Have you ever wondered how the heck astronomers think we know anything about cosmology?

It’s a truly mind-blowing field of study, full of whacky concepts like the shape of empty space, the expansion of the universe, and dark energy. More than that, it takes on the lofty goal of telling the story of the whole universe, from beginning to end.

It’s totally natural to wonder if we can really be sure of our understanding.

If you’re a total newbie, this post is for you. I’ve deliberately tailored it so that you need very little background knowledge. It’ll help to have read some of my older posts on certain fundamentals (linked here where relevant), but you don’t need to.

We’re going to cover the four bedrock observations that give cosmologists confidence in our current understanding of the universe.

- Expanding Universe: the Hubble Law

- Big Bang: the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation

- Composition of the Early Universe: Stellar Compositions

- Dark Energy: Acceleration

Expanding Universe: the Hubble Law

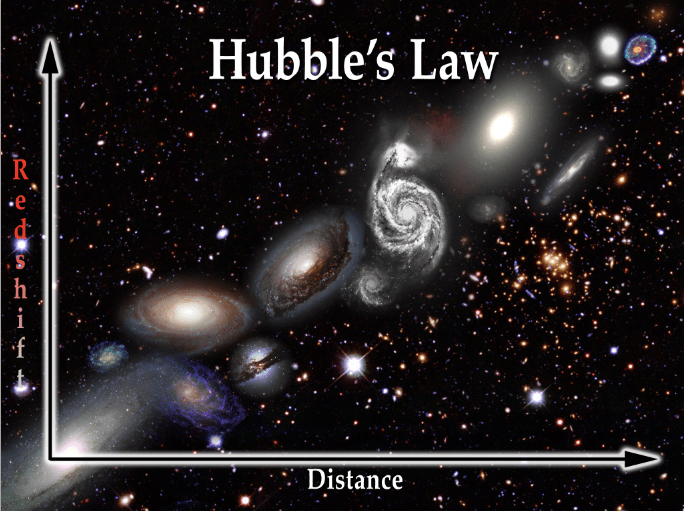

The Hubble Law is a way to estimate the distance to any galaxy. But the key lies in how it works.

It uses redshift.

Redshift is a somewhat advanced concept, but what’s important for this post is that when an object is moving away from you, it will appear redder than its true color. The amount of redshift depends on the speed of “recession” (the speed it’s moving away from you).

In general, this is known as a Doppler shift. But Doppler shifts don’t explain these particular redshifts. These are cosmological redshifts.

(Note that you can’t tell what direction a star in the sky is moving just based on its color. I explain why here.)

In 1929, Edwin Hubble discovered that galaxies’ redshifts were directly proportional to their distance from Earth. In plain English: a nearer galaxy has a small redshift (appears less red, closer to its true color) and a distant galaxy has a large redshift (appears very red).

But, as we noted above, redshift tells you how fast an object is moving away from you. Why would that be directly related to a galaxy’s distance? (Why can’t we have, say, a very distant galaxy that’s moving slowly?)

The Hubble Law is bedrock evidence that the universe is expanding.

Specifically, the space between galaxies is expanding.

Galaxies that are very distant from one another have more space expanding between them than galaxies that are closer together. So distant galaxies will be carried apart at a more rapid rate than galaxies that are near one another.

Big Bang: the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation

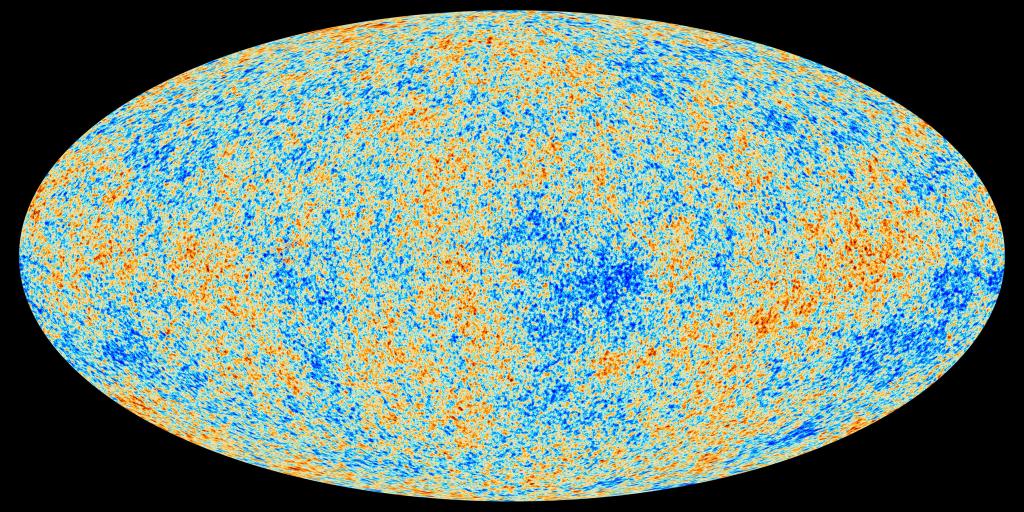

The cosmic microwave background, or CMB, is a particularly critical piece of evidence for two reasons:

- It was predicted decades in advance of its discovery.

- It contains a ton of advanced mathematical data that reveals way more detail than you’d expect about our universe’s story.

Making predictions and confirming those predictions with observations is foundational to the scientific method. Any time that predictions match observations, it gives scientists a ton of confidence in their understanding.

So let’s follow the timeline of how the CMB was predicted.

1939

Astronomers observe gas in the interstellar medium bathed in radiation from something with a temperature of 2 to 3 kelvins.

1949

Physicists Ralph Alpher and Robert Herman note that anything we can observe from shortly after the Big Bang would have a huge redshift. Any radiation we see from gas in the early universe would appear to us to have a temperature around 5 kelvins.

Mid-1960s

Bell Laboratories physicists Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson discover a background radio signal that comes from all over the sky.

1990

Satellite measurements confirm that this background radiation has exactly the shape of curve that Gamow predicted:

The apparent temperature of the background radiation is measured to be roughly 2.7 kelvins, close to Alpher and Herman’s 1949 prediction (and matching the 1939 interstellar medium observation).

In essence, physicists made predictions based on theories of the Big Bang, and the CMB confirmed those predictions.

And, like I said above, the CMB also contains a load of detailed data about the early universe. This data has confirmed and clarified many of the more advanced theories in cosmology.

Composition of the Early Universe: Stellar Compositions

Theory predicts that, 3 minutes after the Big Bang, the universe was made up of roughly 75% hydrogen, 25% helium, and trace amounts of lithium.

(To find out why, read my post on the first nucleosynthesis!)

When stars first began to form, that is the mixture of stuff they would have formed from. So, if we can study the compositions of the oldest stars, we can discover a snapshot of the composition of the early universe.

By nature, stars fuse atomic nuclei in their cores. That’s how they remain stable. Over the course of a star’s lifespan, it will fuse hydrogen nuclei to create helium nuclei, and so on and so forth. This changes the atomic makeup of their cores over time.

But fortunately for us, the composition of a star’s atmosphere does not change. And that just happens to be the easiest part of a star to observe (using stellar spectra).

Observations of the oldest stars’ atmospheres reveals almost exactly the composition we would expect:

Their atmospheres are made up of 75% hydrogen, 25% helium, and trace amounts of lithium. That’s the same composition we theorized for the early universe. So, observation matches prediction.

This doesn’t just confirm the composition of the early universe, though. It gives astronomers confidence in the theories of why that would be the composition, because those theories led to an accurate prediction.

And last but not least…

Dark Energy: Acceleration

Perhaps the most important cosmological theory to confirm is that of the universe’s most elusive concept: dark energy.

Dark energy is a catch-all, placeholder term for something we don’t understand. So, why do we think it exists?

The evidence lies in observations of type 1a supernovae, a type of distance indicator.

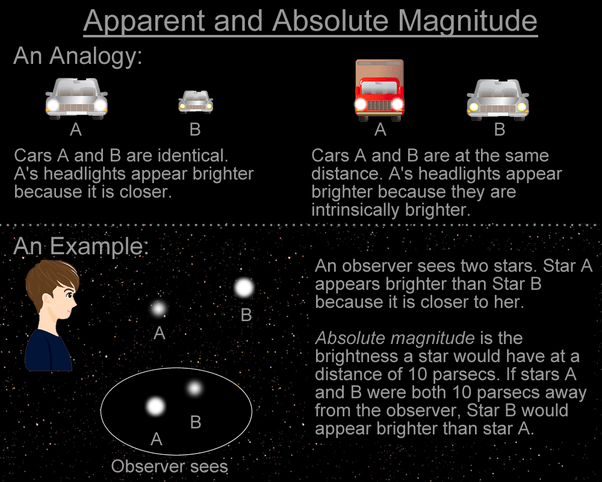

For this post, all you need to know about type 1a supernovae is that they are a type of supernova that always reaches the same peak brightness. That’s important because, when you look up at a bright star in the sky, you don’t know if it’s truly quite bright — or if it just appears bright because it’s quite close to us.

But type 1a supernovae always reach the same peak brightness. If we observe them in a distant galaxy, we know how bright they are. We can then figure out how distant they are based on how bright they appear in our sky.

Remember that we can also estimate the distances to galaxies using the Hubble Law.

Here are “before” and “after” frames of type 1a supernovae in distant galaxies. Each column shows two images of the same galaxy. The bottom images show the galaxies before or after the supernova has occurred. In the top images, you see an extra point of light that’s not there in the bottom images: that’s the supernova.

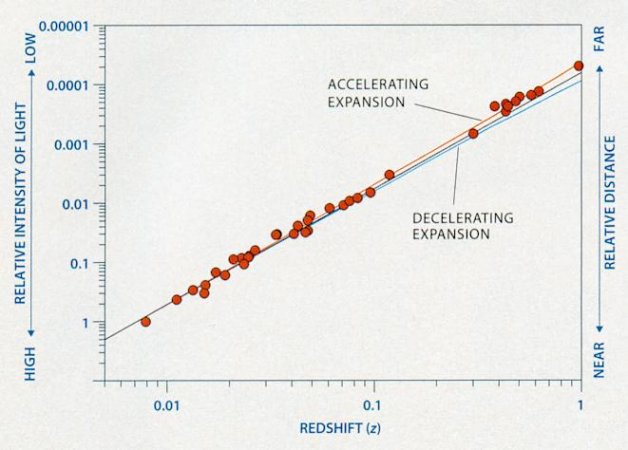

In 1990, two competing research teams observed that supernovae in distant galaxies were fainter than expected.

That is, the galaxies were farther away than the Hubble Law said they should be.

Remember that the Hubble Law is bedrock evidence for the expansion of the universe. But if these galaxies were more distant than the Hubble Law predicted, then the space between us and them had expanded faster than expected, carrying them apart from us more quickly than expected.

That could only mean one thing: the expansion of the universe is, in fact, speeding up.

Observations of even more distant supernovae later confirmed these results. The expansion of the universe is accelerating.

According to Einstein’s theory of general relativity, gravity works by literally curving the fabric of space. So, gravitation between galaxies should alter space itself and slow down the expansion…unless there is some kind of force of repulsion that can counteract gravity.

That’s where the idea of “dark energy” comes from.

And there you have it, people — the bedrock evidence supporting our current understanding of cosmology. I hope I’ve managed to simplify this as much as possible! If you have any questions, please do let me know and I’ll do my best to answer.

Next up, we’ll round up and summarize what we know so far about dark matter.

Leave a reply to Emma Cancel reply