That has got to be the single strangest post title I’ve ever written.

Of all the whacky branches of science out there, cosmology almost takes the cake — second only, I think, to the downright trippy world of quantum mechanics. After all, cosmology is the study of the universe itself: its past, present, and future, its nature, and the why of it all.

“Cosmology demystified” feels like a contradiction in terms. The very definition of an oxymoron.

It is truly mind-blowing just how much evidence astronomers have gathered about the nature of our universe and its future, and even more incredible that we’ve put together a coherent story that fits the facts.

So, how about we untangle those facts and lay out our universe’s full story, plain and clear?

- Where are we now?

- What is the universe like?

- How did we get here?

- How does matter behave?

- Where are we going?

- How do we know?

Where are we now?

You could say, to quote Carl Sagan, that we live on a pale blue dot suspended within a sunbeam.

But that’s still a view from within our own solar system.

If we were to zoom out even farther — as they say in Star Trek, where no one has gone before — we would see that we are barely a speck in a universe of specks:

Dang…let’s take a closer look at that last frame.

Yup. That’s us. Just a tiny speck. And that speck represents a whole supercluster of galaxies.

You can see that, on large scales, the universe is actually quite uniform. It appears largely the same in all locations, no matter which direction we look.

That, in fact, is the cosmological principle: that the universe is both isotropic (appears the same in all directions) and homogenous (appears the same in all locations).

Or, in plain English: Any observer in any galaxy sees the same general properties for the universe.

This is powerful, and fundamental to our study of cosmology. It means that our vantage point isn’t unique. The laws of physics we observe apply everywhere.

More importantly, the universe is knowable.

We don’t have to go back to the drawing board and figure out the fundamental physics again for every galaxy we study.

What is the universe like?

We live in a flat, expanding universe.

Okay, before the flat earthers have a field day: I don’t mean to say that the universe is flat like a pancake. I mean to say that the fabric of space has no curvature. That is, if you try to travel in a straight line over a large distance, your path will work out exactly as you expect: you’ll travel in a straight line.

In a universe where space-time were curved, you could try to travel in a straight line, but it wouldn’t work. Your path would end up curved.

Our universe obeys the same geometry you learn in high school, which is very convenient for us humans!

The universe is also expanding. By that, I mean that the fabric of space itself is sort of “stretching,” carrying galaxies apart from one another:

And that’s not all. That expansion is accelerating.

In other words, the rate at which space is stretching apart is speeding up. (More on that shortly!)

How did we get here?

As far as we know — and cosmology is a rapidly advancing field, so this has definitely come into question — everything started with the Big Bang.

There is a common misconception that this was a localized explosion.

Rather, at the beginning of time (as we know it), the universe was presumably an infinitely dense point — essentially, a singularity (like a black hole).

Then, suddenly, it began to stretch apart.

The Big Bang occurred everywhere, across the whole universe. It refers to that first moment of time.

At the very instant of the Big Bang, the four fundamental forces of nature — gravity, the electromagnetic force, the strong force, and the weak force — were unified. That is, they behaved as one.

But this only works under the extremely high-energy conditions of the beginning of time.

After just 10-36 seconds, the strong force and the electroweak force — a combo of the electromagnetic force and the weak force — disconnected.

This released an absolute crap ton of energy, triggering 10-32 seconds of inflation.

It is likely that the perfect flatness of space is at least partially an illusion: it appears completely flat for the same reason that fools flat earthers…

Viewed from close-up — that is, from the ground — Earth’s surface sure looks flat.

But that’s only because we’re super tiny compared to the Earth, and we just see a tiny segment of the curvature at a time. Take a look at how, if we zoom in on a section of a circle, the edge appears flat:

Anyway.

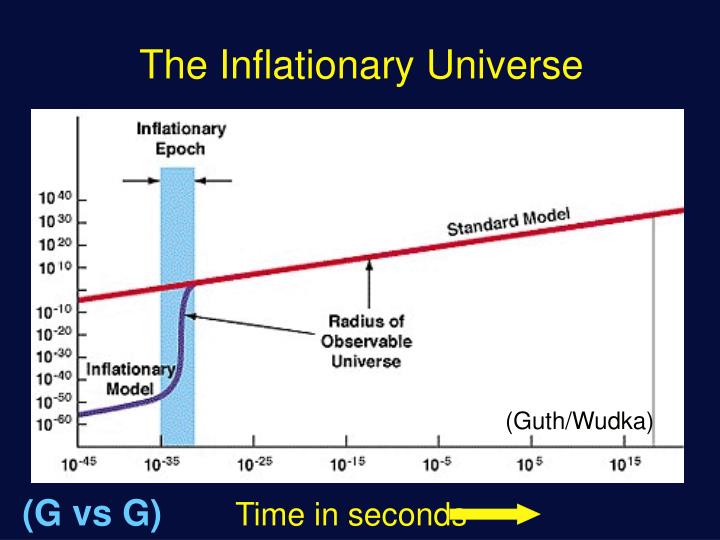

During inflation, the universe expanded by a factor of 1050…

This sudden expansion would have forced space-time to flatten, making the universe appear even flatter than it is. Likely, space-time truly is almost completely flat.

Fast-forward to 10-6 seconds…

Okay, that is admittedly not a very large time jump. It’s still been only a fraction of a second since the beginning of time.

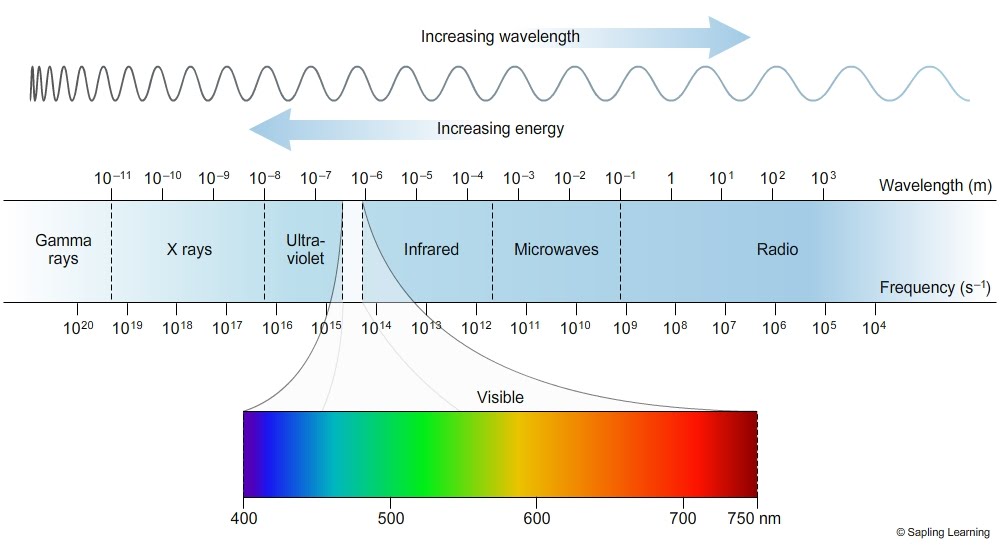

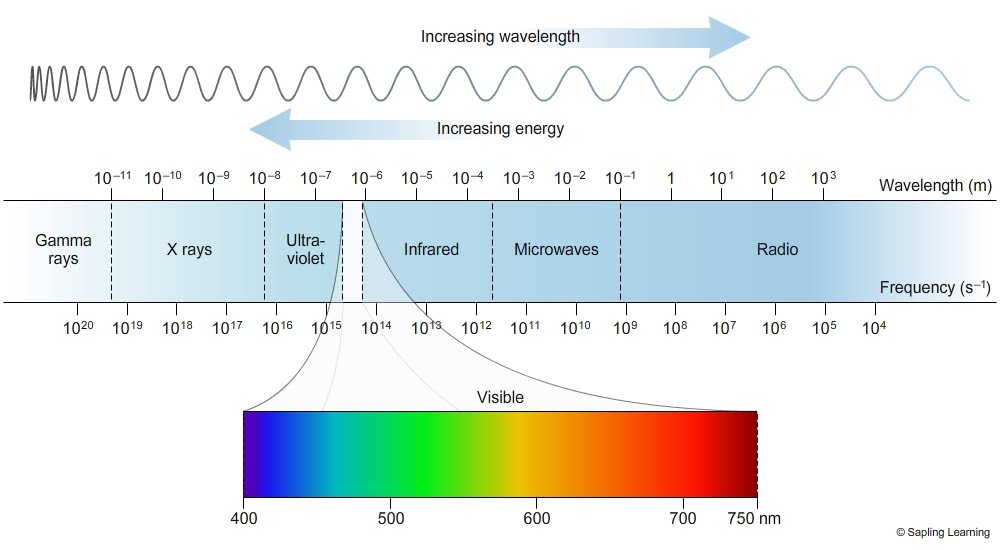

At this point, the universe was filled with high-energy photons with temperatures of 20 trillion K (kelvins). We’re talking gamma rays:

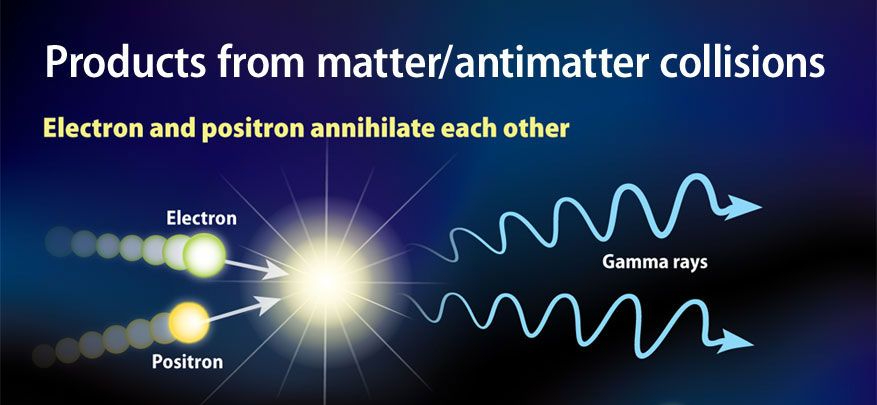

Such high-energy photons easily convert to matter-antimatter particle pairs. But the universe’s scale was still fairly small, and all its matter and energy was packed closely together. Particle pairs wouldn’t last long before colliding, annihilating one another, and converting their mass back to gamma rays.

So, the early universe was a soup of energy, flickering between matter-antimatter particle pairs and photons and back again.

But as the universe continued to expand, its matter and energy was able to spread out a bit, and its temperature fell — until it was no longer able to convert photons into particle pairs.

After 1 minute, the existing matter-antimatter pairs would have combined and converted to photons for good.

In fact, there shouldn’t be any matter left in the universe. But for some reason we haven’t figured out, the Big Bang produced just slightly more matter than antimatter. One in a billion particles of matter survived with no antiparticle to annihilate it.

2 minutes after the Big Bang, the universe cooled enough for subatomic particles to begin combining to form the first deuterium nuclei…

…and at 3 minutes on the clock, deuterium nuclei combined to form the first helium nuclei.

Still, the universe continued to expand and cool. Nuclear reactions slowed down after 4 minutes, and after 30 minutes, they stopped completely, bringing the first era of nucleosynthesis to an end.

Models predict that the universe contained 75% hydrogen nuclei, 25% helium nuclei, and trace amounts of the isotope lithium-7.

At this point, the universe held a temperature of 1 billion K…and still continued to expand.

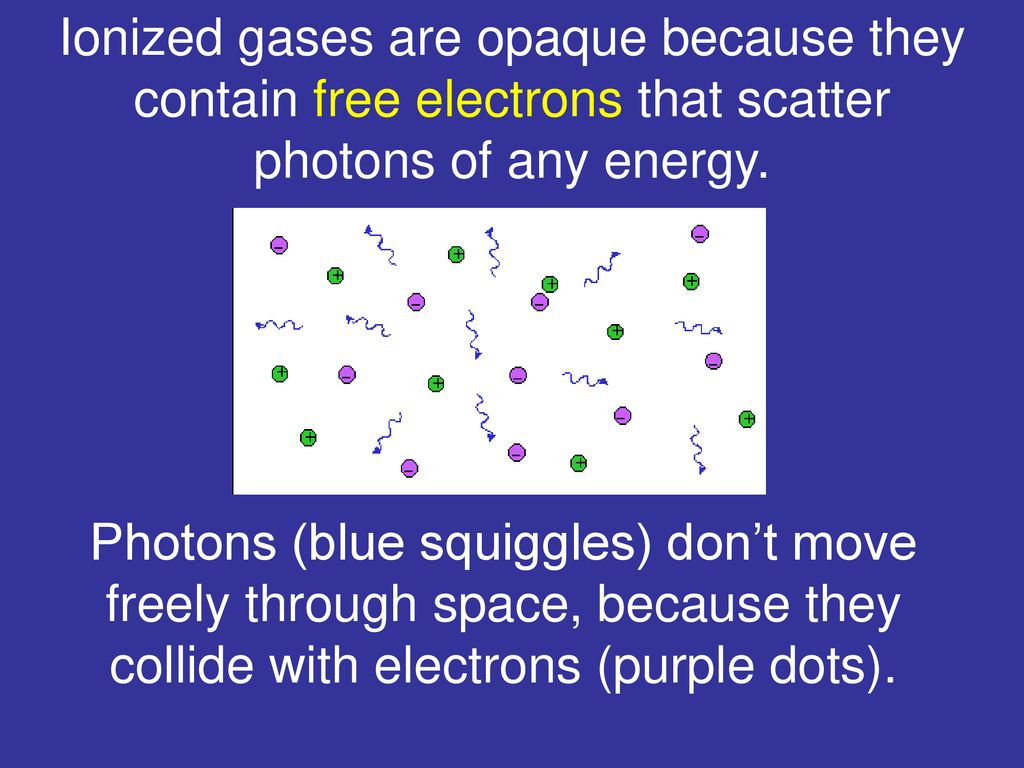

Now, the density of radiation was still greater than the density of matter. And atomic nuclei had not yet combined with electrons for the first time, so electrons floated free and never got far before rebounding off a photon and exchanging energy.

The result? Their cooling was linked, and radiation kept matter spread out, preventing it from clumping under the force of its own gravity.

For 50,000 years, radiation dominated the universe.

But dark matter was different.

As far as we know, it doesn’t interact with radiation (hence the “dark” moniker), ordinary matter, or even itself. It only interacts gravitationally, by distorting space-time.

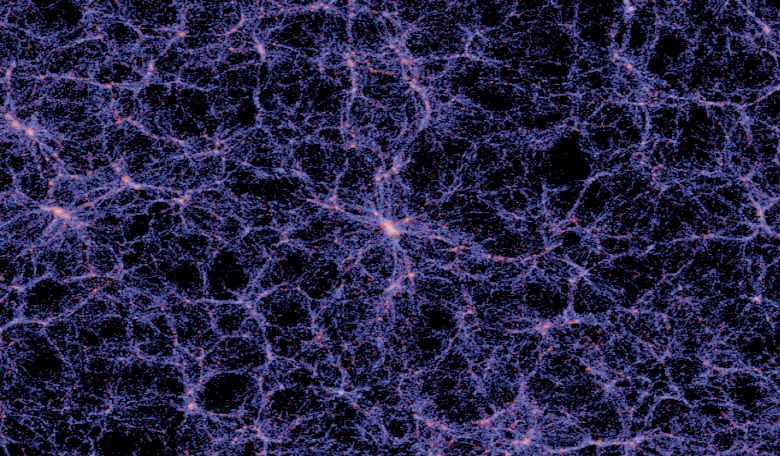

It was able to get a head start on clumping, and it drew together into long stands, like a great cosmic spiderweb…

…and, when the universe expanded enough for radiation to thin out 50,000 years later, ordinary matter was drawn slowly in like insect prey.

Matter began to clump together to form the clouds of gas that would one day become galaxies. But electrons still had yet to combine with atomic nuclei to form atoms. Photons still scattered off the free electrons and couldn’t move freely through space.

If life could have existed back then, you can imagine floating in a spacesuit, looking around you. But all the light rays — the photons — that enter your eyes have come from a very short distance away, only recently scattered off a nearby electron. You can’t see very far at all. It’s like being shrouded in fog.

In other words, the universe was opaque.

Finally, after 85,000 years, expanding space carried the gas apart…until the free electrons were too far apart to interact with photons.

At this point, as you float in space, light begins to enter your eyes from more distant locations. It’s able to travel across the universe uninterrupted, reflected off more distant matter. You can see farther.

The universe began to become transparent.

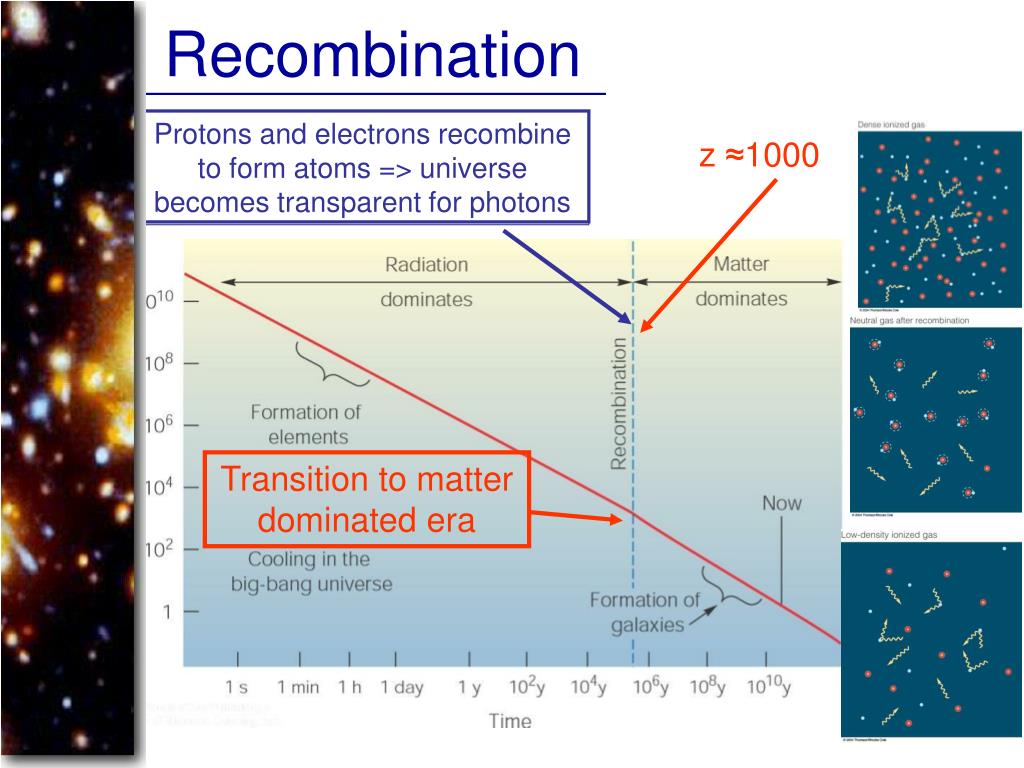

As the universe continued to expand, it cooled to only 3000 K, comparable to the coolest stars. Atomic nuclei were able to capture and hold free electrons.

The first atoms — neutral hydrogen — began to form. This moment is, misleadingly, called recombination.

It would be more accurately called simply “combination” — no “re” prefix — because protons and electrons had never combined before.

With the gas no longer ionized, the universe became completely transparent.

It became transparent because there was no longer constant interaction and energy exchange between photons and electrons. But that also meant the cooling of radiation and matter was no longer linked.

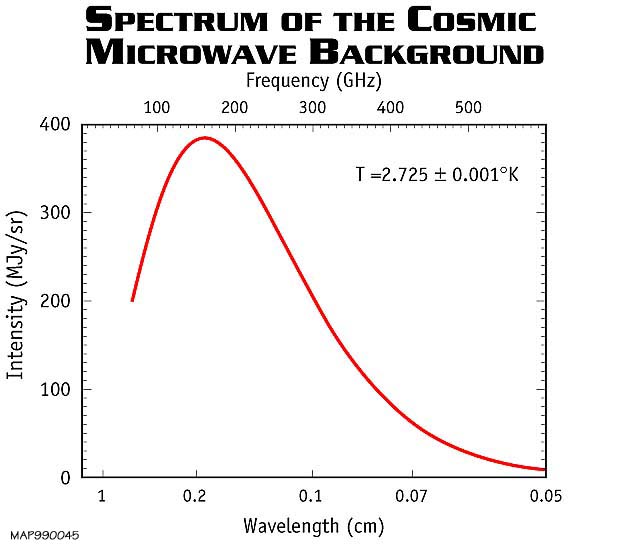

While the matter in the universe continued to cool, the photons of the time retained the temperature of the gas at recombination: 3000 K. Those photons began the long journey to Earth, and are visible today as the cosmic microwave background radiation, or CMB.

Remember that before recombination, the universe was opaque or at least partially opaque. Any light from before this time is very unlikely to reach Earth, because it can’t travel very far before rebounding off a free electron.

Therefore, the CMB is like a blackout curtain. It’s the farthest we can peer back through time.

Meanwhile, the gas in the universe continued to cool, all the way into infrared wavelengths…

For 400 million years. the universe expanded in darkness. This is often referred to as the “dark age.”

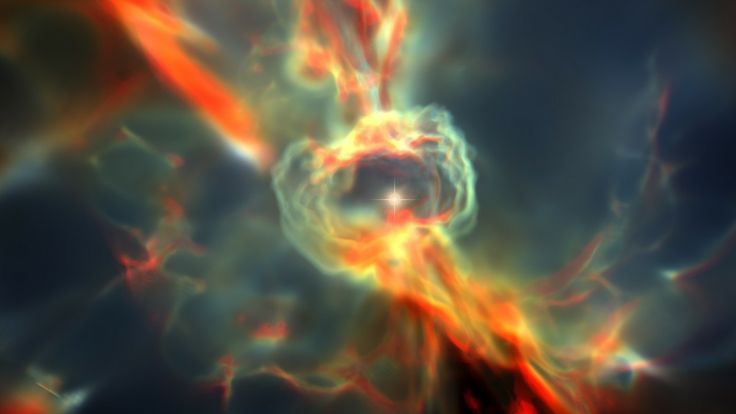

Then, finally, the first stars began to form.

The universe would have contained only the material produced in the first nucleosynthesis — hydrogen, helium, and only trace amounts of lithium-7. These were the “ingredients” available to form the first stars.

This is the moment known as “first light” or “cosmic dawn.”

Such stars would have contained almost no “metals” — astronomy jargon for elements heavier than helium. Models predict these stars would have been massive, bright, and lead very short, explosive lives.

Light dawned on a universe in chaos.

This first violent burst of star formation emitted floods of ultraviolet light and re-ionized the diffuse gas throughout the universe. Astronomers call this moment re-ionization. It marks the start of a new age: the age of stars and galaxies.

At a few hundred million years on the clock, the young universe was beginning to fill up with galaxies — and the abundant dark matter that tends to accompany them, outweighing ordinary (baryonic) matter by up to a factor of ten.

And though the universe had expanded considerably by then, its scale was still fairly small. Galaxies were quite near one another.

That means a ton of mutual gravitation.

That gravitation slowed the expansion. The graphic below credits dark matter, and indeed, its gravity definitely did most of the heavy lifting!

The expansion slowed, but it didn’t stop. So, eventually, expanding space carried galaxies too far apart for their mutual gravitational attraction to do much.

That’s when dark energy took over.

Just under 5 billion years ago, the slowing reversed — and the expansion sped up. Today, we live in a universe whose expansion is still accelerating.

That is, the rate at which galaxies recede from another, carried apart by the expanding space-time between them, is increasing.

How does matter behave?

In the grand scheme of the cosmos, galaxies are common units of structure, just like planets in solar systems or stars in star clusters. But there are structures even more massive: galaxy clusters, superclusters, and filaments.

Galaxies, galaxy clusters, and superclusters make a lot of sense. Matter gravitates together into a round shape, often flattened to a disk (due to conservation of angular momentum) like a spiral galaxy.

But, at first glance, filaments don’t make sense.

Filaments are long and string-like, making up a vast cosmic spiderweb. Gravity doesn’t usually produce that kind of shape.

The simple answer comes in the form of dark matter. Remember that it was able to clump early on. Dark matter formed these long, spiderweb-y filaments, and baryonic matter was later drawn in like insect prey.

That still doesn’t explain how dark matter formed filaments, though.

Astronomers suspect the answer lies at the quantum level. According to the whacky world of quantum mechanics, the universe could never have been completely, perfectly smooth, cosmological principle or not. Tiny quantum fluctuations would have existed.

I’m talking about fluctuations and imperfections smaller than even the smallest subatomic particles.

Here’s a simple representation of how quantum imperfections can make the universe behave just a little differently than we expect:

Mechanically, these fluctuations would have been like bubbles of energy, forming and vanishing continuously. They would’ve started out small, but as the universe expanded, they would’ve been stretched out and magnified.

These fluctuations would be subtle. Large in size, small in the actual effect they have on the universe. But they could have resulted in subtle variations in gravitational fields.

That is how we get filaments and the great voids in between — and the massive superclusters, galaxy clusters, and galaxies we see today.

Where are we going?

Dark energy is a critical piece of this puzzle. But as we explore this question, we’ll first look at the universe as cosmologists did before they had the first clue about it.

Then we’ll add dark energy back in, and see how everything falls into place.

Cosmologists used to say that “geometry is destiny.” That is, the shape of space — positively curved, negatively curved, or flat — determined the future of the universe.

Why?

This comes down to the principle that gravity is a result of curved space-time. Put simply, matter causes space to deform, and the curvature of space tells matter how to move (in, say, an orbit).

In the simplest terms, you can imagine setting a heavy object on a trampoline. The trampoline dips down beneath the object’s weight. A less massive object will then roll downhill toward the massive object.

That is essentially what happens between the Earth and the moon, the sun and the Earth, and our galaxy’s gravitational center and every star in orbit. The smaller object is compelled to orbit because of the way space-time is distorted.

Now, imagine if there were a ton of mass in the universe (high-density scenario). One object’s “dimple” in space-time has barely flattened out before the next one begins. The universe will begin to curve in on itself, due to the combined force of gravity from all its mass.

See what happens as we start out with a completely empty universe, and then add more mass, bit by bit:

We end up with a closed universe.

Such a universe cannot expand forever. Remember that the expansion of the universe is due to the expansion of space-time itself. If space-time is contracting around lots of mass, then the expansion is going to slow and stop.

On the other hand, imagine if there were barely any matter at all (low-density scenario). In fact, in this scenario, there is too little gravitation to keep the universe flat, much less curved in on itself; it’ll splay open like a saddle.

In such a universe, gravitation between masses is far too weak to counteract the expansion, and the universe must expand forever.

What about a flat universe? To hold space-time perfectly flat, it must have just enough matter — have exactly the right density — to bend space-time ever so perfectly, holding it at just the right balance between splayed and curved in.

Such a universe still does not have enough gravitation to slow the expansion, and it will expand forever.

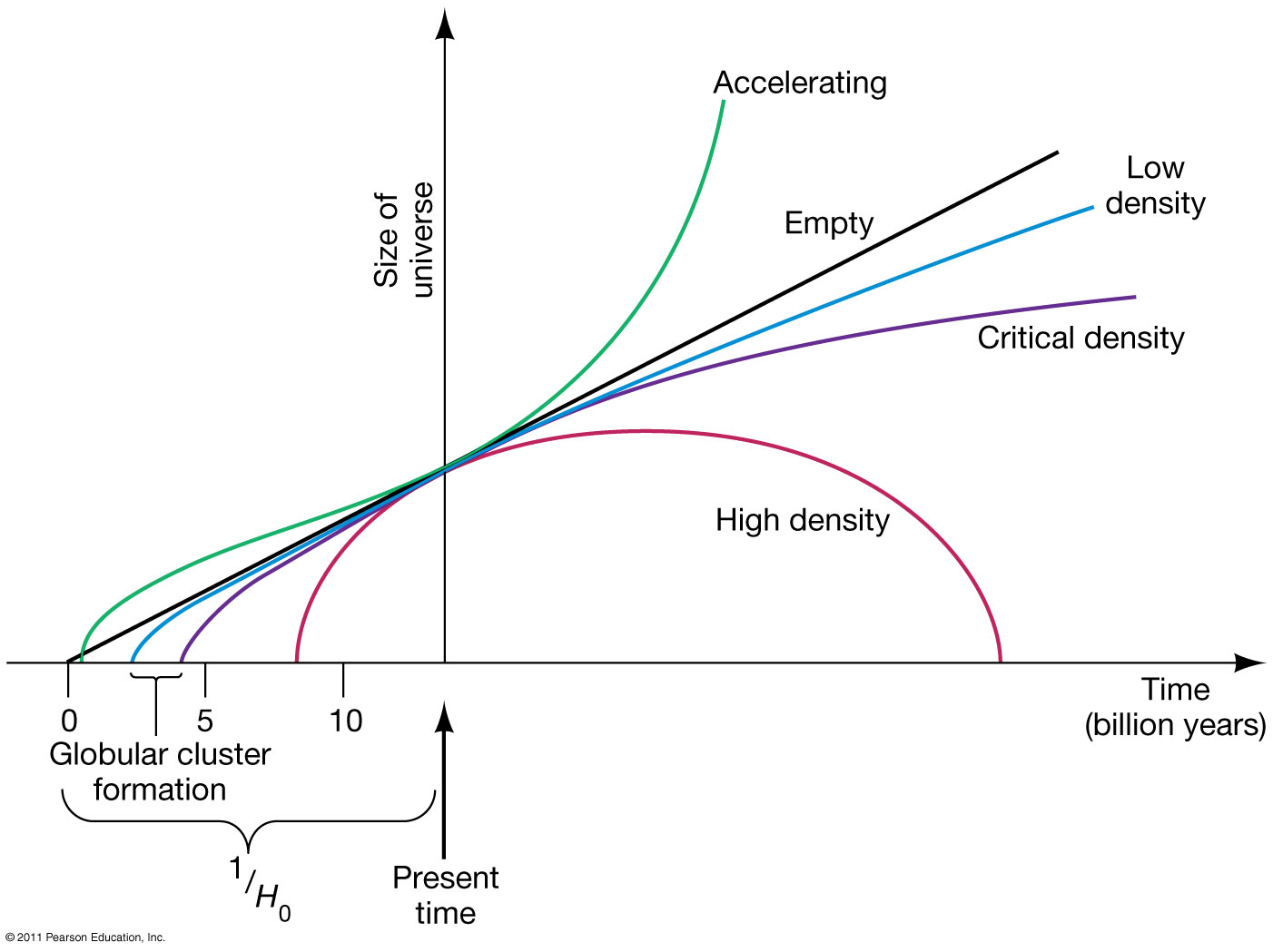

You see these scenarios in the graph below: the size of a high-density universe eventually rebounds and decreases, but the size of a critical density, low-density, or completely empty universe increases forever (at somewhat different rates).

So which is ours?

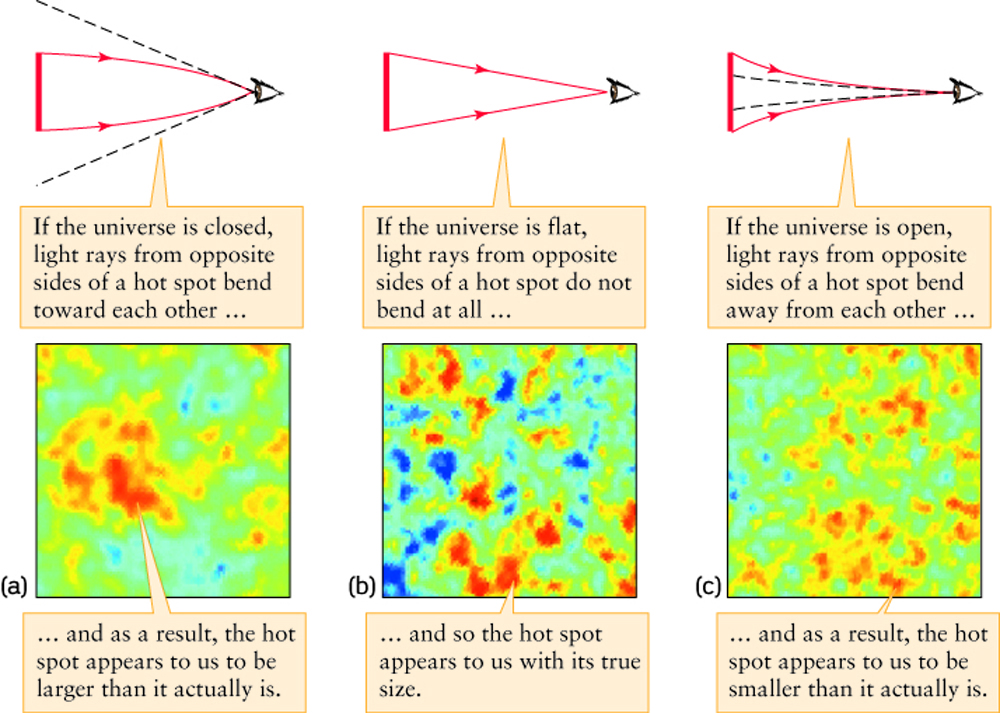

It is actually possible to measure the curvature of space-time. We know what distant observations would look like in a positively curved, negatively curved, or flat universe:

We observe our universe to be flat. And this is, frankly, incredible.

It means our universe has exactly the right density — called the critical density. And that’s not an optimal value that sort of “clicks” into place. It’s a balancing act. We have a perfectly balanced teeter-totter.

Inflation helps somewhat. We know that our universe’s perfect flatness is likely an illusion. But that doesn’t change the fact that our universe is still really dang close to being perfectly flat.

And here lies cosmology’s conundrum.

One, our universe must have critical density (or close), but…it just doesn’t seem to.

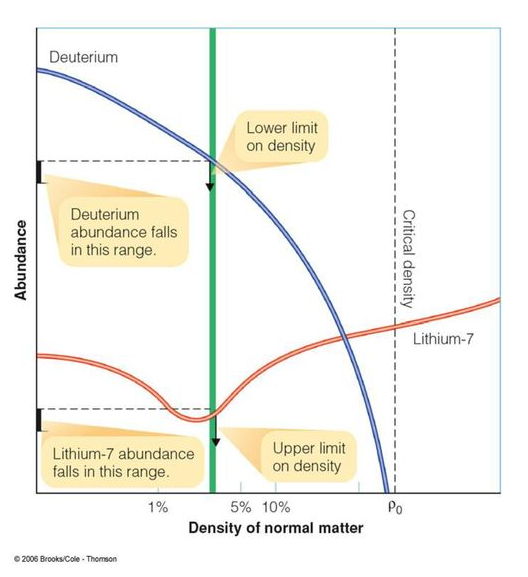

Using known properties of deuterium and lithium-7, the lightest and heaviest nuclei (respectively) to be synthesized in the first nucleosynthesis, we can put some conveniently narrow constraints on the actual measured density of the universe…

…and it just doesn’t add up. Baryonic matter can’t possibly make up the entire critical density. Even dark matter can’t make up the difference.

The other problem is with the universe’s age. Take a look at the graph below…

See the purple line? Setting aside for a moment the problem of actually reaching the critical density, that shows the changing size of the universe over time if space-time is flat.

The purple line reaches zero size — that is, the moment of the Big Bang — up to several billion years after the oldest objects in the universe are calculated to have formed.

Of course, it would be unscientific not to consider that those objects’ calculated ages are wrong. But that wouldn’t solve the discrepancy between measuring flat space-time and yet measuring a density far below critical.

Dark energy solves all these problems in one fell swoop.

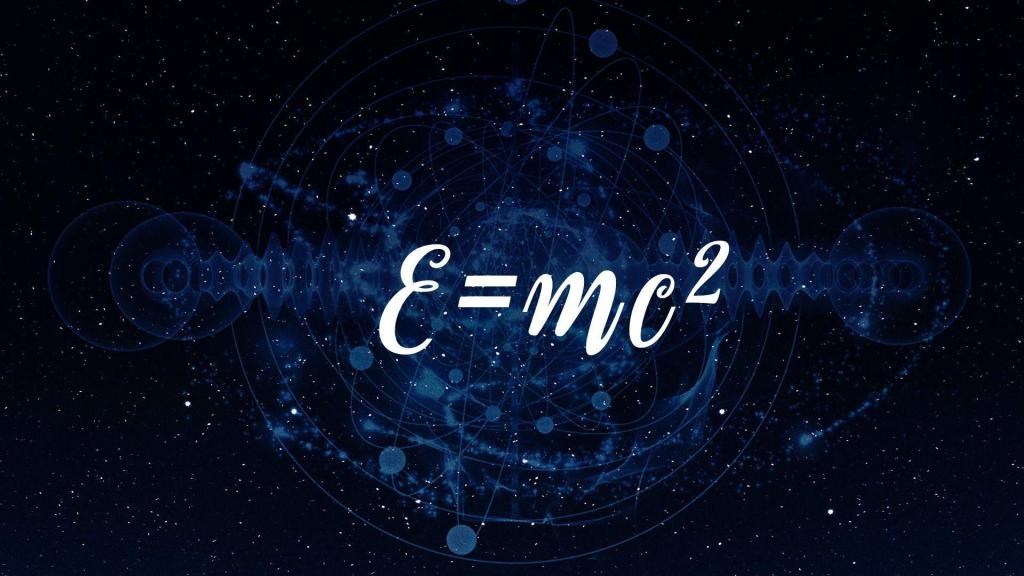

First, it solves the critical density problem. According to Einstein’s famous equation, E=mc2, matter and energy are equivalent…

Which means that, when it comes to determining the density of the universe, energy counts as matter.

Any energy, in fact. Including dark energy.

Combined, dark energy, dark matter, and the matter and energy that you and I are familiar with (like the energy from the sun, or the light from your desk lamp) make up the total density of the universe.

Second, dark energy is the mysterious anti-gravity force driving the current acceleration. And our accelerating expansion means that the early universe was expanding slower than it is today.

In other words, the universe would’ve taken longer to get to its current scale.

The universe can be older — older than all the objects within it. Paradox solved!

Finally, it makes sense for the universe to be flat.

But what does dark energy mean for our future?

It actually makes the question, “Where are we going?” difficult to answer. If the universe were under the command of gravity alone, our future would depend on the curvature of space-time.

Dark energy, though, counteracts gravity. It takes the universe’s future out of gravity’s hands entirely.

Dark energy means that it doesn’t matter whether space-time is positively curved, negatively curved, or flat — even a “closed” universe need not rebound and collapse. In any scenario, expansion can continue forever.

Billions of years down the line, our future will depend on the specific nature of dark energy — something we’ve barely even begun to figure out.

At least we’ve got plenty of time!

But I know what you’re gonna ask me…

How do we know?

Never hesitate to ask this question. It’s the most important question you can ever ask in science.

It is utterly mind-blowing to me that, given the absolute mind-boggling nature of cosmology, this is a question I can answer in full. So, let’s lay out the evidence…and as you’ll see, there’s quite a bit!

Look-back time

There is a fundamental property of light: it travels at a set speed (in a vacuum) of about 300,000 kilometers per second.

It does not travel instantaneously. It takes time to travel.

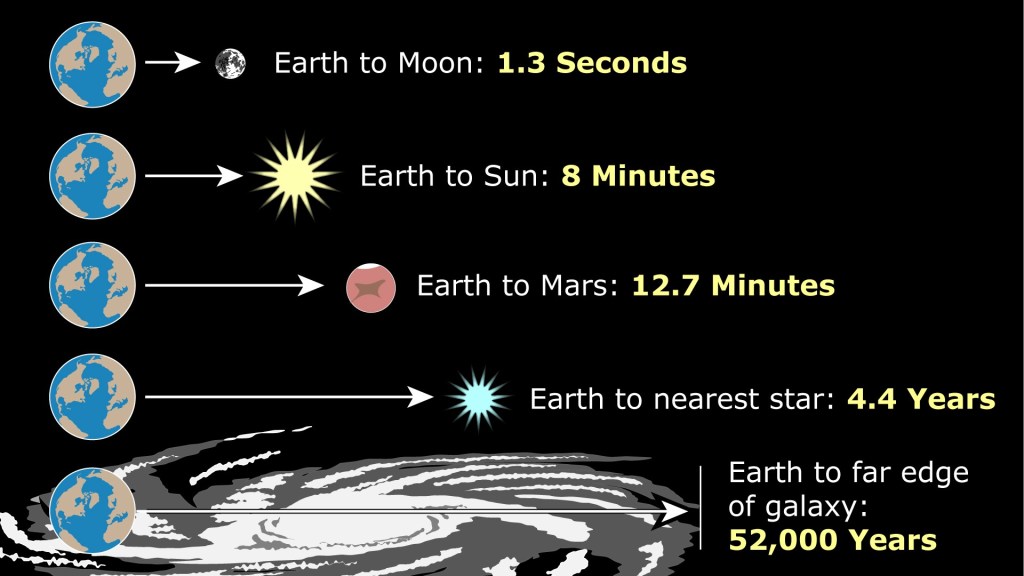

When studying objects in our immediate cosmic “neighborhood,” astronomers must contend with the fact that we never see objects — even ones as close as the moon — as they appear right now. We see them as they appeared when the light currently entering our eyes left them.

When studying the universe’s history, this mechanic of light becomes very useful.

If you look at an object 13.8 billion light-years away, you are seeing that object as it appeared when the light entering your eyes left it — 13.8 billion years ago.

You’re looking back in time.

That is fundamental to our study of the universe. It makes cosmology possible. Peering through light-travel “eras” is like digging through geological strata in rock: the deeper you go, the older the fossils. Cosmology is paleontology of the universe.

Now you see why I said that the cosmic microwave background radiation is the “farthest we can peer back through time?” 😉

But there’s a catch…

Cosmological redshift

The light doesn’t reach us in the same condition that it left.

In fact, past a certain distance, everything we see in the universe is redshifted: that is, its light looks “redder” than it was when it was first emitted.

This is bedrock evidence that the universe is expanding.

When space-time stretches like a rubber sheet, light stretches right along with it — into longer wavelengths.

Longer wavelengths appear redder.

Which brings me to…

The Hubble Law

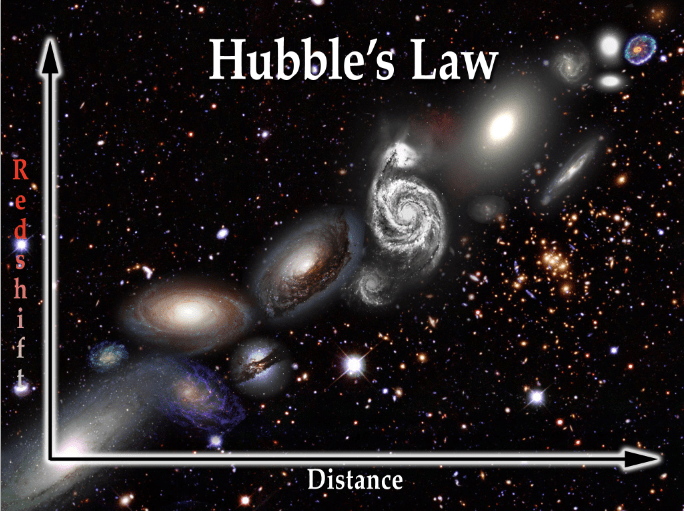

With the help of data from Vesto Slipher, Edwin Hubble observed that a galaxy’s redshift is proportional to its distance. This is known as the Hubble Law (though some have questioned whether we should call it the “Hubble-Slipher Law”; credit where credit’s due, after all).

This only makes sense if the space between galaxies is expanding. Galaxies that are more distant from Earth have more space between them and Earth. More space expanding between us and them means they are carried away from us faster, and their measured redshift is stronger.

Note that any other planet anywhere in the universe would observe the same effect. The Hubble Law does not indicate that Earth is at the center of the universe (and, as we know, there can be no center of an infinite universe; geometry doesn’t work like that).

The redshifts of galaxies also clue us in to the accelerating expansion of the universe. Depending on the distances of the objects we study — equivalent, due to light travel time, to their age — we measure different values for the rate of expansion. More distant objects give us a smaller value. Nearer objects give us a larger value.

Now, for one of the most important pieces of evidence — essentially, cosmology’s smoking gun.

The CMB

Remember the cosmic microwave background radiation we mentioned earlier — the radiation signature left over from recombination?

The CMB was predicted decades in advance. We even got the details right. Physicists had predicted that, due to cosmological redshift, its 3000 K photons would be redshifted to only about 2-3 K by the time they reached Earth.

They had also predicted that it would have a near-perfect blackbody radiation curve. For this post, you don’t need to know what the heck that means — just that we predicted it would look like this…

…and, it turned out, it did!

The temperature was dead-on, too, with a very small error margin. Our accurate predictions give us confidence in the assumptions and understanding that led to those predictions.

But there’s more…

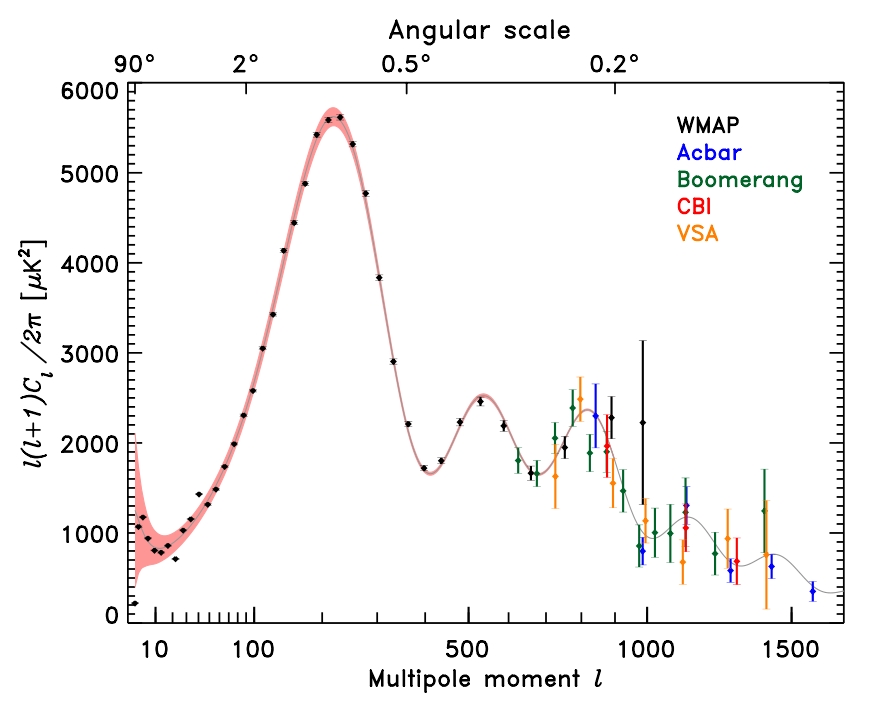

Just like how we can mathematically determine how many galaxies will appear in the night sky at different distances depending on the curvature of space-time, so too can we determine what the CMB would look like depending on that curvature.

The size and distribution of the variations in temperature of the CMB confirm a flat universe…

…which indirectly confirms the conditions needed for the universe to be flat: inflation, which would have forced the curvature to flatten, and the existence of dark matter and dark energy, which bring the universe’s density to (nearly) critical.

Also, a graph plotting the different sizes of those variations confirms even more…

The universe is flat, accelerating, and will expand forever.

The age of the universe is 13.8 billion years.

The universe contains 4.5% baryonic matter and electromagnetic radiation, 22.7% dark matter, and 72.8% dark energy.

Dark energy does exist, and in fact must exist, so that the universe’s density equals (or approaches) the critical density and it makes a speck of sense for all our data to point to a flat universe.

Those conclusions are all in the math, math that’s too advanced for me at this point in my schooling. But if you’re not convinced — and I don’t blame you! — there’s even more…

Stellar compositions

Remember how we said that the first era of nucleosynthesis produced 75% hydrogen, 25% helium, and trace amounts of lithium-7?

After those first 30 minutes of time, the next nucleosynthesis would occur in the cores of stars.

So, the first stars had to form from the mixture of material left over from the first nucleosynthesis. Now, stars’ cores are literal engines of nucleosynthesis, so they won’t reflect original factory conditions, so to speak. But their atmospheres don’t change composition.

Spectroscopic analysis of the atmospheres of the earliest stars will reveal the elemental mixture they formed from. And — conveniently — the set speed of light means that if we collect data from really distant stars, that means we’re collecting data from those earliest stars.

Remember how I said how convenient that mechanic of light is for cosmology?

Anyhow — that spectroscopic analysis reveals exactly the relative abundances that our models predict for the early universe.

Which, by extension, gives astronomers confidence in the assumptions those models are based on, and any other conclusions those same models help us draw.

It gives us confidence in our entire theory surrounding the Big Bang and the universe’s earliest moments, including the mechanics of that earliest nucleosynthesis.

Aaaand last but most certainly not least…

Type 1a supernovae

The theoretical evidence for dark energy is strong. That is, it fits neatly as a necessary explanation for both acceleration (observed from redshifts) and flat space-time.

But dark energy is a whacky idea, and like any good scientist, astronomers were reluctant to embrace it at first. They needed more evidence.

That evidence came in the form of data from distant type 1a supernovae.

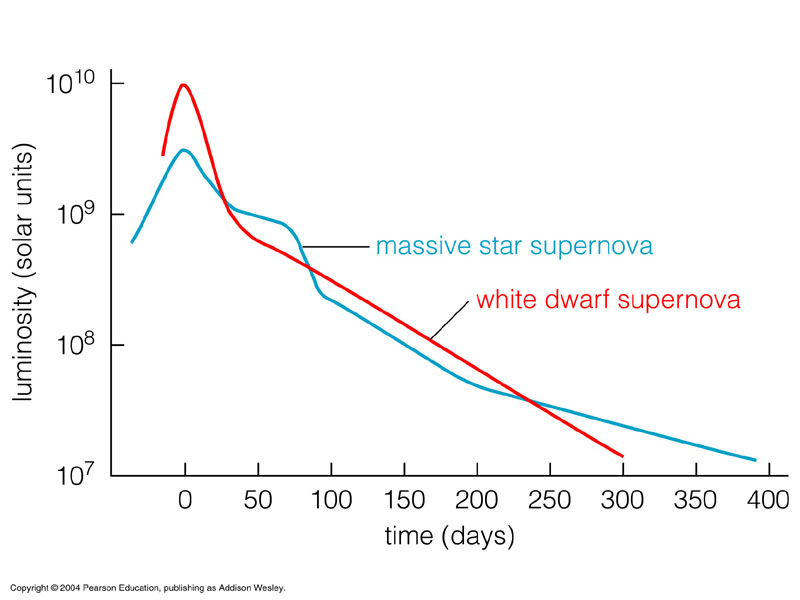

This is a type of supernova that occurs when a white dwarf‘s mass exceeds the Chandrasekhar limit of 1.4 M⨀ (solar masses).

Because this supernova explosion always occurs under the same conditions, it always reaches the same peak brightness. And, in fact, we can differentiate it from the supernova of a massive star using its light curve (the graph of its brightness over time)…

That makes it very useful as a distance indicator.

See, when you look up at a bright star in the sky, you don’t know if it’s truly quite bright, or if it just appears bright because it’s quite close to us:

But for a type 1a supernova, the peak intrinsic brightness is always the same. So, if we observe them in a different galaxy, we know how bright they are intrinsically.

They will, naturally, appear considerably fainter due to their distance — that’s their apparent brightness.

There’s a formula for relating intrinsic brightness, apparent brightness, and distance. So, it’s a simple matter to calculate the distance to the supernova. And if the supernova is in a galaxy, naturally its host galaxy is at that same distance.

Then, we measure the galaxy’s redshift and calculate its distance using the Hubble Law. We compare the two values.

We find that supernovae in distant galaxies are fainter than expected.

That is, those galaxies are farther away than the Hubble Law says they should be.

Remember that the Hubble Law arises from cosmological redshift and is bedrock evidence for the expansion of the universe. If these galaxies are more distant than the Hubble Law predicts, then the space between us and them has expanded faster than expected, carrying them apart from us more quickly than expected.

In other words…the expansion of the universe is, in fact, speeding up.

But how is that possible, if gravitation between galaxies should bend space-time and slow the expansion?

There must be some kind of force of repulsion that can counteract gravity.

This acceleration of the expansion, evidenced by supernovae brightness, is our bedrock evidence for dark energy. And, of course, dark energy is theoretically necessary to explain other observations, as we’ve covered.

That is how we know.

But there is still so much we don’t know. We have no idea what the heck dark energy is — or dark matter, for that “matter” (ha!). More than 95% of the universe remains a mystery. That’s the fun part, with cosmology — there’s always more to explore!

And there you have it, peeps — after an entire year, we are finally through our cosmology unit!

Next up, we’ll be on to something much closer to home: the formation and evolution of our own solar system, and an exploration of the planets.

Leave a reply to Jim R Cancel reply