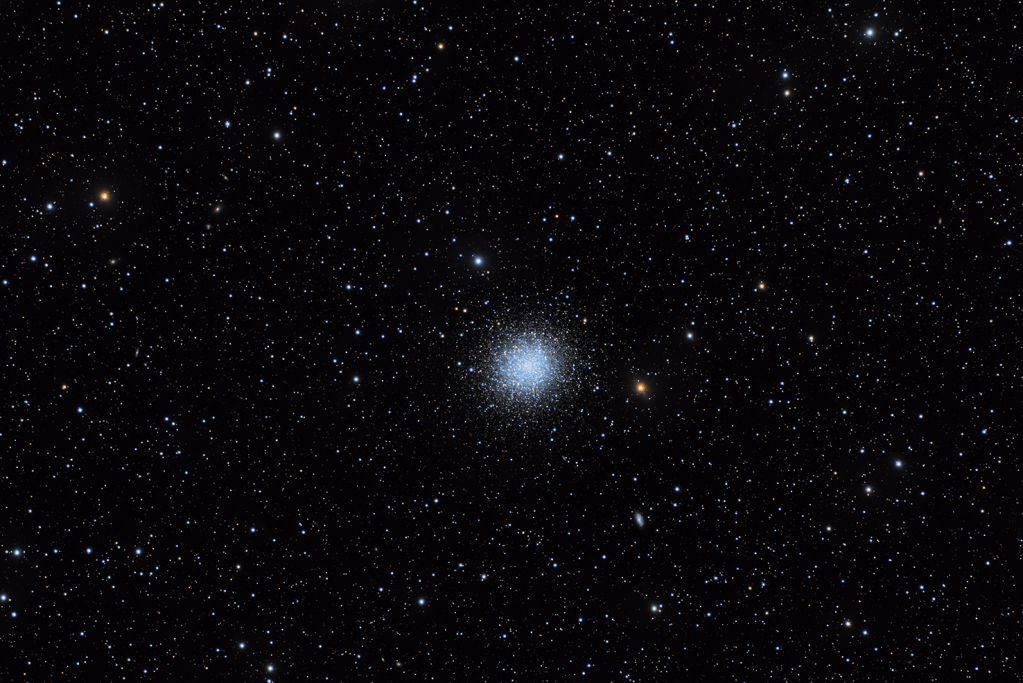

Meet Messier 13: my sentimental favorite globular cluster.

For more than a decade now, one of my favorite things has been to set up my telescopes at astronomy outreach events and show people the night sky. I have two telescopes to set up, and I take full advantage of that: one of my favorite routines is to set up Messier 13 in one, and the Andromeda galaxy in the other.

But why?

I once asked my dad, with the confidence a young girl has in her parents’ infinite knowledge, what a “globular cluster” was. And though he was a treasure trove of astronomical facts to me back then, he could give me no clear answer…

…because the answer wasn’t known.

He did, however, tell me of a leading hypothesis: that globular clusters were, in fact, the nuclei of galaxies just like Andromeda.

But we didn’t know. And there hasn’t been enough research to write about it…until now.

First things first…let’s get ourselves oriented!

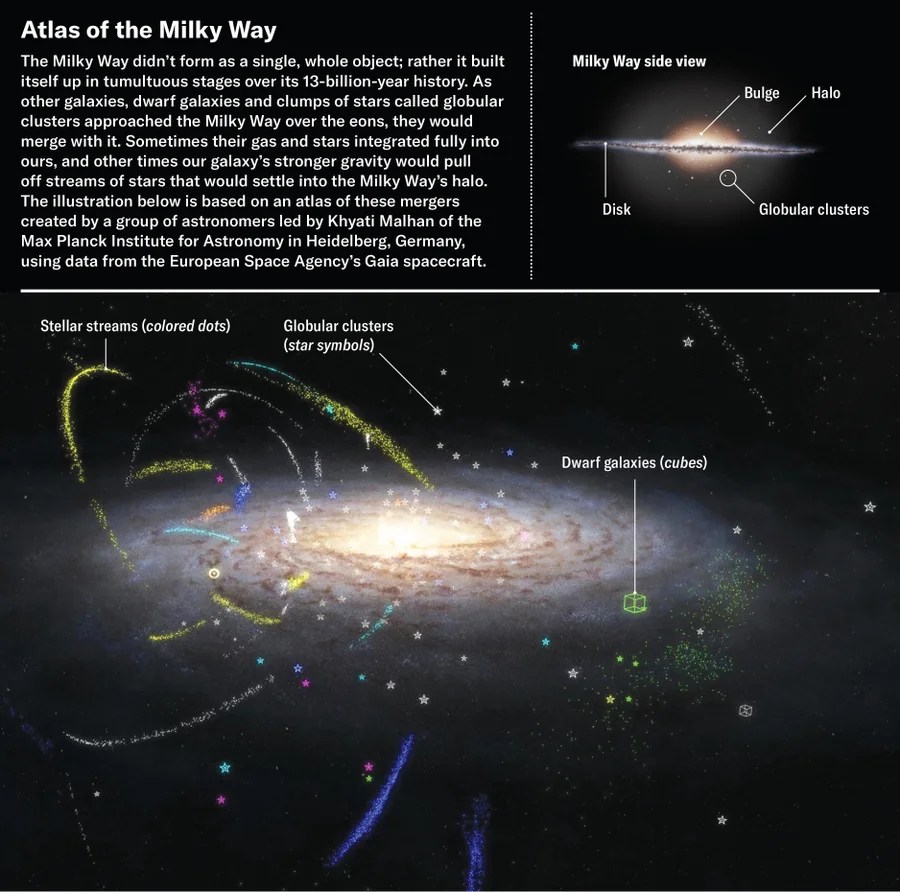

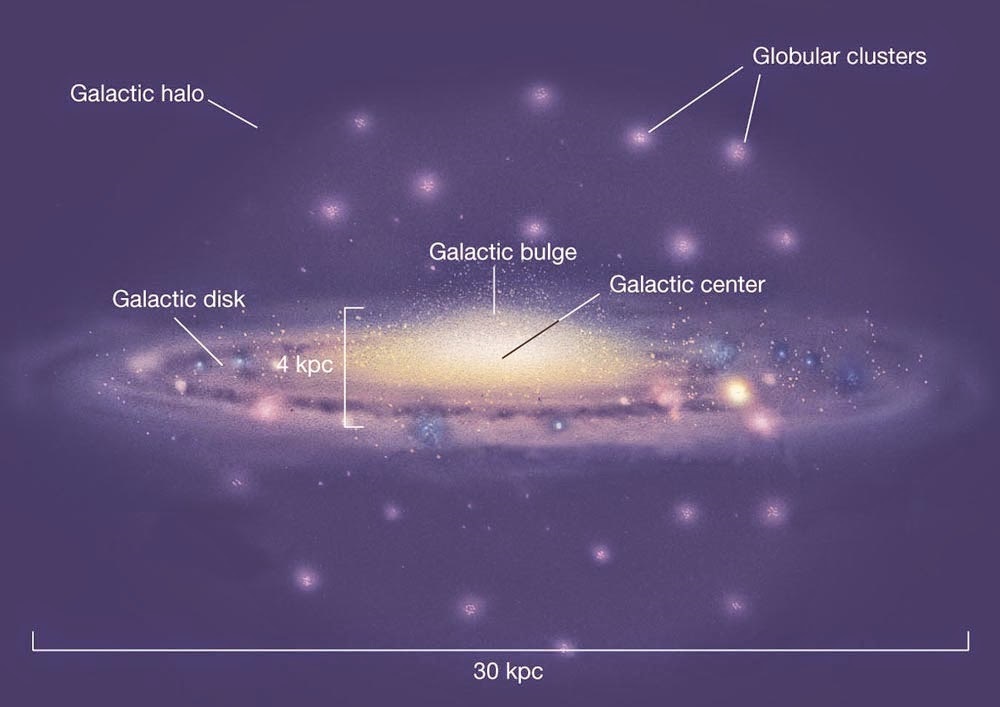

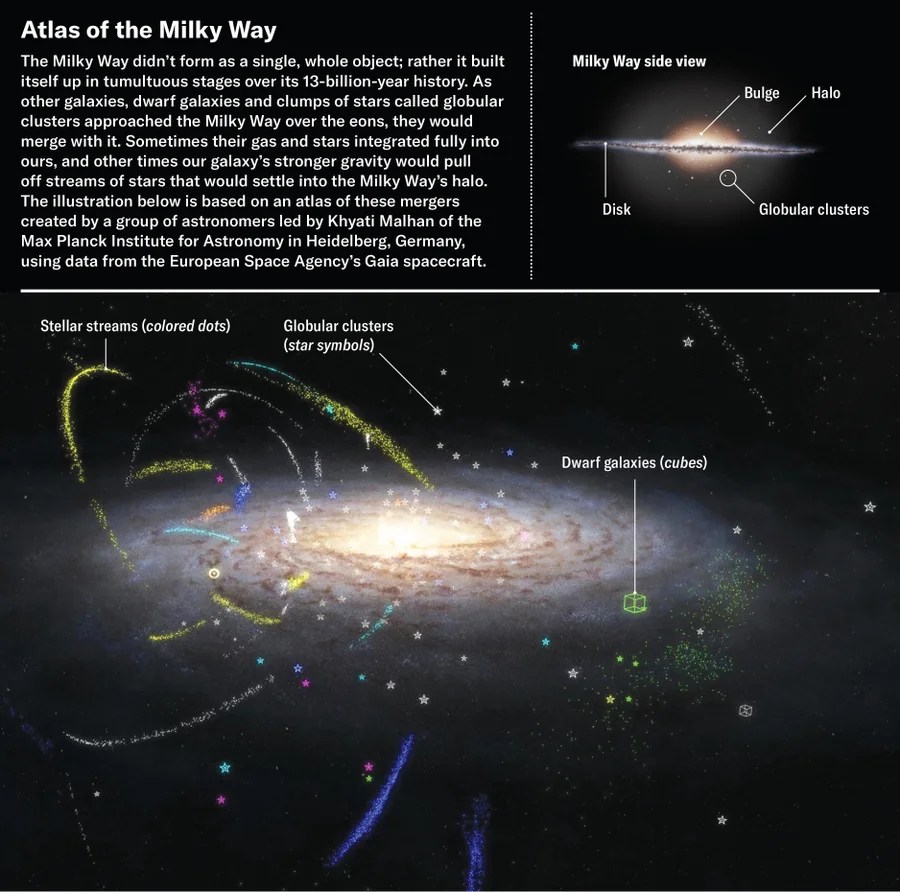

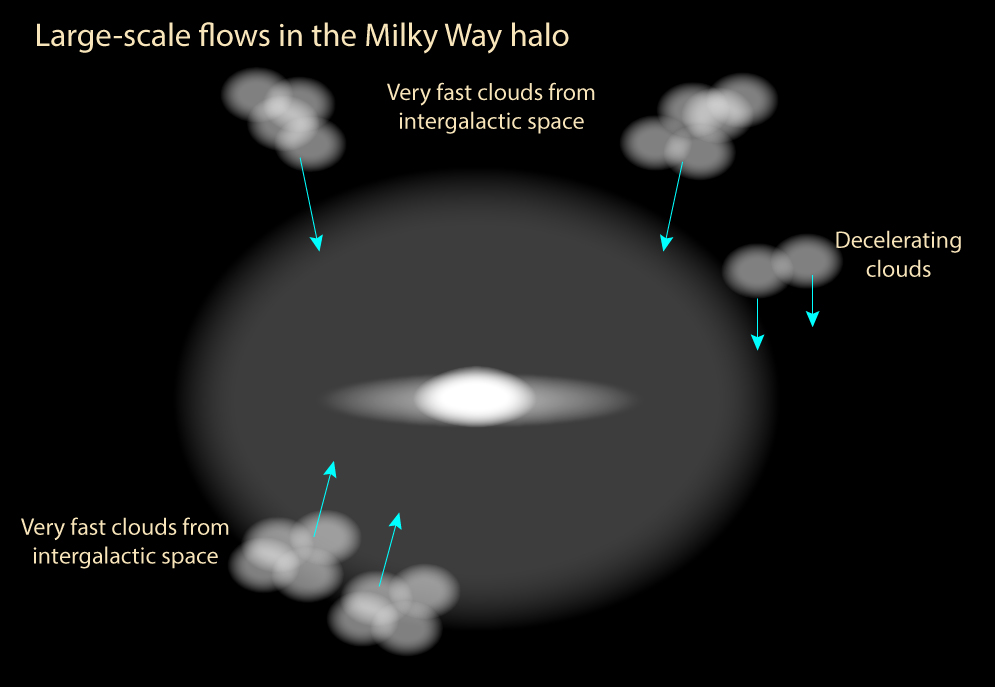

Above, you see our home galaxy, the Milky Way. But it’s not a single, solid object, and it didn’t form as one. It’s a mishmash of material that’s fallen into its gravitational pull over billions of years.

In our night sky, we can see the evidence of that material in stellar streams — great streamers of stars left behind like breadcrumbs as smaller galaxies were gobbled up by the Milky Way.

Here are just a few examples, as viewed from Earth:

See all those little trails of speckles?

Yup — those are our stellar streams. Each of these trails forms a little arc, part of the orbit that these smaller galaxies have taken as the Milky Way slowly stripped their stars away.

Now…see the label sort of left of middle in the diagram, “stream of M92”?

M92 is a globular cluster…

…and it’s not the only one in orbit of the Milky Way.

In fact, globular clusters are quite common in the galactic halo, a part of the galaxy’s structure that extends above and below the disk. And they are, in a word, weird.

They’re really old. And by that, I mean really, seriously old.

I’m talking about billions of years — some, almost as old as the universe itself.

But…how can we tell?

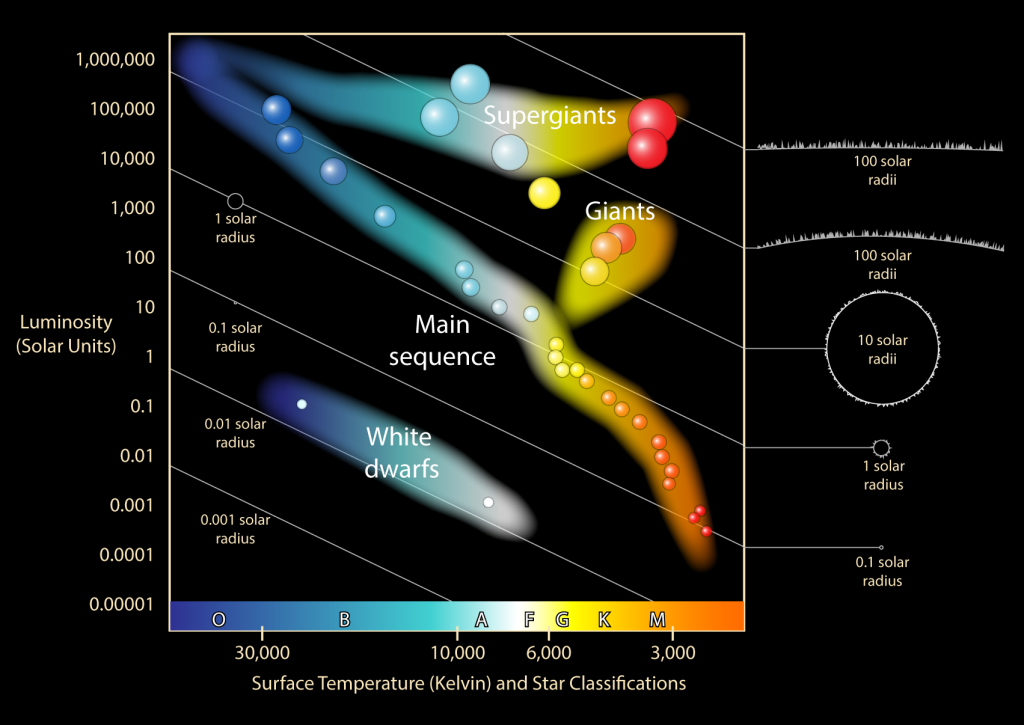

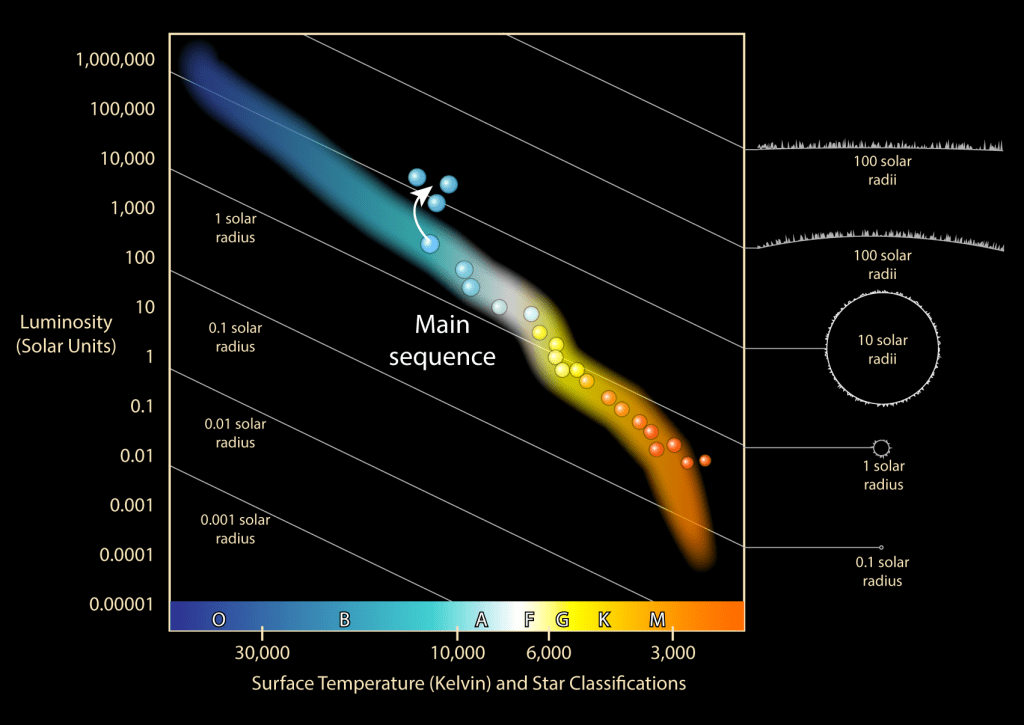

Alright, time to take a trip back through this blog’s archives…to our old friend, the H-R diagram.

As I’ve said before on this blog, this is probably the single most useful tool you will ever encounter in stellar astronomy.

This diagram sorts stars. But that’s not the coolest thing about it.

The power of this diagram is in the way it relates all the properties of a star — temperature, luminosity, magnitude, radius, mass. It demonstrates that all these details are interrelated. That for any one star, by measuring just two, you can find the rest.

And, by relating all those details, the H-R diagram reveals even more: the star’s age and expected lifespan. From there, we can make uncountable predictions. It opens up a whole world of questions and possibilities.

…but let’s focus on what we can learn about globular clusters, shall we?

First, take a look at the “main sequence“: the band of stars that crosses from the upper left to lower right.

These are “stable” stars. That is, stars that are fusing hydrogen nuclei in their cores.

Now, look at the “upper” main sequence — the blue region of that band.

Note where these stars are plotted, relative to the “temperature” axis. Their surface temperature is tens of thousands of Kelvins. That’s still tens of thousands in Celsius (and upwards of 20,000°F, for the Americans).

That’s just the surface. The core of a star is exponentially hotter than that. Such a star burns hot and bright — no surprise that we find it so high on the “luminosity” axis! But, more importantly, these stars live very short, explosive lives.

They will be the first to burn though their hydrogen fuel, lose stability, and leave the “main sequence.”

They’ll join the ranks of “supergiants” up at the top right: stars whose outer envelopes (or, in plain English, atmospheres) have expanded to hundreds of times the size of the sun.

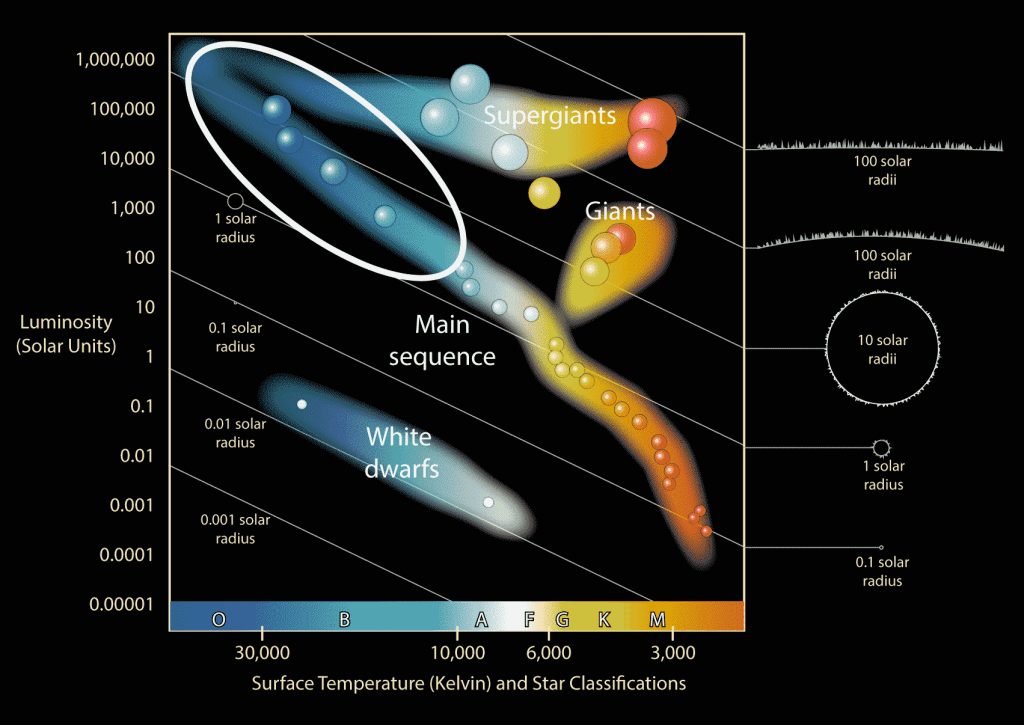

Now, what if we could take a look at a globular cluster…and plot all of its stars on the H-R diagram?

We’d get this:

Keep in mind that this is a plot of just the stars in one globular cluster.

And they’re all pretty low on the main sequence.

Cooler stars are still present, though. These stars don’t burn through their hydrogen fuel as quickly, and they can remain stable much longer.

Here’s the crux:

The minimum age of the stars present shows us how old the cluster must be.

So, this globular cluster is at least old enough for all the hot blue stars to have evolved into giants.

But how do we know that’s unusual?

Let’s compare globulars to the other common type of star cluster: open star clusters.

Meet the Pleiades, also known as Messier 45:

Note the bright blue color of the stars. For stars, color isn’t a coincidence. Can you guess where they’ll be plotted on the H-R diagram?

Yup, you guessed it…

The Pleiades H-R diagram may not have the hottest of stars, but it actually has blue stars — which is more than we can say for globular clusters.

(It’s not that unusual to be missing the hottest stars — such stars are extremely rare, and barely stable. They only last on the main sequence for a blip in cosmic time.)

You can see that the turnoff point — the little white arrow, showing which types of stars have begun to leave the main sequence — is a bit higher up in the diagram.

Now, let’s take a look at globular clusters and open clusters visually…

They don’t look much alike, do they? Globulars are quite compact and round, while open clusters are spread out and more, well, open.

By the way, I used to think that “globulars” got their name from the word “glob,” pronounced “glahb” — as in, they’re a big globby bunch of stars. But it actually comes from the word “globe” (“glowb”). As in, they’re spherical, like the Earth. And there’s nothing spherical about open clusters.

Galaxies, on the other hand…

Well, let’s take a look at how globular clusters compare to galaxies, shall we? Specifically, let’s compare a globular cluster to a galactic nucleus. In the photo below of Andromeda, the galaxy’s disk is too faint to see.

Huh. They both look kinda compact and…globe-ular.

Can that be a coincidence?

As it turns out…it’s not!

But this is a story that starts billions of years ago…in fact, 400 million years after the Big Bang, in the time of “cosmic dawn,” when the universe’s first stars had just begun to burn.

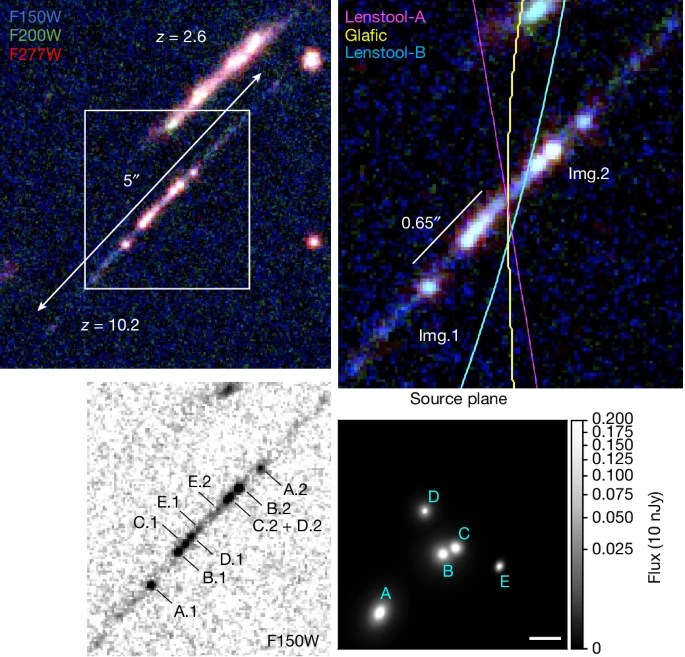

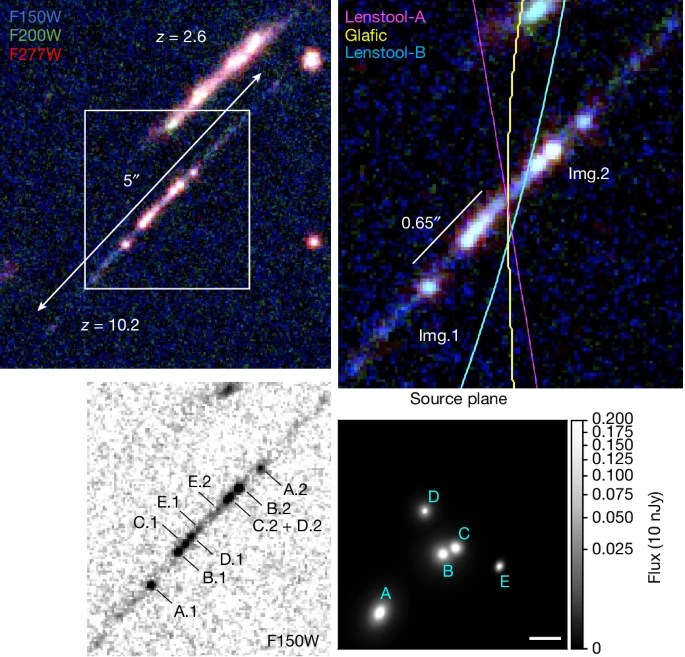

Meet the Cosmic Gems:

See in the top-left image, the streak in the white box?

These may be the earliest star clusters yet discovered.

But…wait a second. They don’t look much like star clusters, do they? How come they’re so…well…streaky?

This is actually an effect of gravitational lensing. In fact, that gravitational lensing is why we’re able to see these clusters at all. We see them as they appeared at cosmic dawn thanks to a very useful mechanic of light: it takes time to travel.

When observing objects in our own cosmic neighborhood — such as nearby galaxies — astronomers have to contend with the fact that we can never observe objects as they appear right now. For example, we see the moon as it appeared when the light entering our eyes left it, roughly 1.3 seconds ago.

1.3 seconds isn’t much, but that difference compounds as you look farther and farther away. Even within our own galaxy, we see its most distant stars as they appeared 52,000 years ago.

When trying to piece together the story of the universe, though, that mechanic of light becomes very useful. It means that by peering farther and farther into the depths of the cosmos, we look back in time.

At a redshift of 10.2, the Cosmic Gems are the most distant star clusters yet discovered, and therefore, the earliest.

But star clusters are much smaller and fainter than galaxies, and especially hard to spot at such great distances.

We’re only able to study the Cosmic Gems thanks to gravitational lensing:

Gravitational lensing allows us to make out far greater detail than we normally would for distant, faint objects. But it has a bit of a side effect…

…it tends to distort the image.

It can mirror an image, causing a galaxy or star cluster to appear in multiple places — like the blue galaxy you see in the top left, below (Cl 0024+17). Believe it or not, all the little splashes of blue in that image are the same galaxy.

You see a similar effect in the top right, below (MACSJ0138.0-2155) — another blue galaxy mirrored, but with just two images, this time. More obvious is the way an elliptical galaxy has been drawn out into orange streaks like comets…

…or the effect could draw a spiral galaxy out into a long squiggle, like you see in the bottom image (Abell 370).

That’s what’s going on with the Cosmic Gems. They may appear as streaks, but trust me, they’re star clusters.

But more importantly…

They’re really dense.

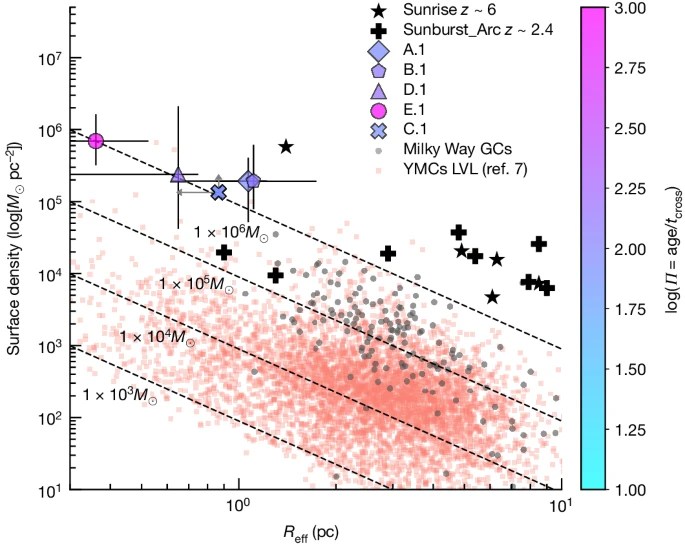

Just for fun, here’s the super mathy graph of it, straight from the primary source article:

I don’t expect you to make much sense of this. It’s just short of being raw, messy data. The important thing is, these guys are very compact.

In fact, if the Cosmic Gems have survived to the present day…they could now resemble globular clusters.

In other words, perhaps these are globular clusters. Perhaps we’re seeing what Messier 13 — and others like it — looked like around the time of cosmic dawn.

You realize what that means?

When galaxies formed later — at least a few million years after cosmic dawn — the Cosmic Gems would have been available ingredients.

But if the Cosmic Gems and globular clusters are one and the same…does that mean globular clusters were ingredients in the first galaxies?

How do you build a galaxy, anyway?

We need to go back in time again — to the first 30 minutes after the Big Bang.

In this time, the radiation in the universe was denser than that of matter. Constant interaction with radiation kept matter scattered and prevented it from clumping together under its own gravity.

But dark matter doesn’t interact with light. That’s why we can’t see it. Radiation had no power over it. It would have been able to clump together much earlier on…

…and form the first black holes.

In fact, astronomers suspect that these may explain the first quasars: those erupting black holes detected at such great distances that the typical cause — interacting host galaxies — shouldn’t have even formed yet in the universe.

Now, here’s where it gets interesting.

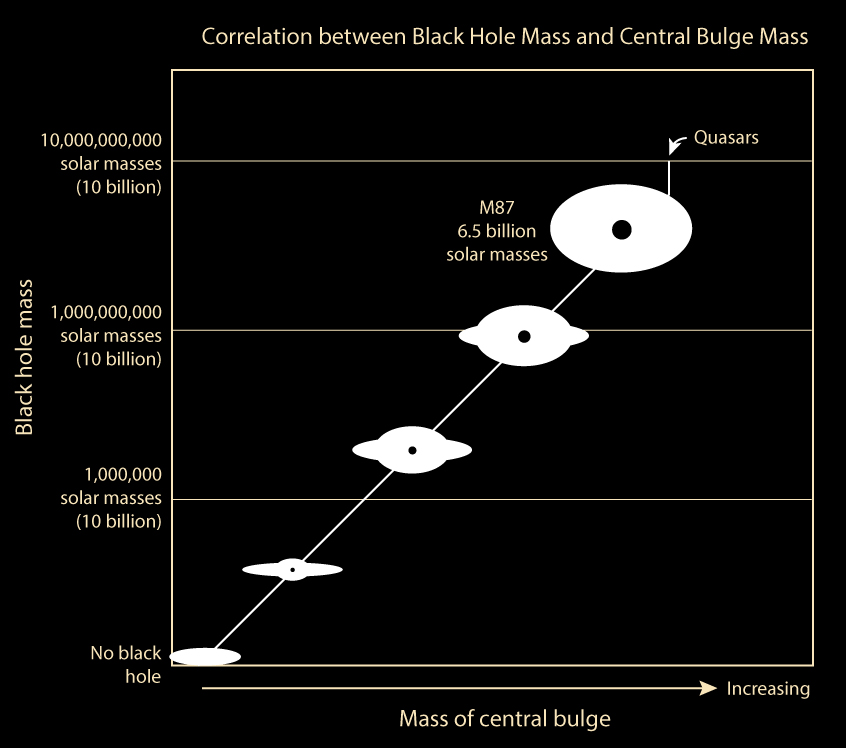

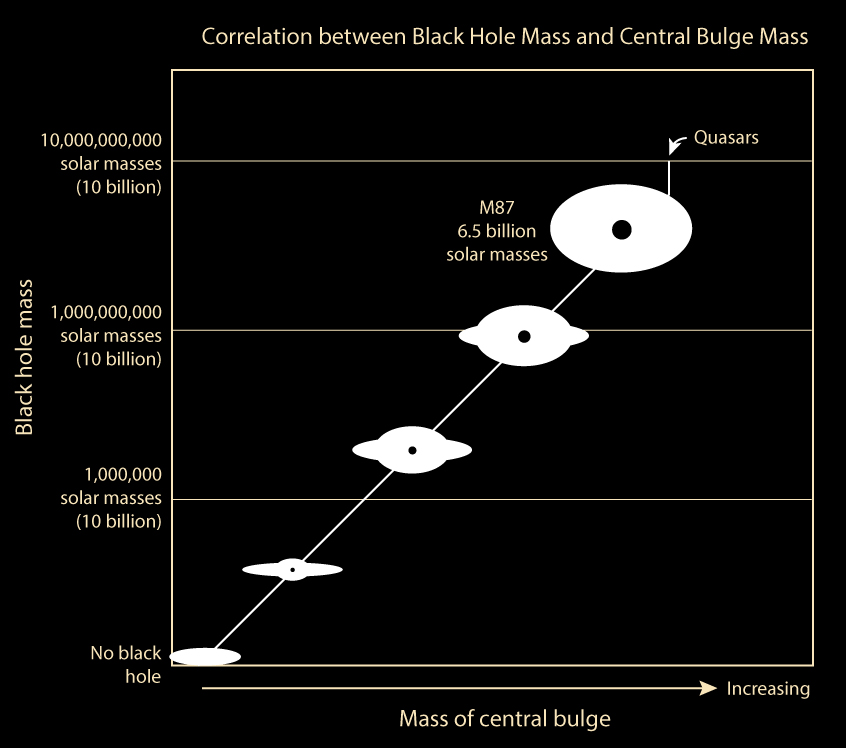

There is strong evidence that most galaxies — at the very least, most large galaxies — contain supermassive black holes. We’re talking about black holes with the mass of more than tens of thousands of suns (solar masses).

These supermassive black holes reside in the center of their host galaxies. And astronomers have observed that their masses correlate to the mass of their host galaxies’ nuclear bulges…

…which indicates that galactic nuclei and their supermassive black holes form together.

These black holes wouldn’t have started out supermassive, though. They would’ve grown from something smaller.

But what?

Well…let’s take a look at none other than Omega Centauri, the brightest globular cluster in the night sky.

Yup — a globular cluster!

This globular cluster is home to a unique cosmic specimen: an intermediate-mass black hole.

Now, the lower mass limit for a supermassive black hole is tens of thousands of solar masses. The mass range for an intermediate-mass black hole overlaps that a bit: 100 to 1 million M⨀ (solar masses).

Omega Centauri’s black hole, however, falls firmly in the intermediate range at only 8200 M⨀.

It’s less than the lower mass limit for a supermassive black hole. It can only be an intermediate-mass black hole.

What does this mean?

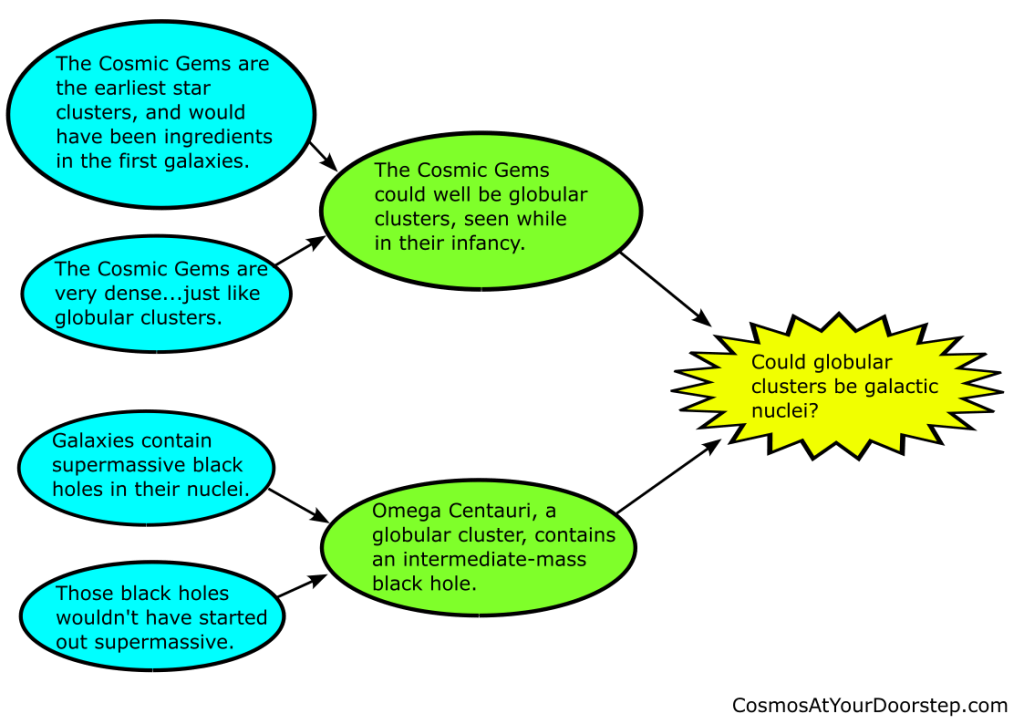

Let’s round up the evidence so far…

The Cosmic Gems — the earliest star clusters — might well be early globular clusters, and we know that they were ingredients in the first galaxies. That would seem to indicate that globular clusters were ingredients in the first galaxies.

We know that most galaxies today contain supermassive black holes.

We also know that those supermassive black holes would have grown from something smaller.

We’ve detected one such something — an intermediate-mass black hole — in a globular cluster.

That could mean that globular clusters weren’t just ingredients — they are the galactic nuclei themselves.

The visual evidence would seem to support that conclusion…just look again at the resemblance between Andromeda’s nuclear bulge and a globular cluster.

But if globular clusters are galactic nuclei, that leaves us with a massive question…

What the heck happened to the rest of the galaxy? Why’s it just the nucleus?

Well, let’s not forget the big picture here. Remember when I showed you the Milky Way and its many satellites?

Here it is again:

Before we started investigating globular clusters, we discussed stellar streams.

One such stellar stream — the Sagittarius Star Stream — still arcs several times around the Milky Way, revealing the path taken by the Sagittarius Dwarf Galaxy.

You see, billions of years ago, a small dwarf galaxy was pulled into orbit around the Milky Way. It was too small to withstand the strong tidal forces from the much larger Milky Way, so it was stripped apart, leaving a star stream behind.

But here’s the cool bit. The Sagittarius Dwarf itself is long gone, but its surviving core is still visible…

…as Messier 54.

That’s one way that a galaxy can be stripped down to just its nucleus, until it appears to us today as a globular cluster.

It’s not the only way, though, and Omega Centauri’s intermediate-mass black hole gives us another clue…

Remember when I said that the supermassive black holes in galaxies today wouldn’t have started out supermassive?

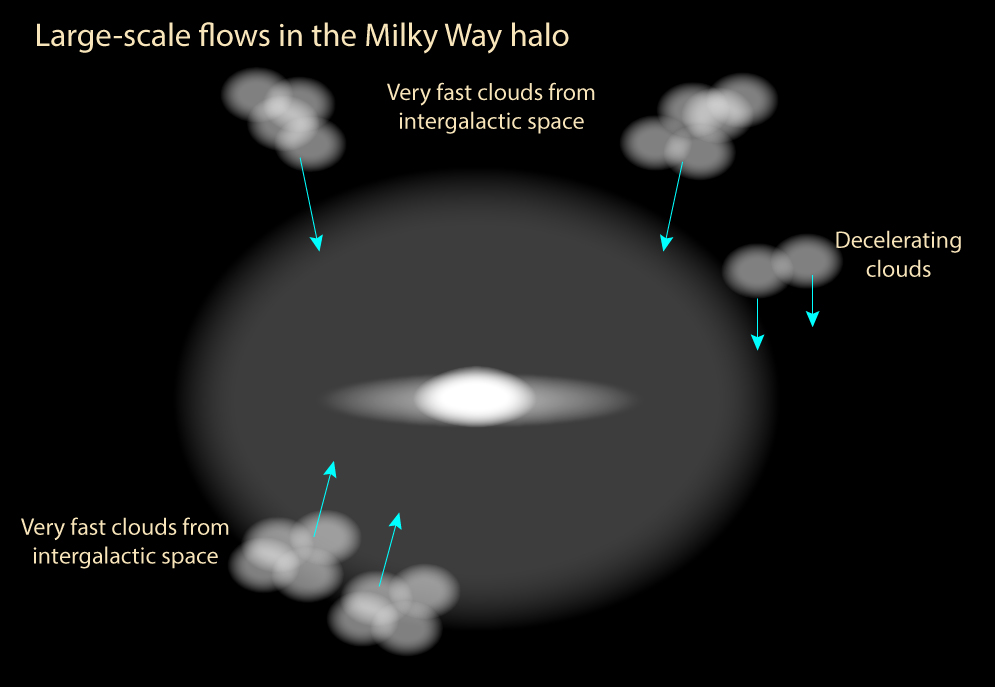

Well, galaxies’ nuclei form together with their central black holes, but the rest of the galaxy doesn’t. The rest of the material is added later, as material from outside gravitates toward the forming nuclear bulge…

Clouds of material will swirl in toward the forming nuclear bulge like water toward a drain, and eventually take the shape of the Milky Way’s spiral arms.

That’s what would’ve happened for our nearest galactic neighbor, Andromeda, and our own Milky Way — as well as for countless galaxies like them.

But what happens if that doesn’t work?

What happens if something stops material from accumulating, and “finishing” the galaxy-building process?

That’s totally possible.

See, galaxies don’t generally exist in isolation. They’re found in clusters, and they often interact gravitationally.

This can completely distort their shapes, as in the case of the “Mice”…

…or it can prevent infant galaxies from ever gathering enough material to “mature.”

That’s what happened with Omega Centauri.

You can’t strip a black hole of mass, so this globular cluster’s intermediate-mass black hole is evidence of stunted growth.

In other words…we’re looking at an infant galaxy frozen in time, before it ever had a chance to finish growing its nucleus and begin collecting material for its disk.

Okay, but…what about Messier 54? Does it have an intermediate-mass black hole? Do all globular clusters? What happens if we discover that they don’t — does that punch a hole in our hypothesis?

Not necessarily.

Meet UGC 4879:

This is a dwarf galaxy. It’s much smaller than the Milky Way. And like others of its kind, it doesn’t have a central black hole.

You don’t need a black hole to make a galaxy.

In fact, any galaxy — with or without a central black hole — can be stripped down to its nucleus due to tidal interactions, just as long as there’s a bigger galaxy nearby to do it.

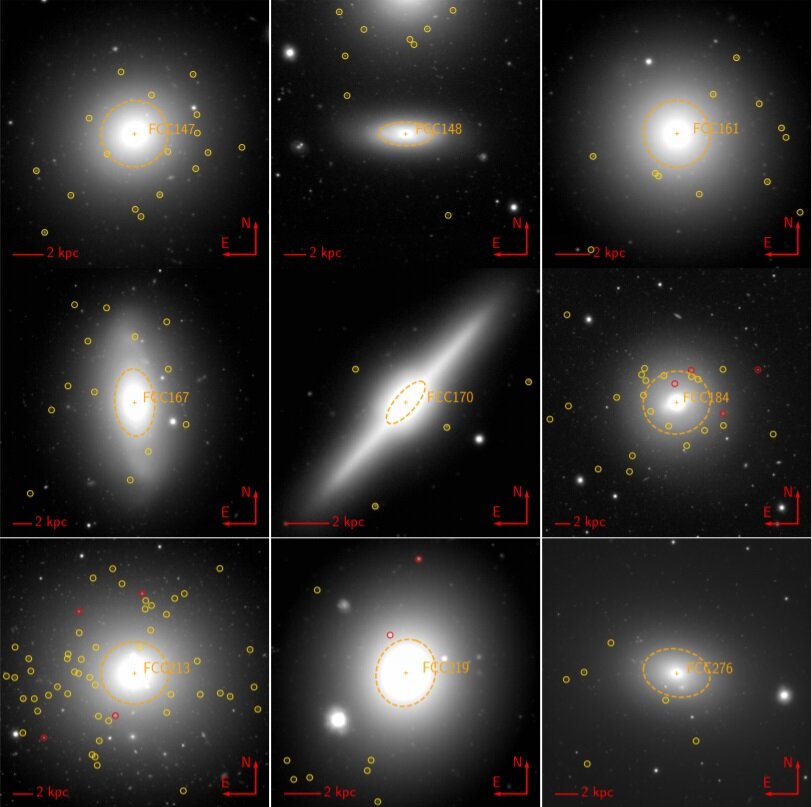

That would seem to be the case with ultra-compact dwarf galaxies:

Like the Cosmic Gems, these objects resemble globular clusters. But unlike the Cosmic Gems, they are not star clusters. They are galaxies that have been stripped of their stars, leaving just their nucleus.

Sound familiar?

It should — but it gets better. Because while some of these galaxies resemble globular clusters, others more strongly resemble a different type of star cluster: nuclear star clusters.

What’s a nuclear star cluster, you ask?

It’s the central star cluster of a galaxy. Any galaxy. Some reside within proper galactic nuclear bulges and have central black holes. Others are the center of gravity for smaller galaxies with no central black hole.

And it looks quite a bit like a globular, too, doesn’t it? Just a bit less round and compact.

So let’s put the pieces together.

400 million years after the Big Bang, cosmic dawn began. The first black holes already existed — formed from dark matter, which got a head start on clumping together.

From this point, there were likely two main processes for galactic evolution.

First, let’s follow the process involving black holes:

As we know, those first black holes would have gathered material from what was available around them. The Cosmic Gems — and other early star clusters — may have grown this way.

The black holes and their orbiting material would have grown together, into the first nuclear bulges…

…and when their black holes reached around 8000 M⨀, they would have resembled objects like Omega Centauri.

If they interacted too much with other nearby galaxies, they might have stopped there, their growth stunted, frozen in time. Or, if they continued undisturbed, their black holes would have eventually grown into supermassive black holes…

…and they would mature into a proper nuclear star cluster, of the variety containing central black holes.

They would then have the chance to begin pulling in clouds from the intergalactic space around them, building their disk…

…and, today, they might resemble objects like the Andromeda galaxy: full spirals in all their splendor.

On the other hand, if their growth was interrupted while they were building their disk, their growing envelope of stars would have been slowly stripped away…

…leaving an ultra-compact dwarf galaxy, of the variety containing supermassive black holes (some do).

Now, let’s follow the second process, the one that doesn’t involve black holes.

All the while galaxies were being built around the first black holes, stars would have also begun to clump together on their own — forming star clusters without black holes.

The Cosmic Gems may have formed in this way, instead — I don’t know that we have data on whether those specific clusters contain black holes.

Either way, these would have formed nuclear star clusters of the black-hole-free variety…

…and they would have grown into the first dwarf galaxies.

Many of these galaxies are still visible today. But, equally, many of them would have fallen into orbit around larger galaxies…

…just like what happened with the Sagittarius Dwarf.

These dwarf galaxies would have been stripped to their cores, leaving behind black-hole-free globular clusters like Messier 54.

So, that’s why we see the objects we do in the present day. Ultimately, globular clusters are the nuclei of galaxies. Some of them have black holes; others don’t.

In another life — so to speak — those with black holes would have grown into magnificent spirals like the Milky Way. But something stopped them: either their growth was stunted early, and they are frozen in time, or they did manage to accumulate a bit of a disk but were stripped down by a larger, nearby galaxy.

As for those without black holes — these were once dwarf galaxies. But they have since fallen into orbit around larger galaxies and been devoured, their stellar envelopes dusted through space as stellar streams.

And there you have it, people: the most complete story of galactic evolution I can offer you! I can’t tell you how excited I’ve been to share this one, ever since I saw the newest research emerge.

Next up, we’ll have five more posts rounding up the concepts in cosmology and connecting the dots. And then, finally, we’ll move on to the planetary sciences!

Did I blow your mind? 😉