I considered titling this post “Dark Matter Demystified” and including it in my “Cosmos Demystified” series…but honestly, there are some promises I can’t make!

Dark matter is one of the most mysterious concepts in cosmology, second only to the even more elusive dark energy.

By far the weirdest thing about it is that, according to theory, it seems critical to explaining our observations of the universe. And yet, we’ve been unable to figure out what the heck it is.

I can’t “demystify” dark matter for you, because even the greatest scientific minds of the century don’t understand it yet. But I can round up and summarize what we do know about it.

So, let’s dive in, shall we?

- How was it discovered?

- Evidence in the Coma Cluster

- So…what could it be?

- Enter, stage left: gravitational lensing

- We also know that…

How was it discovered?

It’s a bit weird to say that dark matter even has been “discovered”…but what I mean here is, how did we first get clued in that it exists?

By measuring the rotation of galaxies.

There’s a very convenient phenomenon called the Doppler effect that lets us do this easily: the side of the galaxy rotating towards us emits bluer light, and the side rotating away emits redder light.

(If you’re curious about how that works, check out my post on the Doppler effect!)

But that’s when we run into a problem: the outer edges of galaxies rotate far faster than they should…at least for the mass that we can see.

Galaxies’ rotation is due to the stuff in them — stars, gas, dust — all orbiting the galactic center. And according to Kepler’s laws of motion, the stuff on the outer edges should orbit slower than stuff toward the center.

It doesn’t. Galaxies rotate largely as if they were solid disks, like frisbees.

We could easily explain that if the outer edges of galaxies were significantly brighter, indicating that there is more mass there and therefore more gravitation. But if there is, we can’t see it.

There is mass in the outer reaches of galaxies that we can’t see. And that is what astronomers have dubbed “dark matter.”

Of course, that’s not enough evidence to accept an extraordinary theory. But there’s more…

Evidence in the Coma Cluster

Meet the Coma Cluster: a cluster of galaxies whose intergalactic space — the vast emptiness between the individual galaxies — is filled with hot, low-density gas.

That’s normal for galaxy clusters. But the gas here is really freaking hot. So hot that it is observable in the X-ray range.

(For more on high-energy astronomy, check out my post here!)

If a gas is hot, that means its atoms — the building blocks of “stuff” — are moving very rapidly. And this gas is so hot that, according to Newton’s laws of motion, its atoms should have escaped the cluster altogether.

Unless an unseen mass of dark matter holds the gas captive.

So…what could it be?

Astronomers first wondered if “dark matter” was really just ordinary matter, but comprised of objects that are difficult to observe…such as black holes or neutron stars.

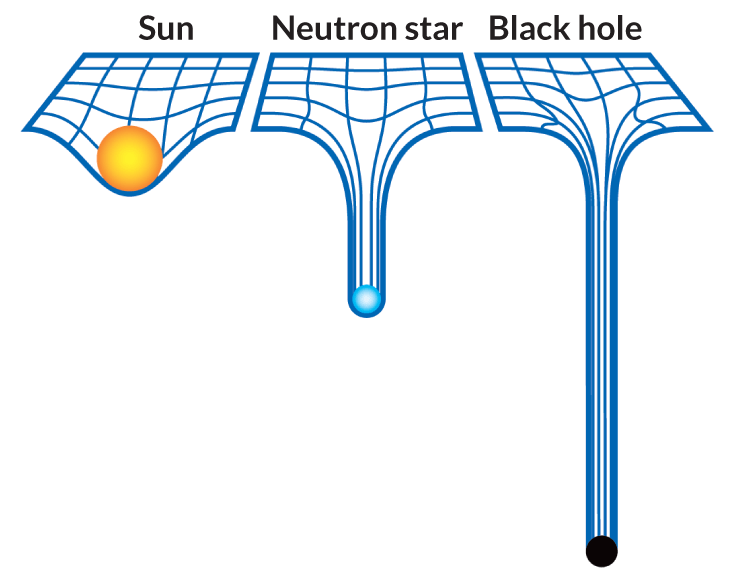

Both black holes and neutron stars have profound gravitational effects on the space around them, which makes them a good culprit for dark matter…

And for different reasons, they are difficult to detect.

Neutron stars are faint due to being ridiculously small (learn more about how luminosity relates to surface area here):

Seriously — a neutron star could fit in Los Angeles.

And black holes are difficult to detect because, by their very nature, they emit no light.

Well…sort of. For reasons that are beyond the scope of this post, black holes are actually detectable by their X-rays. And so are neutron stars.

Frankly, if the outer reaches of galaxies were full of enough black holes and neutron stars to explain dark matter, we’d notice that many X-rays. So that can’t be it.

What else could it be, then?

Thanks to Einstein, we understand gravity as a reaction of space-time to the presence of matter. That is, the fabric of the universe bends and deforms around matter (stuff).

Ordinary matter is known in sciency terms as “baryonic” matter because, at the teeny-tiny quantum-mechanical level, it is made up of particles called baryons.

So, we assume that dark matter must be made up of particles as well.

Quantum mechanics gives us a couple possible culprits in the form of axions1 and WIMPS (weakly interacting massive particles). But efforts to link any known particles to dark matter have been unsuccessful.

In short: Newton’s laws of motion are saying something is there that, by all accounts, really doesn’t appear to be there.

So…is it possible that Newton’s laws don’t describe reality as well as we think?

Enter, stage left: gravitational lensing

It’s a good question. But thankfully, there is yet another way to confirm dark matter’s existence.

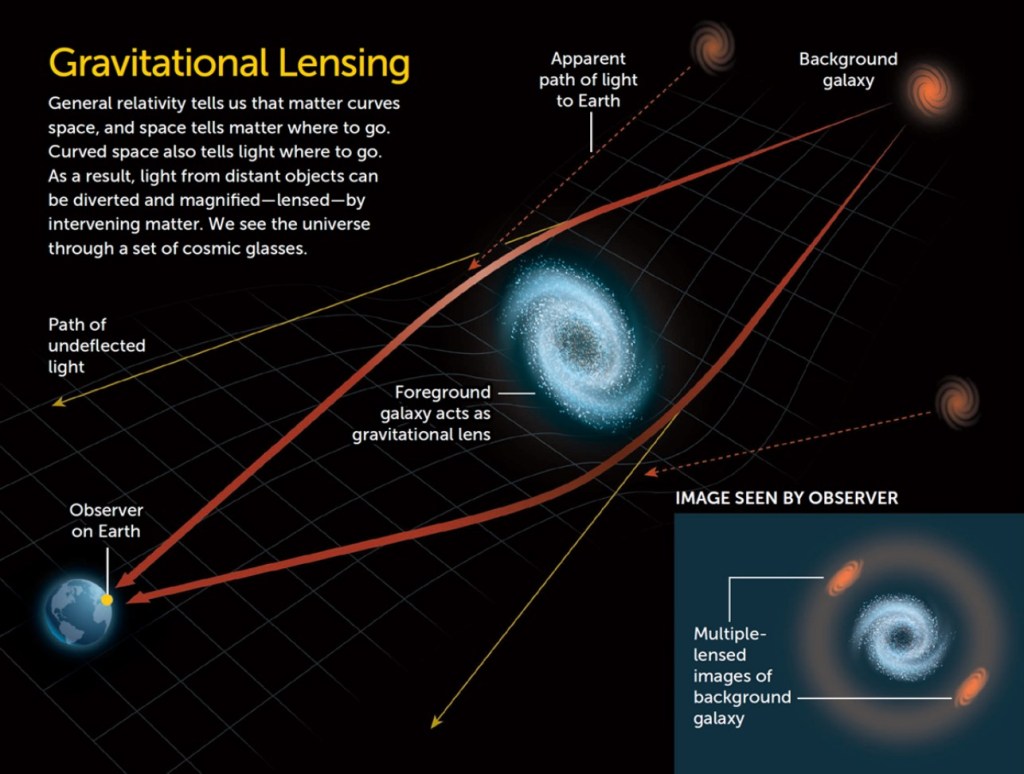

Gravity works because matter moves due to space-time curvature. But so does light — and that’s why gravitational lensing works.

Bent space-time literally bends and redirects light emitted from distant objects. It’s very useful for observing extremely distant galaxies that are too faint to observe directly. And it’s also very useful for detecting matter that we can’t see.

But here’s the key: gravitational lensing is not described by Newton’s laws of motion.

It’s an effect of gravity, yes. But it’s an effect of gravity on light, not matter. Newton’s laws of motion don’t apply.

If gravitational lensing can help confirm dark matter, that would give astronomers a lot more confidence in its existence.

This is a galaxy cluster:

Okay, see that weird, wiggly arc of a galaxy?

That is not what the galaxy really looks like. It’s a normal disk galaxy.

This is an effect of strong gravitational forces. This galaxy is a very distant galaxy, and it appears distorted because the light reaching our instruments is distorted. That light is getting bent around a galaxy cluster in the foreground.

Lucky for us, the amount of distortion depends on the strength of the foreground cluster’s gravity. And there is way too much distortion for the observable mass in the foreground cluster to account for.

Apparently, there is invisible mass exaggerating the gravitational effect in the area and distorting that foreground galaxy’s image even more.

Namely…dark matter.

We also know that…

Dark matter doesn’t interact

We already know that dark matter doesn’t interact with light: that explains why we can’t see it, whereas we can see baryonic matter.

But it doesn’t seem to interact with anything else2, either.

Meet galaxy cluster 1E0657-56…

(I know…astronomers come up with the most imaginative of names.)

This is technically two galaxy clusters that passed through one another about 100 million years ago.

It’s not really pink and blue. This is a false-color image: that is, an image showing observations in wavelengths other than visible light. The non-visible wavelengths are color-coded so we know what type of radiation we’re looking at.

In this case, hot intergalactic gas — made of baryonic matter — is shown in pink. The actual galaxies are the bright blobs.

Notice how the pink doesn’t line up with where the galaxies are?

As the two clusters collided, so did the gas, and it was swept clear of the clusters. But the same isn’t true for the dark matter.

Gravitational lensing reveals where the invisible clumps of dark matter are. That’s the purple haze. And as you can see, it’s very much still centered on the two clusters.

The dark matter didn’t collide with anything. That is, it didn’t interact — with the baryonic matter present or with itself.

And that lack of interaction has given it a critical role in the story of the universe…

It could clump early on

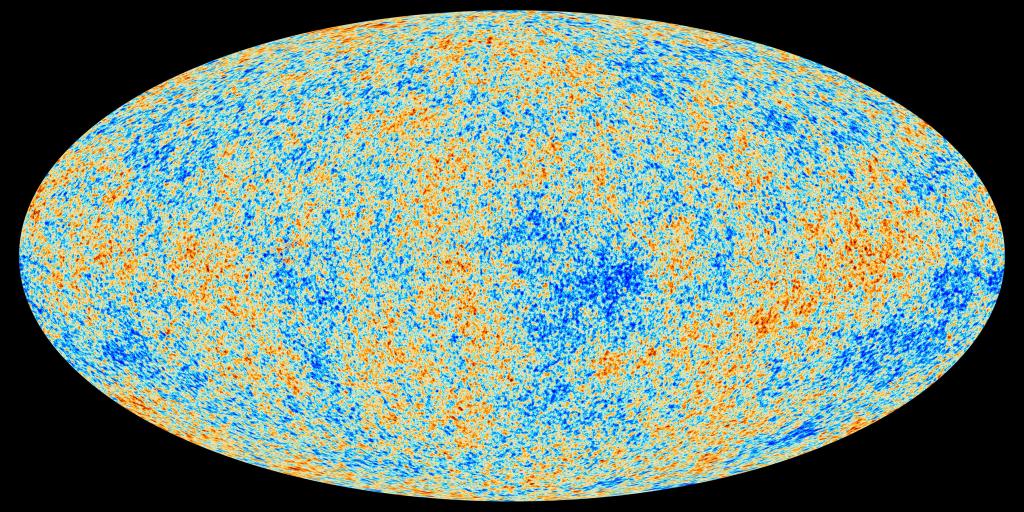

When the universe began, it was a soup of radiation and subatomic particles. And the radiation was way denser than the matter.

For 50,000 years, radiation dominated the universe.

The radiation density kept matter hot and evenly spread throughout the universe. It couldn’t clump together and start forming galaxies.

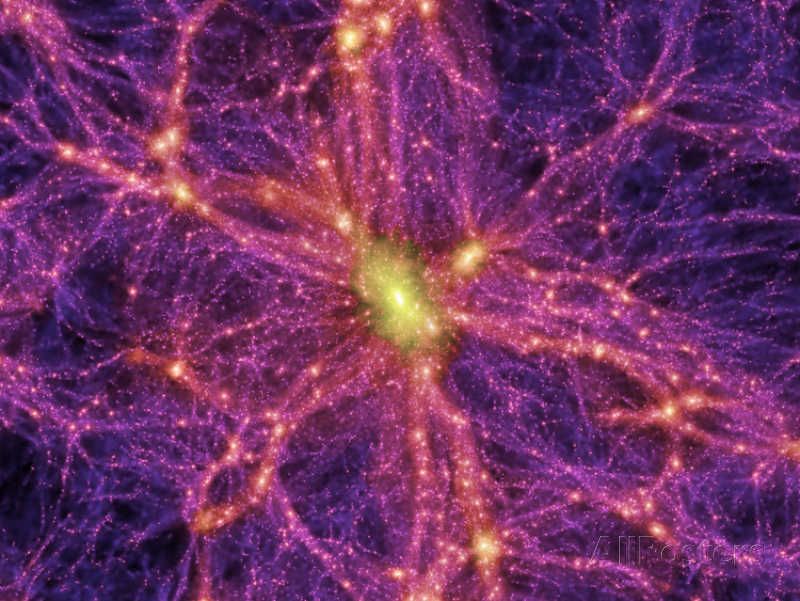

But dark matter could — because it doesn’t interact with anything. Light couldn’t touch it, and the captive matter couldn’t get in its way. It doesn’t even interact with itself, but it does have gravity…and it responds to gravity. That’s how we were able to detect it by observing galaxies’ rotation.

Dark matter drew together under its own gravitational influence to form long, spiderweb-like strands…

…and when baryonic matter finally dominated over radiation, 85,000 years after the universe’s beginning, it was drawn straight into this web like insect prey.

Cosmically speaking, that is. By human perception, this took almost a billion years.

In fact, dark matter is necessary to explain our observations of the universe. Without an invisible dark matter web, baryonic matter should not have been able to form galaxies as quickly as it did.

And there’s more…

Dark matter outweighs baryonic matter by a factor of between 5 and 10:

…and without it, the shape of space itself doesn’t make sense.

All observations point to the universe being flat: that is, space-time obeys the normal, Euclidean geometry you learn in high school, just like the “zero curvature” example below.

The shape of space is partially determined by gravity. Gravity works by curving space-time. And based solely on the gravitation from the amount of baryonic matter in the universe, space-time should flay open like a saddle (more on how we know that here).

At first glance, it’s a paradox: space-time is observed to be flat, but there isn’t enough matter for that to make sense.

Dark matter — and the mysterious dark energy, which counts because of E=mc2 — make up the difference.

There is also a possibility — as far as I know, still an open question — that dark matter is responsible for the supermassive black holes that lurk at the centers of galaxies.

It would certainly make sense: we already know that dark matter is responsible for how fast galaxies were able to form. It’s not much of a stretch to imagine that it played a key role in forming galaxies’ gravitational centers.

Dark matter is a final frontier of cosmology, second only to the elusive dark energy. It’s honestly kinda crazy just how much we’ve been able to learn, considering that we can’t directly detect it.

Next up, we’ll travel back in time to revisit the universe’s first moments…and round up what we understand of the Big Bang!

- See footnote 2: axions’ continued status as a leading candidate implies that dark matter may actually be able to interact with baryonic matter to some degree. ↩︎

- A 2018 research paper suggests that interaction between dark matter and baryonic matter may be possible. That’s quite a few years ago, but a September 2024 article in the Scientific American says that axions are still a leading candidate for dark matter, and axions are theorized to interact with baryonic matter. [Citation: Slatyer, T. R., & Tait, T. M. P. (2024, September). What if we never find dark matter? Scientific American, 331(2), 30–37.] ↩︎

Leave a reply to Simon Cancel reply