shouldn’t be.

To be flat, the density of all matter and energy in the universe must exactly equal the critical density: 9 x 10-27 kg/m3.

But as we discussed in my last post, this isn’t a value the universe should naturally tend toward. It’s a sweet spot, like perfectly balancing a teeter-totter.

First, though…what’s inflation, again?

According to the modified big bang theory, inflation occurred 10-36 seconds after the Big Bang, when the electroweak force disconnected from strong force (as I explain here).

This separation of two of the fundamental forces of nature unleashed an insanely powerful burst of energy — which caused the universe to inflate in size by a factor of at least 1050 over the course of only 10-32 seconds.

Inflation makes specific predictions about the sizes of the variations in the CMB. We can then compare these predictions to the observable sizes.

So, what do the sizes of those variations say about the shape of the universe?

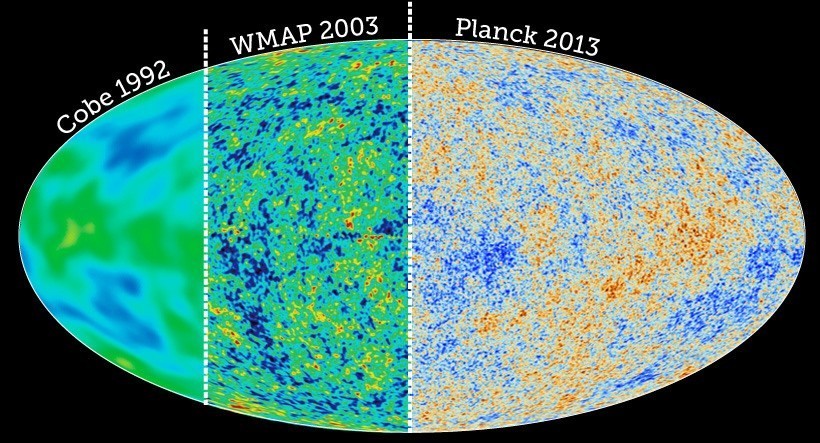

In order to test the inflationary hypothesis, we need to measure the sizes of the smallest variations. And in the years between 1992 and 2013, satellites and space telescopes have been able to yield increasingly precise results.

In 2003, the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) was able to make extensive measurements of the spatial distribution of the CMB. You might be more familiar with the Planck space telescope, which launched with the same mission in 2009.

Using math that’s beyond me at this point in my schooling, cosmologists calculate that if the universe is flat, the most common diameter of CMB irregularities should be about 1°. A positively curved (spherical) universe would have larger irregularities, and a negatively curved (saddle-shaped) universe would have smaller irregularities.

As it turns out, the variations fit predictions very well for a flat universe.

Not sure how the prediction looks similar to data? For one thing, the prediction is a very rough illustration. But note that in both the flat prediction and the data, the red splotches are about the same size and just as common as the blue splotches (unlike the negative/open prediction), and on the whole, all the splotches are small (unlike the positive/closed prediction).

If the universe is flat, then its density must equal the critical density. But is that what we observe?

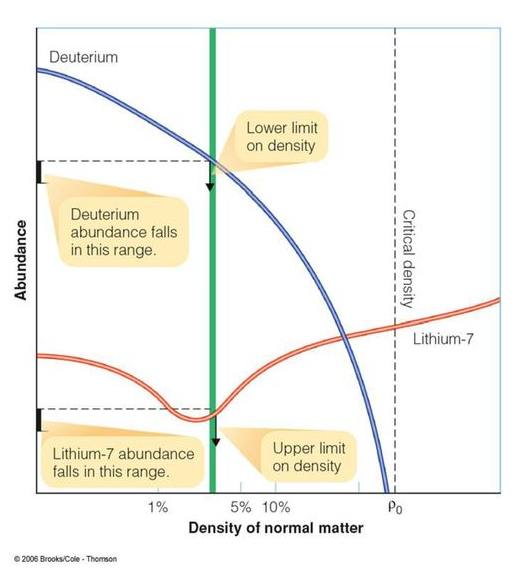

Now, remember when we used the relative abundances of deuterium and lithium-7 to measure the density of matter (baryonic) and energy in the early universe?

As you may recall, this graph measures relative abundance as a percentage of the critical density (the dotted line).

The lines for lithium-7 and deuterium are a plot of what the abundance of each element would be for each density on the horizontal axis scale.

We found that lithium-7 places an upper limit on the possible density of normal (baryonic) matter, and deuterium places a lower limit, leaving us with a very small range of possibilities (the width of the green band).

We then ran into a problem: as you can see, that green band is nowhere near the critical density.

Dark matter outweighs baryonic matter by a factor of between 5 and 10…

…but, added to baryonic matter and energy, it still only brings the density of the universe to about a third of the critical density.

In 1998, cosmologists discovered that the expansion of the universe was accelerating. They then hypothesized the existence of dark energy: a mysterious antigravity force that is driving the expansion.

In theory, dark energy can make up the missing density, because it’s still energy and E=mc2 means it is equivalent to some amount of matter (as I explain here). But is it true?

Here’s the crux: the WMAP data confirms the density of the universe independently of the element abundances.

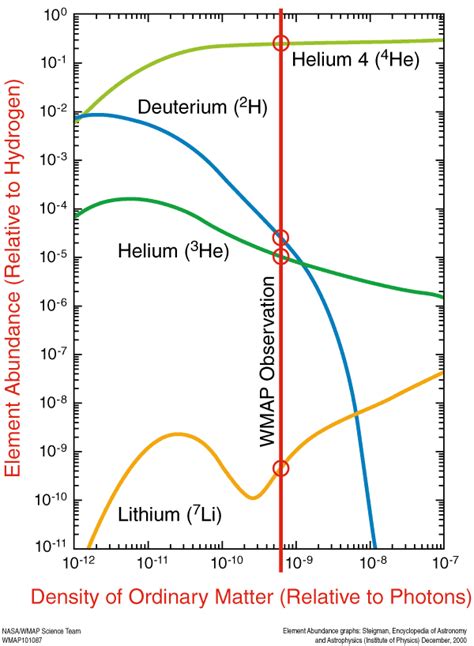

This graph doesn’t chart the abundances as a percentage of the critical density, but rather as a density relative to photons (remember that E=mc2 means that photons — a form of energy — are equivalent to matter and can have a density).

While we can’t compare these two graphs based on the way they measure the density of baryonic matter, we can just look at the shapes of the lines, particularly that of lithium-7.

The data lines up exactly. WMAP confirms that the density of ordinary matter is what it must be if our calculations based on lithium-7 are correct.

And, in fact, there’s even more data in the CMB…

This graph plots the different sizes of the splotches in the CMB. And the details of this curve reveal an absolute crap ton…

The universe is flat, accelerating, and will expand forever.

The age of the universe is 13.8 billion years.

The universe contains 4.5% baryonic matter, 22.7% dark matter, and 72.8% dark energy. All forms of energy are included within these percentages. Dark energy — whatever the heck it is — does exist, and brings the density of the universe to the critical density.

The Hubble constant (which I covered in my first post on the Big Bang) is 70 km/s/Mpc.

Inflation is accurate.

Dark energy is likely described by the cosmological constant, though quintessence (covered briefly in my dark energy post) is not ruled out.

Hot dark matter is ruled out; only cold dark matter could have clumped together rapidly enough to explain observations of galaxy clusters and superclusters.

And that, people, is a truly mind-blowing collection of (relatively) firm facts. Yes, cosmological research is still evolving, and details are still being nailed down. But our foundational understanding is amazingly solid.

(How does the data say all that? It’s in the math — math that is beyond me at this point in my schooling. I’ll get there soon enough — and explain it on this blog!)

But what if I told you it doesn’t stop there?

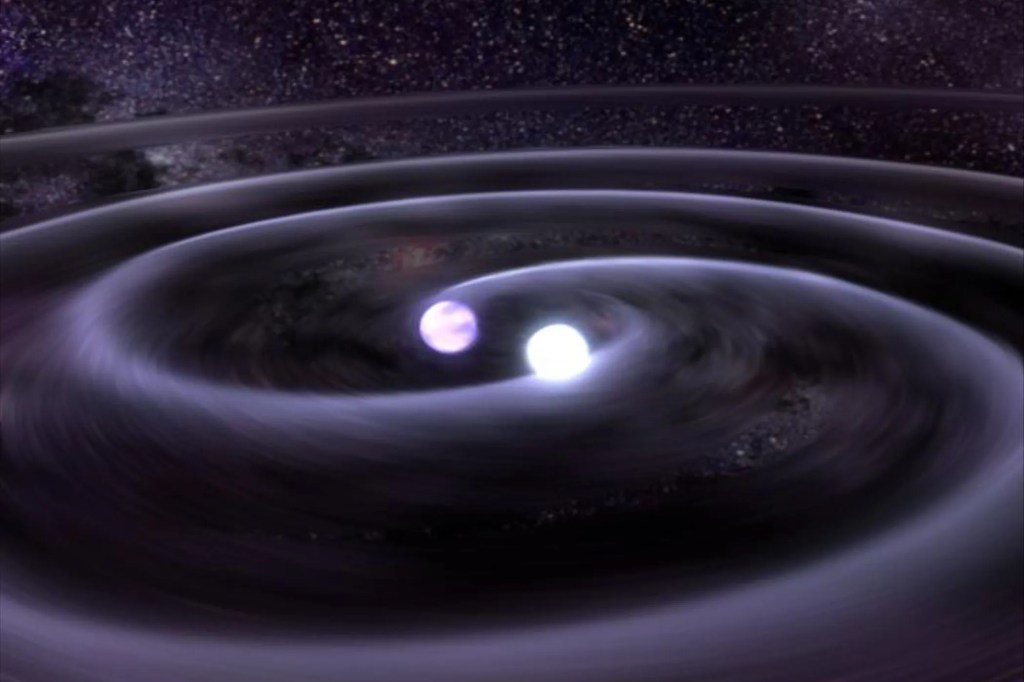

There’s one other prediction the inflationary hypothesis makes: gravity waves.

Yeah. Gravity waves.

Have you heard of these guys?

These are literal ripples in the fabric of space-time, emanating outward from moving objects like ripples in a pond. And their detection is one of the more recent marvels of modern astrophysics.

Before we could directly detect gravity waves, though, we could observe their effects on the CMB.

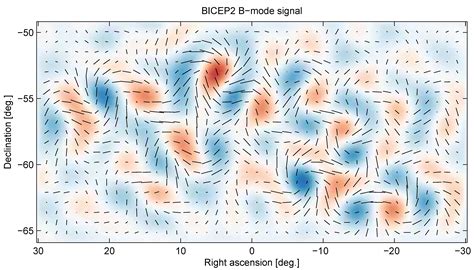

Inflation would have produced density variations in the gas of the big bang that, for some reason beyond my current understanding, would have had twists like a corkscrew.

At the moment of recombination, photons in the primordial universe would’ve scattered off the electrons in the gas and ended up with a corresponding twist called polarization.

(Don’t ask me how that works…it’s another thing that’s currently beyond me.)

Anyway…cosmologists are still on the hunt for a polarization signature in the CMB. In 2014, a research team thought they’d found it…

…but in 2015, the data was reexamined, and it turned out the polarization signature was just a result of interstellar dust.

To be clear, inflation is still the leading hypothesis. We just don’t have a “smoking gun” dramatically confirming it yet.1

Scientists gain confidence in their hypotheses when prediction matches observation. Astronomy is a challenging branch of science in that we sometimes need to modify our approach; we can’t conduct tests in a laboratory the traditional way.

Throughout this blog, I’ve tried to thread in the general theme of how astronomers piece together evidence from across the night sky to form a concrete, sequential picture.

Cosmology is the ultimate push to understand that picture. The gathering of evidence to piece together the grandest story in cosmic history: that of the universe itself, from beginning to end.

The concepts cosmology uncovers are so “astronomical” — so to speak — that you might expect it to be the most elusive of science branches. And in some ways, it is; we still have yet to puzzle out the nature of dark matter and dark energy. 95% of the universe is a mystery.

But thanks to the cosmic microwave background radiation and its surprisingly plentiful data, we understand cosmology more firmly than we ever expected to.

The story’s not over, though. Since this is such an intensive subject, I plan to spend a few posts covering some broader review of cosmology. Soon enough, we’ll move on to the planetary sciences!

- A previous version of this post neglected to clarify that the 2014 polarization signature was later reexamined and cast into doubt. My textbook was written shortly after the signature was discovered, and presumably the writers were unaware of any correction to the research. I myself was unaware until I attended a presentation by one of the original researchers some time after I’d published the post. ↩︎

Did I blow your mind? 😉