Einstein’s theory of general relativity holds that matter curves the fabric of space-time. That’s how gravity works.

In turn, that gravity shapes the fabric of the universe.

Depending on how much mass is in the universe, gravitation can curve the fabric of space back on itself, curling the universe into a ball.

We also know that since the Big Bang, the universe has been expanding. And just as gravity shapes the fabric of space-time, it should also slow that expansion.

But there’s a problem…

The expansion of the universe isn’t slowing down.

In fact, it’s accelerating!

But…wait. How do we know?

This story begins in the 1920s, when Edwin Hubble first discovered that the universe was expanding.

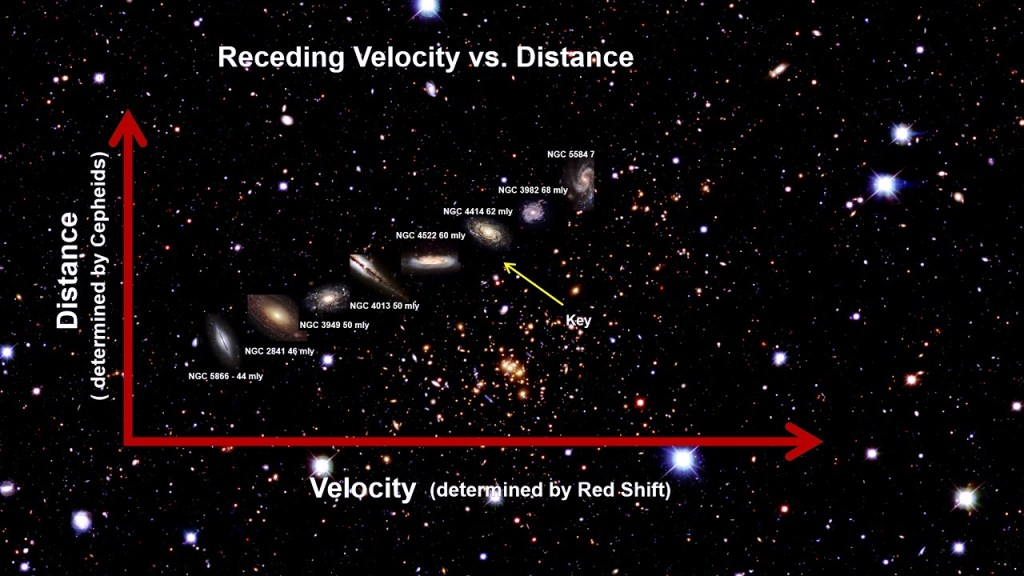

Hubble was measuring the distance to the nearest galaxies using Cepheid variable stars as a distance indicator. And he realized that the galaxies’ redshifts were proportional to their distance.

These weren’t Doppler redshifts, though. Astronomers would soon realize that these were, in fact, cosmological redshifts — redshifts due to expanding space stretching light into longer wavelengths.

This relationship between distance and redshift became known as the Hubble Law.

Einstein had published his theory of general relativity quite recently at the time, in 1915. When the Hubble Law was discovered, astronomers understood that it meant the universe was expanding.

Redshifts are a measure of an object’s recessional velocity — that is, the speed at which it’s moving away from us. In this case, it’s the speed at which expanding space is carrying galaxies apart. And if that expansion is slowing, then that velocity would be decreasing.

Astronomers understood that they should be able to detect the slowing of the expansion in those same redshifts. And they spent decades trying to make accurate measurements.

This wasn’t easy. After all, they needed to accurately measure the redshifts of very distant galaxies, and ground telescopes can only resolve so much detail.

But in 1990, a space telescope named for Edwin Hubble was launched. And the Hubble Space Telescope changed everything.

You might remember from my post on the Hubble Law that it can be used as a shortcut to finding a galaxy’s distance. But it’s not a distance measurement — it’s a velocity measurement. It only works to measure distance if we assume the recessional velocity is constant.

If we’re trying to detect a change in distant galaxies’ recessional velocities, cosmological redshift no longer gives us their distance. We need to find the distance some other way.

So, a pair of competing research teams began calibrating type 1a supernovae as distance indicators.

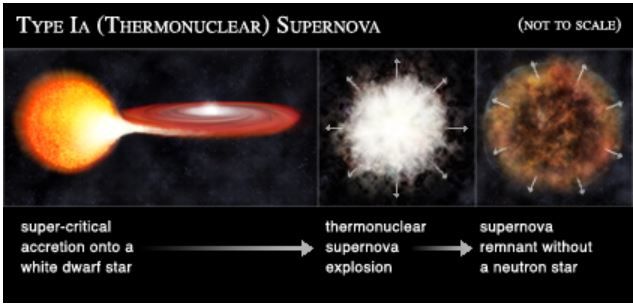

Type 1a supernovae are the single most reliable distance indicator. And that’s because they always reach exactly the same peak luminosity.

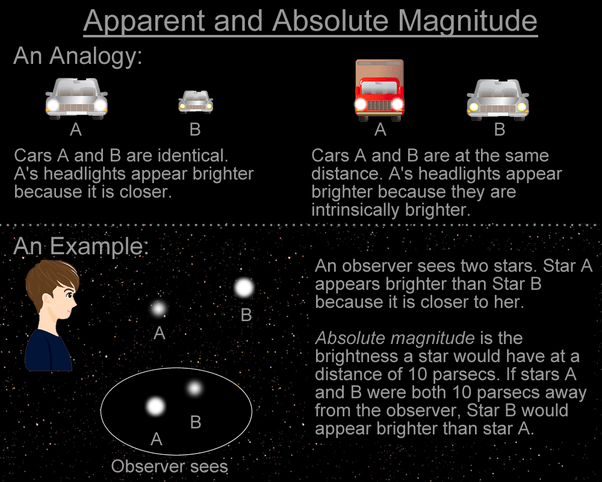

When you look up at a bright star in the sky, you don’t know if it’s truly quite bright, or if it just appears bright because it’s quite close to us:

If you can discover the actual distance to a star, you can calculate its intrinsic brightness — that is, how bright it actually is.

But we don’t need to worry about that with type 1a supernovae. They are always produced when matter falling onto a white dwarf surpasses the Chandrasekhar limit of 1.4 solar masses and causes a nova explosion.

So, every single type 1a supernova will be similar, and they will always reach the same peak luminosity. If we spot one in a distant galaxy, we know how bright it is.

There’s another thing that makes type 1a supernovae the most reliable distance indicator: they’re really freaking bright.

Unlike fainter distance indicators like Cepheids, they can be observed in very distant galaxies — the very galaxies whose recessional velocity we need to measure.

This graphic shows five images of distant galaxies. In the bottom row, you see them with no nova occurring. But in the top row, you see a new, bright flash of light — a type 1a supernova.

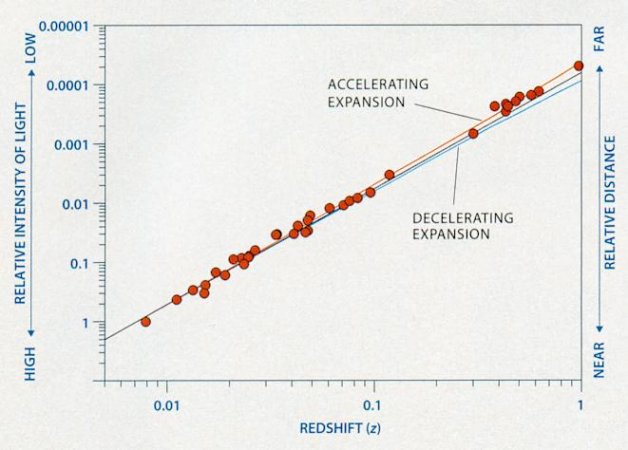

The two competing teams observed these supernovae with a particular range of redshifts — that is, within a particular range of expected distances.

If the expansion of the universe was slowing, the supernovae should have appeared brighter than expected, given their redshifts. That is, they should have appeared closer to us than the Hubble Law says they are. But they weren’t.

They were fainter.

In other words, they were farther away than the Hubble Law said they should be.

That could only mean one thing: the expansion of the universe is, in fact, speeding up.

And that doesn’t make much sense at all.

For the expansion to accelerate, there must be some force of repulsion that can counteract gravity. That’s an exciting claim — but it was also totally unexpected, and needed to be checked.

Some astronomers wondered if the type 1a supernovae had been measured inaccurately. But even more distant supernovae were later observed and confirmed the initial measurements.

Then, astronomers found more evidence of the accelerating expansion.

The Two-Degree-Field Redshift Survey mapped the position and redshift of 250,000 galaxies and 30,000 quasars — that is, an erupting supermassive black hole in the core of a very distant galaxy.

What you see above is a negative image: an image where bright objects like stars and galaxies are depicted as black, and space is white. Astronomers often prefer to deal with negative images because it makes it easier for our eyes to pick out small details in the observations.

The black smudges you see here are superclusters of galaxies — large aggregations of galaxy clusters. As expected, the Two-Degree-Field Redshift Survey revealed that these superclusters were arranged in filaments — that is, the long chains of superclusters that are the largest structures in the universe.

That’s these guys, by the way. Filaments form a vast cosmic web, caused by gravitation from dark matter.

But more than that, this survey confirmed that the expansion of space-time was, in fact, accelerating.

(Don’t ask me how they did this — this one’s beyond me at this point in my schooling. I know that it involved “a statistical analysis of the distribution of galaxies,” as my textbook states, but that’s Greek to me!)

Anyway.

This confirmation of the accelerating expansion of space was independent of the evidence from type 1a supernovae, and that gave astronomers a lot more confidence in the results.

Apparently, the expansion of the universe truly is accelerating.

And that brings us to quite possibly the biggest question in the history of astronomy…

What the heck is causing it?

Next up, we’ll explore what we know about the most mysterious force in the universe: dark energy.

Leave a reply to Emma Cancel reply