Have you heard of the Messier Marathon?

If you travel in astronomy circles, you’re bound to have heard of it around this time of the year. Every March and April, astronomers from across the northern hemisphere embark on a challenge: observe all 110 objects from the Messier catalog in one night.

But…why?

I mean, beyond the fact that it’s fun — why that particular catalog? Why March and April? Why just the northern hemisphere? And how is it possible to view them all in one night?

And — bonus — can you do it, too?

Well, spoilers for that last one — the answer is yes! But read on to find out the rest!

Alright, let’s tackle those questions one by one.

- Why the Messiers?

- Why just the northern hemisphere?

- How is it possible to view them all in one night?

- Why March and April?

- How can you do the Marathon?

Why the Messiers?

This question takes us back to the history behind the Messier catalog.

I’ve written about it a little before, in my broader post on how deep-sky catalogs work. But here’s a little refresher…

First things first: the Messier catalog was never intended to be a comprehensive catalog of deep-sky objects.

The guy who compiled it, Charles Messier, was on a hunt to discover a new comet. His problem was that, with the technology of the time, a lot of deep-sky objects — like star clusters and galaxies — look a lot like comets.

Here are a pair of comets, detected while distant from the Earth:

They’re the little white smudges in the yellow circles.

Now, for comparison, here’s a globular cluster:

See how they look a bit similar?

An experienced astronomer can tell the difference, even at these faint magnitudes…but it’s a lot easier if you know what to expect. That is, if you know which one is a globular and which one is a comet, the differences suddenly jump out at you as visually obvious.

If you’re trying to discover a comet that’s never been cataloged before, you’re going to be pouring over tons of night-sky images like this…and all of them might be globulars or faint galaxies, or some of them might be comets.

So, how do you definitively tell the difference?

Here’s the key…

Objects in the solar system move relative to the background stars. Deep-sky objects do not.

For example, here’s the path Mars takes across the night sky:

(Don’t mind that little zigzag in the middle — technically known as a retrograde loop. I explain this in my post on the Copernican model of the solar system.)

In this image, you see the constellations labeled like regions of a map. Indeed, that’s how astronomers use the constellations — as a literal map of the night sky. (And boy does that take us back, to the earliest posts on this blog…)

Now, notice that Mars traverses the entire image. It spends some time in multiple constellations — Aquarius, Pisces, Ares, and Taurus.

A deep-sky object, on the other hand — a star cluster, nebula, galaxy, etc. — will always stay in the same fixed position relative to the stars.

Comets are solar-system objects. So, all you have to do to differentiate between a comet and deep-sky object (or DSO) is track it night to night, and see if it moves.

That was the purpose of the Messier Catalog. As he observed object after object, he noted down the ones whose positions stayed fixed. 110 of these were cataloged as the Messier objects.

Still, that doesn’t quite answer our question — why does the Marathon involve this particular catalog?

To answer this, let’s turn to another question:

Why just the northern hemisphere?

Because Charles Messier lived in Paris, France, and he observed all the objects from there.

Remember what I said about the Messier catalog not being a comprehensive DSO catalog?

Yeah…it’s biased in favor of the northern hemisphere.

To be fair, not all of the northern hemisphere can see them all, either. The best latitudes to see all the objects are between 20°S and 55°N. But that still includes a lot of north and not a lot of south.

Now you can begin to see why it’s the Messier Marathon, and not some other deep-sky catalog. The Messier catalog is unique in that, if you live in the right latitudes, all of the objects will be visible to you at some point during the year.

Next question…

How is it possible to view them all in one night?

We’ve partially answered this already: at the very least, we know that all the objects are possible to view without, ya know, booking a flight to a different hemisphere. That trip would definitely eat up the one-night viewing session.

But as you may know, constellations change with the seasons, and so too do the DSOs in those constellations. For example, Sagittarius and its rich array of globular clusters is best viewed during the summer. But Orion, home to the Orion Nebula, is best viewed in the winter.

Both Sagittarius and Orion are home to Messier objects. In fact, the Orion Nebula is one of them, designated M42.

So how can we see them all in one night?

Well, to start…it’s not really about the seasons, so much as Earth’s location in its orbit.

Take a look at the two example locations on Earth’s orbit shown above, one in June and one in August.

In June, the Earth is positioned on the other side of the sun from Taurus. To look in the direction of Taurus, we have to stand on the daylight side of the Earth. And we can’t see stars during the day. The sun is too bright.

Likewise, in August, the sun is between Earth and the constellation Leo…so Leo “appears” in the daytime sky, and is not actually visible.

Notice that none of the constellations are limited to being viewed in only one season. They’re only limited to not being viewed — for one specific month of the year.

So, if we can find a constellation that doesn’t have any Messiers, we can see the rest of the sky during the month that constellation is hidden behind the sun.

Now you can probably figure out the answer to the next question…

Why March and April?

Because, while there are technically Messiers in all the constellations along Earth’s orbit, there is a constellation-sized area of the sky in the path of Earth’s orbit where there aren’t any.

That region is smack-dab between Pisces and Aquarius…which is where the sun appears during March and April.

So, the tail end of March and beginning of April is the best time to view all the Messiers in one night. As the Earth turns through the night, the entire sky — save for that little nook between Pisces and Aquarius — will pass overhead.

Now for the million-dollar question…

How can you do the Marathon?

Step 1: Choose a time as close as possible to the new moon. That way, the light of the full moon won’t interfere with your dark sky. In 2025, the best date is March 29.

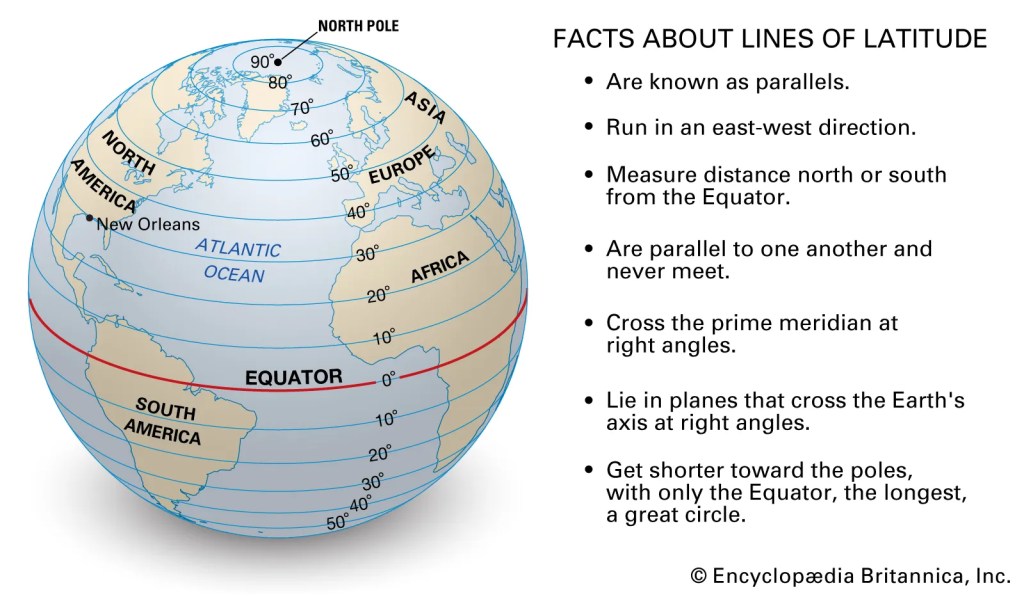

Step 2: Make sure you’re in the northern hemisphere between 20°S and 55°N latitude.

Step 3: Rest assured that Charles Messier had only a 4-inch refractor — you don’t need crazy gear to do the Marathon! You don’t need any equipment better than what he had.

Step 4: Take advantage of the apps available in the modern era. I’ve found Stellarium and Sky Tonight to be quite helpful.

I highly recommend Stellarium as a general star chart app; it has a comprehensive collection of DSOs, including the full Messier, NGC, IC, and Caldwell catalogs. (Fair warning: the free version is quite limited, but the paid version is just a one-time fee of like $20 or something.)

As a star chart app, I don’t recommend Sky Tonight. But that’s not what it’s meant for. It is quite literally meant for the Messier Marathon.

If you’re going to squeeze in all 110 Messier objects, you need to be strategic: start observing as soon as it’s dark enough, and view them in the right order. Over the course of the night, all these objects will travel westward across the sky. You need to snag each one before it sinks below the western horizon.

Sky Tonight lets you set alerts for the Messiers’ rise and set times, and it lets you know exactly when “astronomical twilight” begins — when it’s dark enough to start viewing.

Which brings me to Step 5…

Plan ahead!

For your convenience, I’ve compiled a list of all 110 Messiers, listing the type of object, the constellation, and the right ascension and declination coordinates. You should be able to save, print, or download this file.

Note that there’s some confusion surrounding M102. Its original discoverer has stated that it is a duplicate observation of M101, but NASA considers it to be the same object as NGC 5866 from the New General Catalog. I’ve gone with NASA on this one. The description and coordinates listed in the table above are those of NGC 5866.

(Keep in mind that I manually compiled this in about an hour, and by the time I was done, my brain was a bit fried…so there could be minor errors. I’ll correct any that I find1.)

…and that’s it!

Yup — it really is that simple. It takes planning, and it’s not easy, necessarily, but with the right resources the Messier Marathon is quite accessible to beginners.

I’ll leave you with a fun visualization I found…

This “periodic table” groups objects of the same type in rows, with the first row indicating a more northern position in the sky and the second row indicating a more southern position. The table is organized from left to right by the objects’ right ascension coordinates.

Anyway. That’s enough chatter from me — I’ll let you get to planning your marathon! 😉

- M23 was missing RA/dec coords, and the coords for M21 and M20 were incorrect. This has been updated. ↩︎

Leave a reply to Ggreybeard Cancel reply