Aaaaand she’s back! Sorry for the delay — school had me burnt out!

Consider this: humanity has existed for just a few thousand years, and for most of that time, our existence has been constrained to one little blue mote of dust, suspended in a sunbeam.

And yet, we’ve been able to piece together 13.8 billion years of our universe’s history.

There’s still a lot we don’t know. Dark matter and dark energy remain the greatest of cosmic mysteries. 95% of the universe remains undiscovered.

But we understand the broad strokes. We understand that we live in an expanding, infinite universe, in a galaxy we call the Milky Way, on the surface of a terrestrial world we call the Earth.

It’s a far cry from where we began: 4000 years ago, with the assumption of a flat Earth at the center of an unchanging universe.

That, I think, is the true wonder of astronomy. And today, I want to shine a spotlight on the march of scientific progress that brought us here.

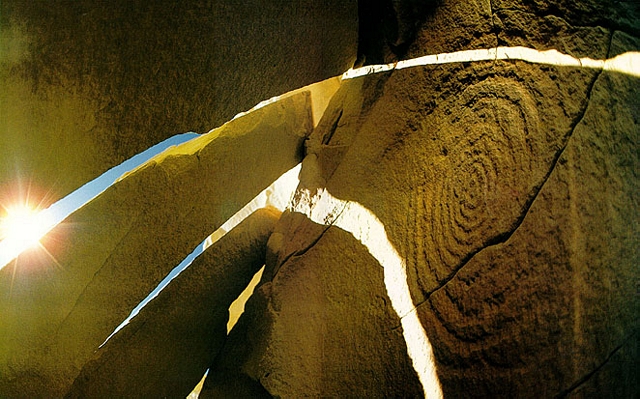

3200 BCE: Newgrange, Ireland

Newgrange is thought to be a tomb, but this hypothesis is uncertain. More obvious is the way its main passageway is lined up with the winter solstice sunrise.

3000-2000 BCE: Sumer and Babylon

The Sumerians and Babylonians invent several of today’s 88 official constellations: Scorpius, Leo, Sagittarius, Taurus, Auriga, Gemini, and Capricorn.

3000-1800 BCE: Stonehenge, Salisbury Plain

Stonehenge is one of my all-time favorite sites for archeoastronomy: the study of how ancient cultures viewed the night sky. And it’s one of many examples.

Stonehenge in particular is full of countless astronomical alignments. Imagine: this early on, humans are fascinated by the night sky enough to build monumental stonework.

668-627 BCE: Babylonian Star Calendar

The Babylonian calendar combines a solar and lunar cycle so that the beginning of the year remains close to the spring equinox.

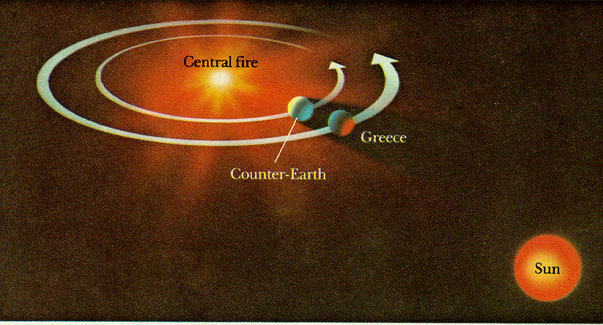

5th Century BCE: Philolaus

Philolaus is the first of the ancient philosophers to suggest that the Earth moved — in a circular path around a central fire.

…which is surprisingly on-point for his time. His model only breaks down when he specifically mentions that this central fire is not the sun, and we can’t see the central fire because there is a “counter-Earth” in the way.

428-347 BCE: Plato

Plato single-handedly reels the study of astronomy backward…

…by arguing that human observations are distorted and misleading, and only pure thought can lead to true conclusions.

He basically dismantles any early conception of the scientific method.

400 BCE: Babylonian Calculations

While Plato is busy reeling astronomy backward in Greece, Babylonian astronomers accurately calculate the exact date and time of each month.

384-322 BCE: Aristotle

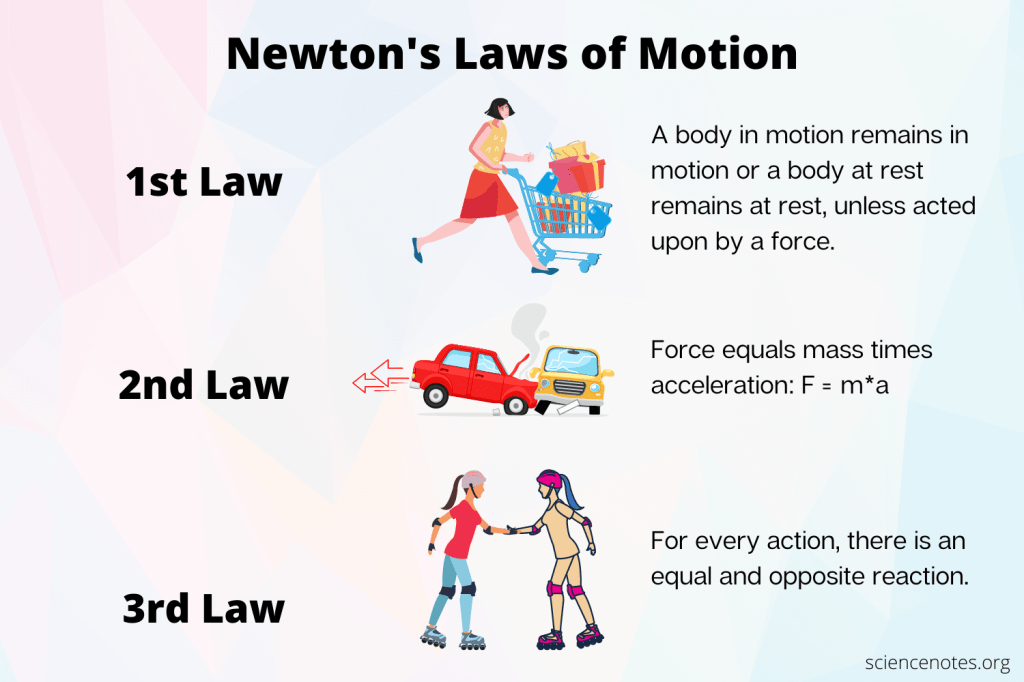

With regard to science, Aristotle has two main teachings: the geocentric model of the universe with uniform circular motion, and the four classical elements.

Aristotle holds that the four elements — earth, water, air, and fire — each tend to return to their “proper place.” Motion toward a proper place is “natural motion” and requires no force. Motion away from a proper place is “violent motion” and requires a force to be applied for as long as the motion takes place.

Mid-2nd Century BCE: Hipparchus

As a classical astronomer, Hipparchus’s most important work concerns the study of eclipses.

Like most classical astronomers, he assumes a geocentric (Earth-centered) universe.

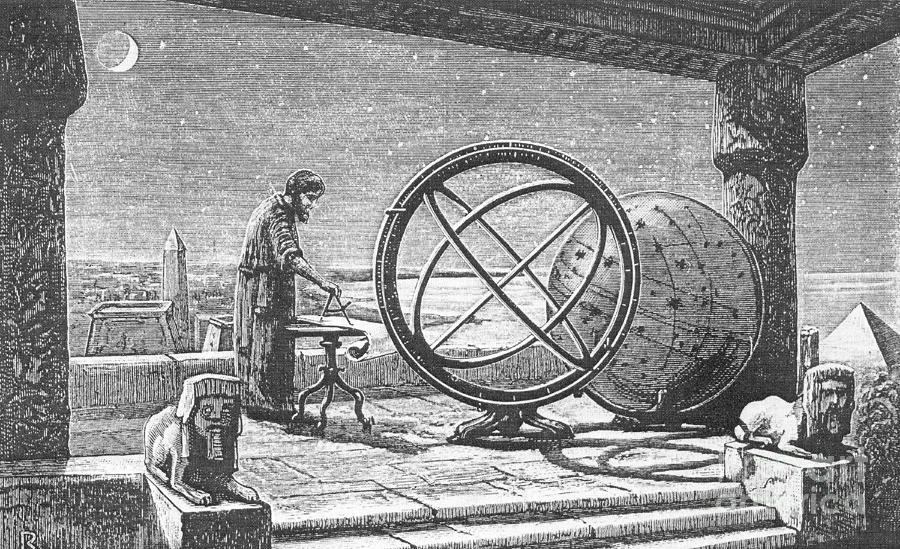

0 CE: Temple of Isis, Egypt

One of the world’s earliest observatories, Temple of Isis is built to line up with the star Sirius as it rises.

Sirius is a significant star at many ancient sites, and it’s no wonder — it is, after all, the brightest star in the night sky.

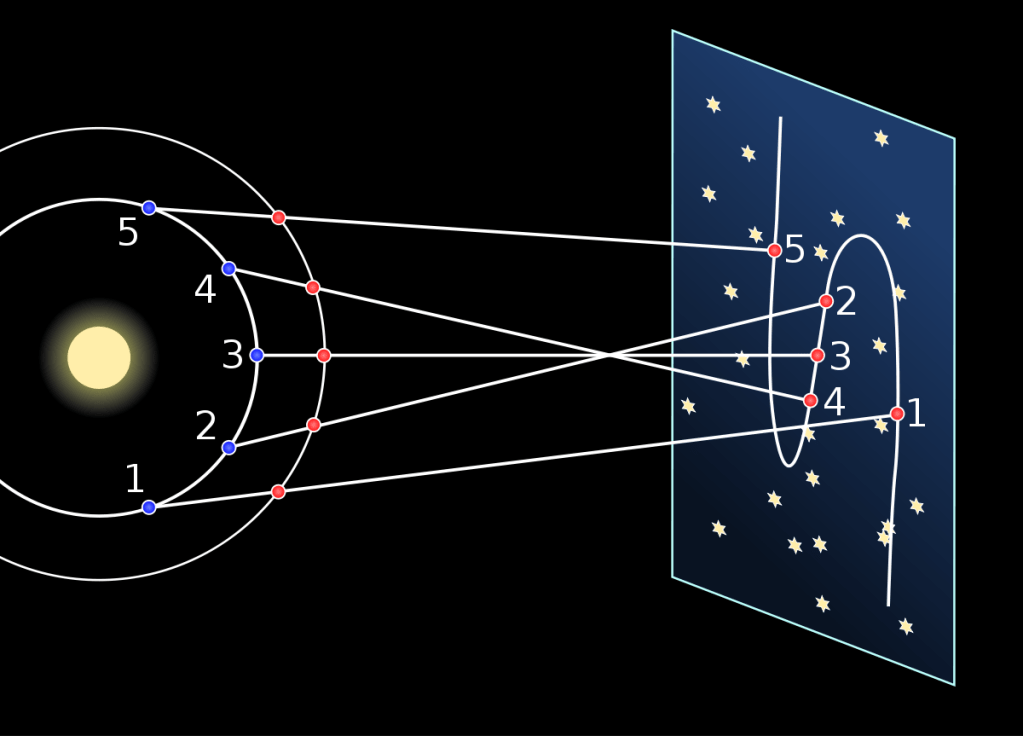

150: Claudius Ptolemy

In “The Almagest,” Ptolemy attempts to explain retrograde motion — the tendency of the planets to briefly move backwards — with epicycles.

His model of the universe is geocentric, but he is the first to suggest that Earth is not at the exact center.

900: Sun Dagger, Fajada Butte, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico

Fajada Butte sports a “sun dagger”: a dagger of light cast across a spiral carved into a rock face, which shifts with the seasons.

The butte is initially open to the public, but is later closed when soil erosion noticeably shifts the rocks and changes the position of the sun dagger.

Before 1385: Geoffrey Chaucer

One of the earliest uses of the term “galaxy” can be found in Chaucer’s poem “The House of Fame”:

Se yonder, loo, the Galaxie,

Which men clepeth the Milky Wey,

For hit is whit

Which translates from Middle English to:

See yonder, lo, the galaxy,

which they call the Milky Way,

because it is white

1508-1543: Nicolaus Copernicus

Copernicus suggests something revolutionary: what if the Earth is not the center of the universe?

The heliocentric — sun-centered — model quickly gains traction because it can do what no previous model can: explain retrograde motion simply and elegantly.

But it still has serious problems. It places the sun at the exact center of the solar system and the universe, which is inaccurate. The planets do not orbit in perfect circles, and the sun isn’t the center of the universe at all.

As such, the heliocentric model can’t predict planetary motion any better than Ptolemy’s epicycles, and Copernicus delays publishing until 1543, the year of his death.

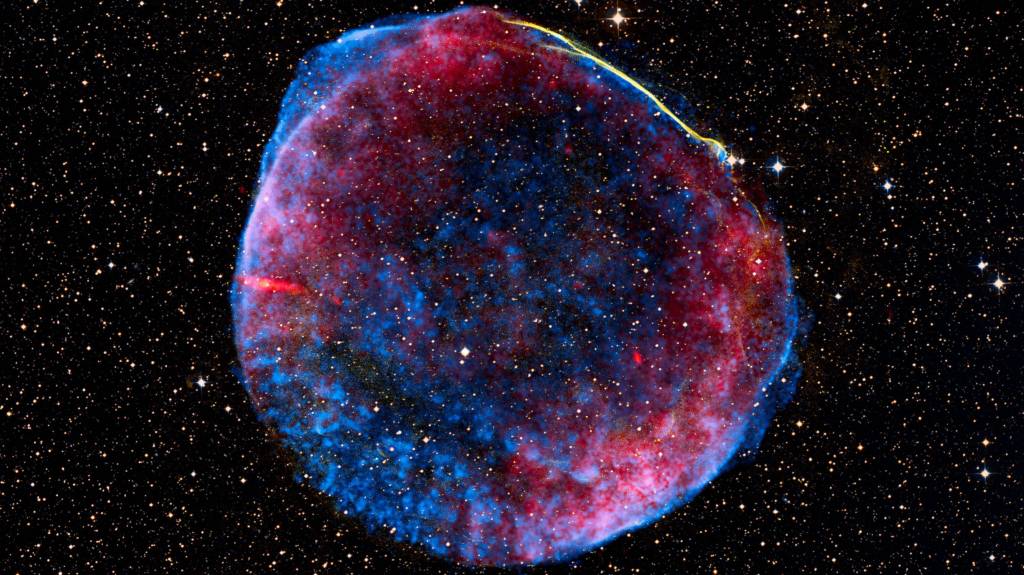

1572: Tycho Brahe

Tycho rejects the heliocentric universe. But he makes one critical observation that will move the study of astronomy forward by leaps and bounds.

He observes a supernova — to the classical astronomers, a change in the heavens.

This is the first nail in the coffin of Aristotle’s uniform circular motion, and will pave the way for contributions from Galileo and Kepler.

Tycho also makes an extensive catalog of precise astronomical observations, which will be critical for Kepler’s work.

1589: Galileo Galilei

Galileo performs the first true scientific experiments — and his results fly directly in the face of Aristotle’s teachings.

Aristotle would have said that a heavier object is made of more earth and would be driven to return to its proper place faster (fall faster).

But Galileo shows that weight doesn’t matter. All objects fall with the same constant acceleration.

1609-1619: Johannes Kepler

Kepler is the first to figure out his model of planetary orbits mathematically. And he determines that orbits are not perfectly circular, but elliptical.

This is classical astronomy’s greatest advancement since Copernicus’s heliocentric model: the dismantling of Aristotle’s uniform circular motion.

Kepler has accurate data to work with thanks to Tycho’s extensive and precise observations.

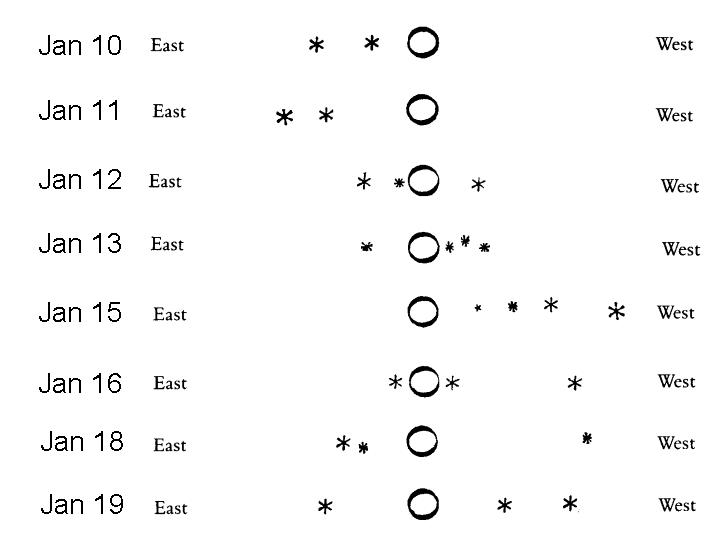

1610: Galileo Galilei

In the midst of Kepler’s work with planetary motion, Galileo builds a telescope — though he does not invent it — and makes several critical observations.

One, the sun is imperfect. It has “blemishes,” which we will come to call sunspots.

Two, the moon is imperfect. It has geological features like the Earth.

Three, Jupiter has moons. No one has previously considered that there might be a center of motion in the universe other than the sun or the Earth.

Four, the band of stars sprinkled across the sky — known as the Milky Way — contains far more stars than can be seen with the naked eye.

1687: Isaac Newton

Standing on the shoulders of giants, Newton devises his three laws of motion. He also devises the law of universal gravitation.

Newton’s discoveries usher in a new age: one in which humanity begins to apply science and mathematics, rather than philosophy, to understand the natural world.

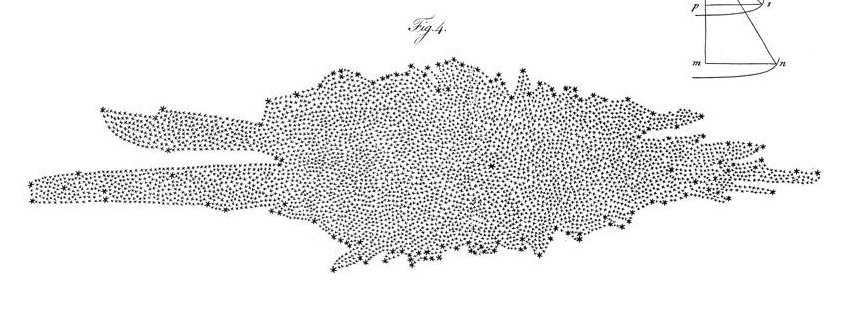

1750: Thomas Wright

Astronomers realize what the shape of the “Milky Way” in the night sky means: it wraps around the entire sky, so it’s easy to imagine that humanity — that is, Earth– is sitting in the middle of a disk of stars.

We begin referring to this disk of stars as the “star system,” and it is all we know of the universe.

More than a century after Galileo’s observations of the sheer number of stars in the Milky Way, Thomas Wright refers to it as a “grindstone universe,” comparing it to the technology of the time.

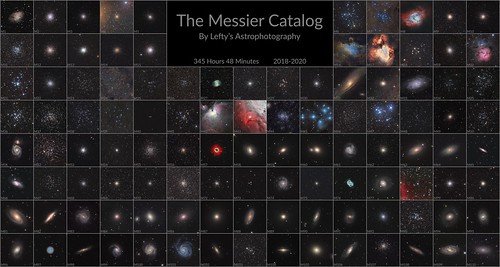

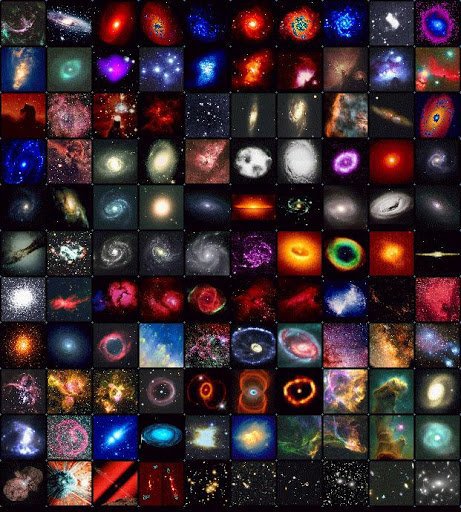

1774: The Messier Catalog

Everything in the night sky revolves around the north star in the same way…except for solar system objects.

Planets and comets are identifiable by the fact that unlike any other object, they change position relative to the background stars.

In his search for such an object, Charles Messier compiles a catalog of 110 fuzzy-looking objects that do not change position night to night — a catalog of deep-sky objects like nebulae and galaxies that becomes known as the Messier Catalog.

Still, no one is calling anything a “galaxy” yet. We don’t even know we live in one.

1783-1802: The Herschels

William and Caroline Herschel use a method they call “star gauging” to determine the shape of our own “star system,” which we call the Milky Way.

They count the number of stars visible in different directions. Unbeknownst to them, dust clouds obscure their view to the edge of the star system, and they come up with a size that is far too small.

1780-1872: Mary Somerville

Somerville experiments with magnetism and produces writings on astronomy, chemistry, physics, and mathematics. Her translation of astronomer Pierre-Simon Laplace’s The Mechanism of the Heavens is used as a textbook well into the next century.

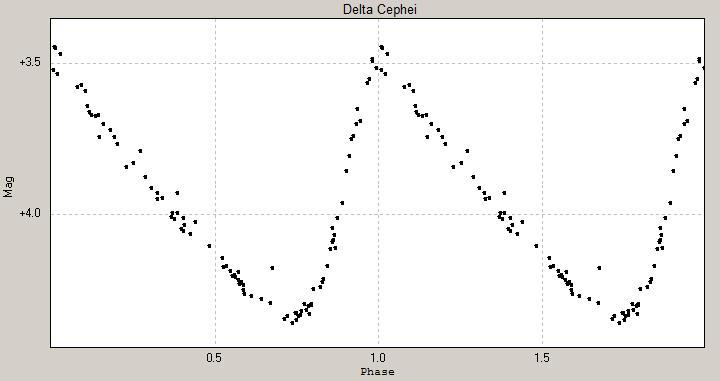

1784: John Goodricke

Delta Cephei is the fourth brightest star in the constellation Cepheus — and the first of its class to be discovered.

19-year-old English astronomer John Goodrich notices that Delta Cephei periodically varies in brightness. This will pave the way for Henrietta Leavitt’s work over a century later.

1810-1864: The Herschels (Again)

William and Caroline Herschel compile thousands of astronomical observations — including their own — into a new catalog of deep-sky objects.

By 1810, the catalog includes 2500 objects. By 1864, it includes 5079 objects.

1845: William Parsons

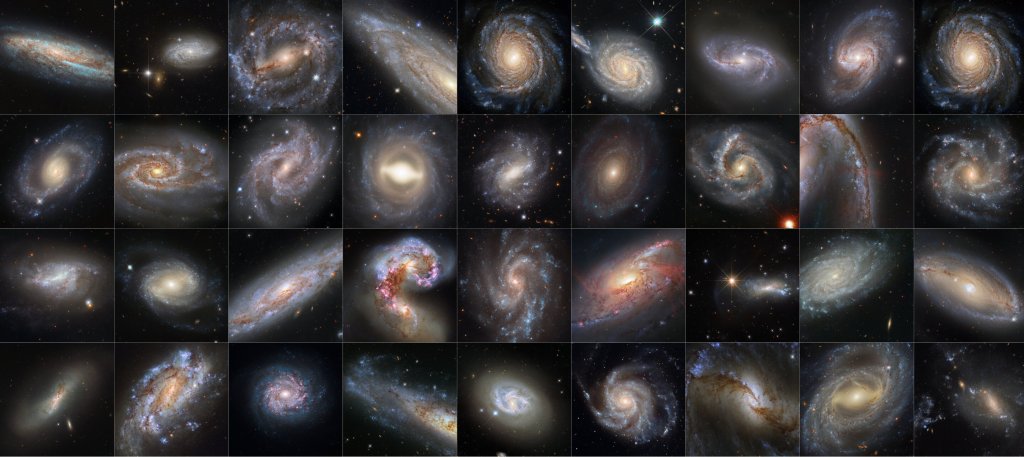

With his 72-inch telescope — at the time, the largest in the world — William Parsons, third Earl of Rosse in Ireland, sketches his observations of faint, blurry objects that he calls spiral nebulae.

One of these will come to be called the Whirlpool Galaxy.

Parsons welcomes Kant’s notion of “island universes” (apparently). Perhaps that explains his “spiral nebulae.”

(I have not found a source confirming my textbook’s assertion on the matter — or even one confirming the origin of the term “island universe.”)

1847: Maria Mitchell

Mitchell discovers a comet through her telescope, earns a medal from the king of Denmark, and is the first woman to be elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

1888: John Louis Emil Dreyer

Dreyer publishes data from 50 sources, including the Herschels’ work, as the New General Catalog, or NGC.

The NGC catalog is complete with 7840 objects.

1905: Albert Einstein

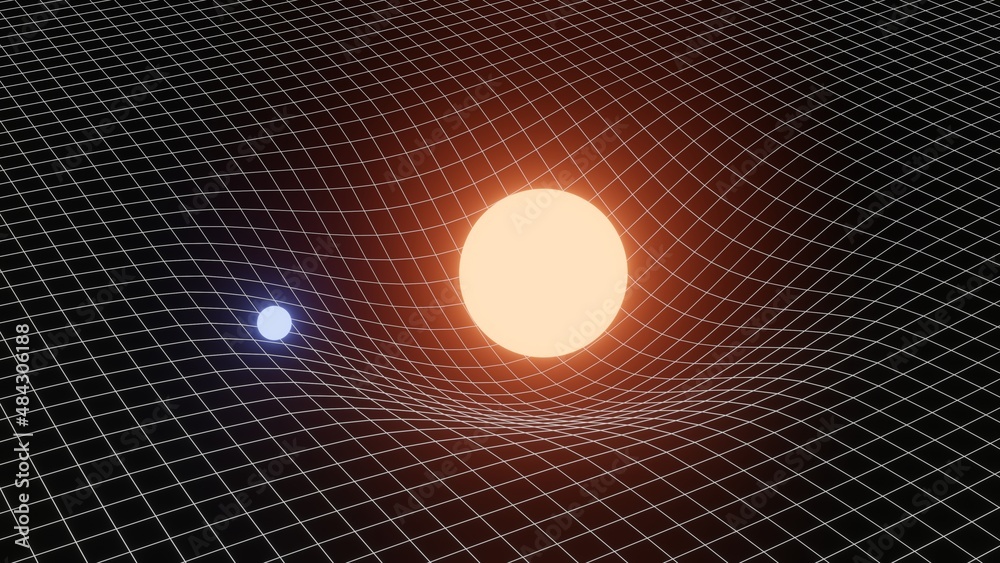

Einstein publishes his theory of Special Relativity, one of the cornerstones of modern cosmology.

E=mc2 is one of the world’s most powerful equations because it says matter can be converted to energy. It makes possible our theories of the early universe.

1907-1915: Albert Einstein

Einstein publishes his theory of General Relativity, which describes gravity.

He paves the way for the development of modern cosmology.

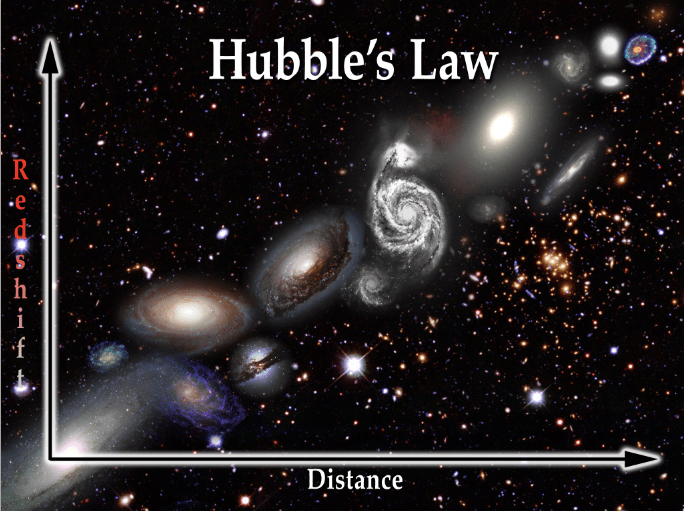

1910: Vesto Slipher

Lowell Observatory astronomer Vesto Slipher measures the recessional velocities of spiral nebulae — that is, how fast they appear to be receding from our earthly vantage point.

1912: Henrietta Leavitt

By now, variable stars like Goodrich’s Delta Cephei are known as Cepheids. Observing such stars, Leavitt discovers a direct relationship between the star’s periodic change in brightness and its luminosity.

1916: Albert Einstein

Einstein recognizes that his theory of relativity won’t allow for a static universe. Gravity will force the universe to contract…unless, perhaps, galaxies are flying apart from one another so rapidly that gravity is helpless to do anything?

Neither possibility seems reasonable. So he adds the cosmological constant to his equations: lambda (Λ).

1918-1924: Annie Jump Cannon

Cannon’s work narrowing spectral classes of stars to the contemporary O, B, A, F, G, K, M and dividing each class into the steps 0-9 is published in 9 volumes under Henry Draper’s name.

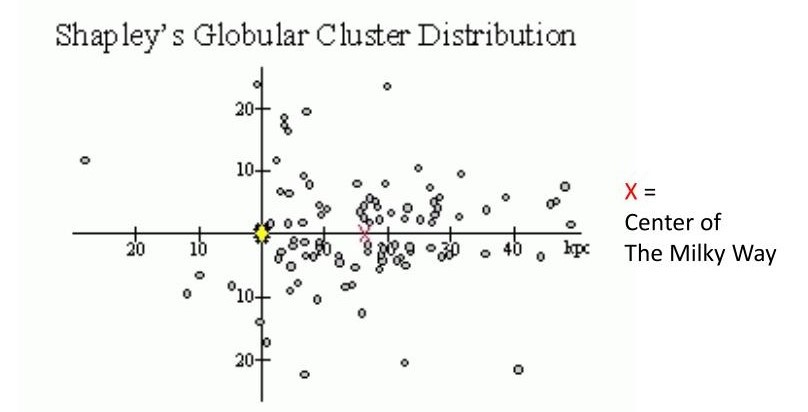

1920: Harlow Shapley

Shapely uses Cepheid variable stars in globular clusters as a distance indicator to measure the size of “star system.”

He doesn’t realize there are multiple types of Cepheids, or that some of them appear fainter than expected due to extinction from interstellar dust clouds. His estimate of the size of the galaxy, 30 kiloparsecs (kP), is 3 times the modern estimate of 8.5 kiloparsecs.

However, he is able to show that the sun is not the center of the star system…and reveals that the star system is bigger than the Herschels had thought.

Although Leavitt’s work is critical to Shapley’s success, he doesn’t give her appropriate credit.

(Anyone wondering what the heck a globular cluster is? I’ve teased them for years…and a couple posts from now, we will finally explore them!)

April 26, 1920: Great Debate

The stage is set for the greatest expansion yet of humanity’s view of the universe.

Lick Observatory astronomer Heber Curtis takes Parsons’ position: spiral nebulae are “island universes.”

Harlow Shapley argues that the spiral nebulae are swirls of gas and faint stars within our own star system.

Both present their arguments at the National Academy of Sciences. But there just isn’t enough evidence to rule anything out.

1924: Edwin Hubble

Mount Wilson astronomer Edwin Hubble uses the new 100-inch telescope to resolve the Great Debate.

His observations of Cepheids in the Andromeda Galaxy — still called the Andromeda Nebula at the time — reveal that those Cepheids must be very distant, outside the Milky Way star system.

1925: Cecilia Payne

Payne completes her PhD thesis studying the compositions of stars — and, indeed, the universe as a whole.

She discovers that the most abundant element in the universe is hydrogen, with helium as a close second and only trace amounts of heavier elements, known in astronomy jargon today as “metals.”

1920s: “Galaxy”

I haven’t found concrete information on when the term “galaxy” entered common usage rather than “star system” or “spiral nebulae.” But it has existed in English since Chaucer’s time, in the 1300s.

Presumably, once the Great Debate was settled, we needed a new term to refer to the objects we had previously called “spiral nebulae.” But I’m honestly not sure when we started calling things “galaxies.”

1929: Expansion and the “Fudge Factor”

Edwin Hubble establishes a linear relationship between Slipher’s “nebulae” velocities and distances to the galaxies measured by Hubble himself.

This relationship becomes known as the Hubble Law — failing to credit Slipher’s half of the work.

The Hubble Law is groundbreaking evidence that the universe is expanding. Now that we know it is not, in fact, static, Einstein calls the cosmological constant “fudge factor” the greatest blunder of his career.

Still, general relativity predicts that gravity should slow the expansion. Astronomers will spend the next few decades trying to make accurate redshift measurements to confirm this.

1938: Lise Meitner

Despite years of being barred from proper lab facilities due to being an Austrian Jew (and a woman), Meitner discovers nuclear fisson.

1948: George Gamow

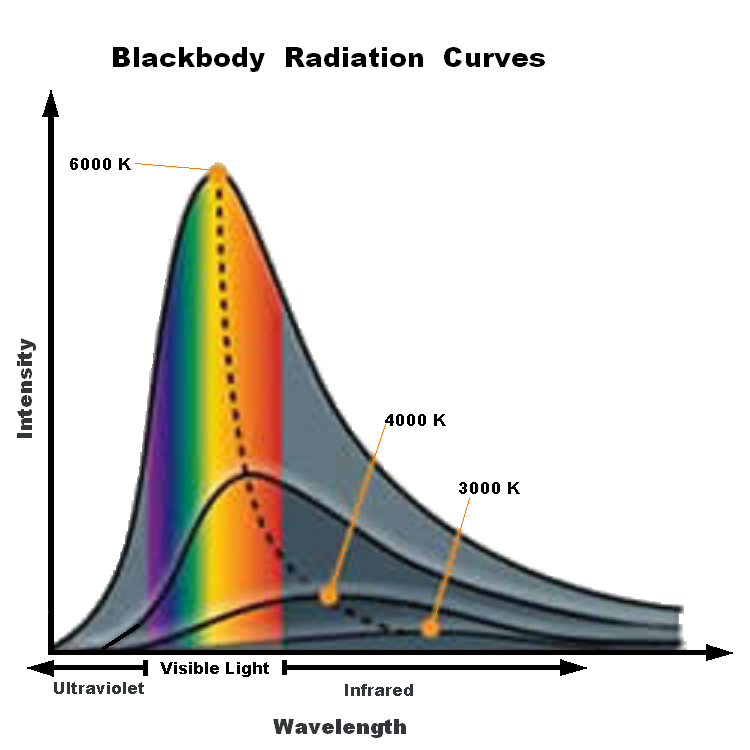

Gamow predicts that right after the Big Bang, the gases in the universe would have been quite hot — plenty hot enough to emit strong blackbody radiation, without any help from nearby stars.

1949: Ralph Alpher and Robert Herman

Alpher and Herman note that if something from that early universe emitted its own radiation, the radiation would be redshifted quite a bit by the time it reached instruments on Earth.

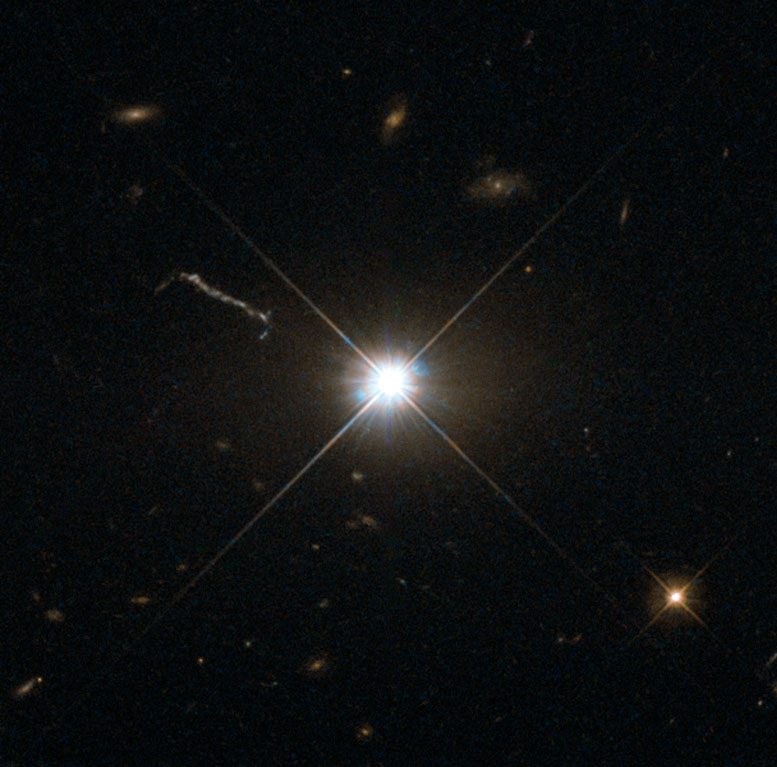

1950s: Quasars Discovered

Radio astronomers stumble over strange star-like objects that they dub “quasi-stellar objects,” which is soon shortened to the term quasar.

1960s: Electroweak Force

Two of the four fundamental forces of nature — the electromagnetic force and the weak force — are found to operate as different aspects of a single force in extremely high-energy processes. The unifying force is termed the electroweak force.

1960s: Star Trek Airs

Star Trek — and other science fiction, both media and literary — is an expression of humanity’s fascination with the cosmos and our place in the universe.

In particular, the Season 1 Star Trek: The Original Series episode “The Galileo Seven” shows our curiosity about the scientific questions at the time: the episode has Captain Kirk and crew explore a quasar.

The episode is woefully inaccurate, but no one could have known that at the time — quasars were a cosmic mystery!

1963: Quasar 3C 273

Astronomer Maarten Schmidt at Hale Observatories discovers that quasar 3C 273 has a redshift of 15.8%. By the Hubble Law, that places it at 749 megaparsecs (2.4 billion light-years) from Earth.

The object is determined to be the active nucleus of a distant galaxy, powered by an erupting supermassive black hole.

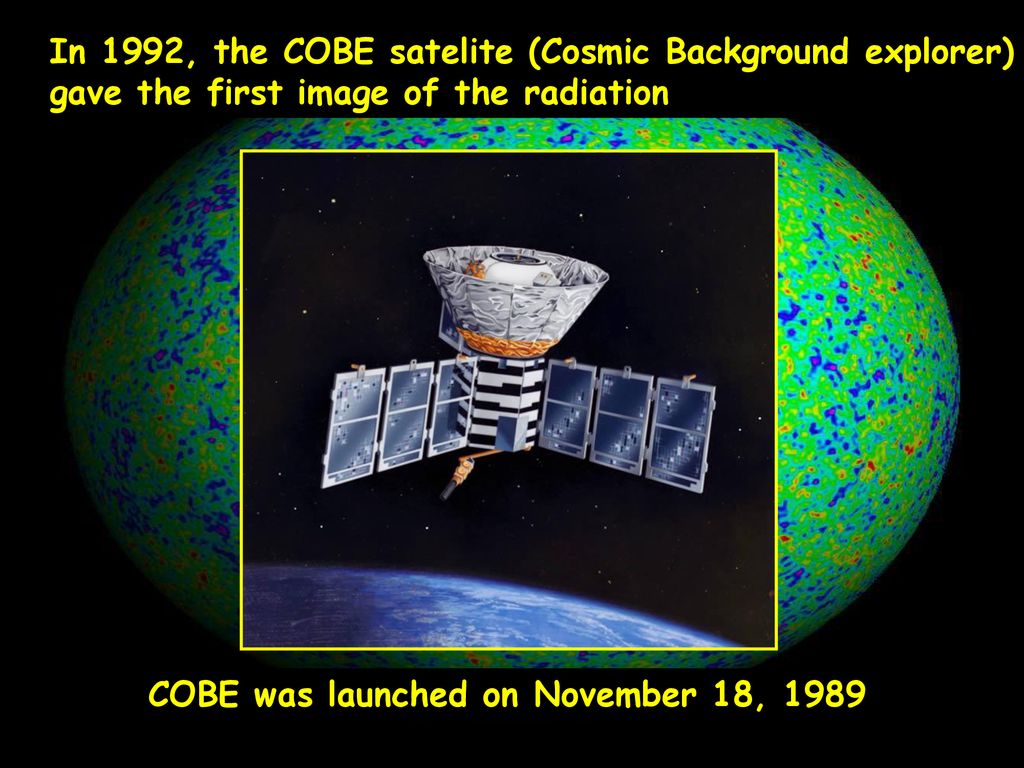

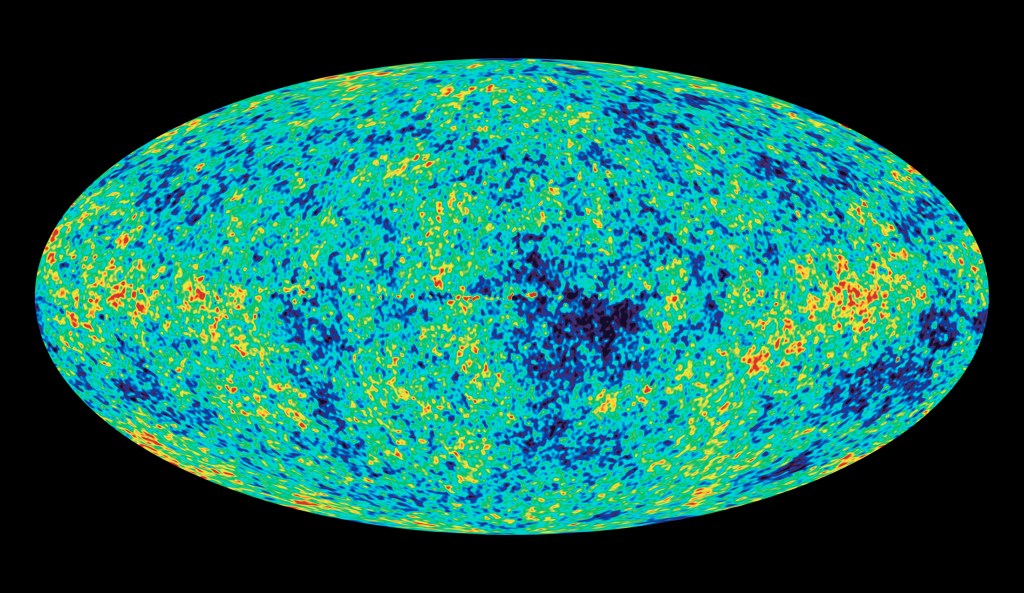

Mid-1960s: Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson

Penzias and Wilson notice a strange background radio signal coming from all over the sky. At first, they attribute it to pigeon droppings in their radio receiver, but after cleaning out the droppings, the signal remains.

They realize that they are detecting radiation from the early universe. It is termed the cosmic microwave background radiation.

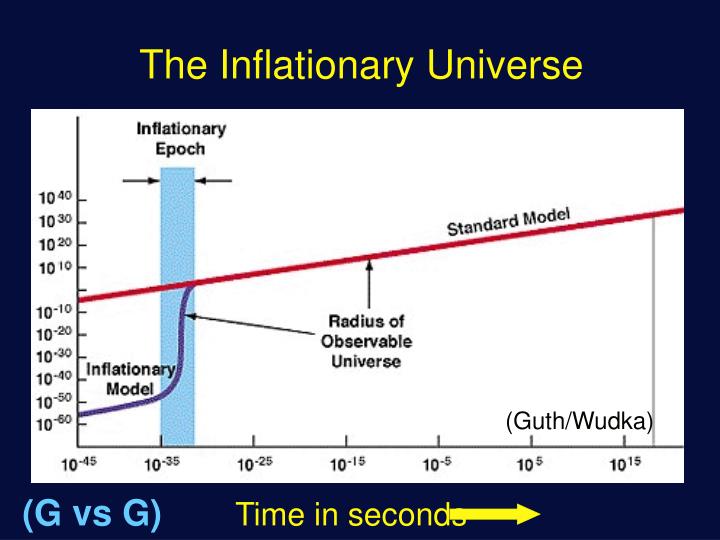

1980: Inflationary Universe

The Big Bang theory is widely accepted, but it still has two problems: the “flatness problem” and the “horizon problem.”

The hypothesis for the inflationary universe solves both of these problems in one fell swoop.

This hypothesis describes a moment in the first microseconds of time when the universe inflated by a factor of at least 1050.

1990: CMB Confirmed

According to theory, the CMB is strongest in infrared wavelengths…which gets absorbed by the Earth’s atmosphere and never reaches ground instruments.

In 1990, the launch of space telescopes enables astronomers to finally confirm the theory.

They discover a perfect blackbody curve that closely matches the predicted temperature, confirming the result.

1990: Hubble Space Telescope

The launch of the Hubble Space Telescope changes everything for cosmology.

Since 1929, astronomers have attempted to measure a slowing of the universe’s expansion. Now, with the Hubble Telescope at their disposal, two competing research teams calibrate type 1a supernovae as distance indicators.

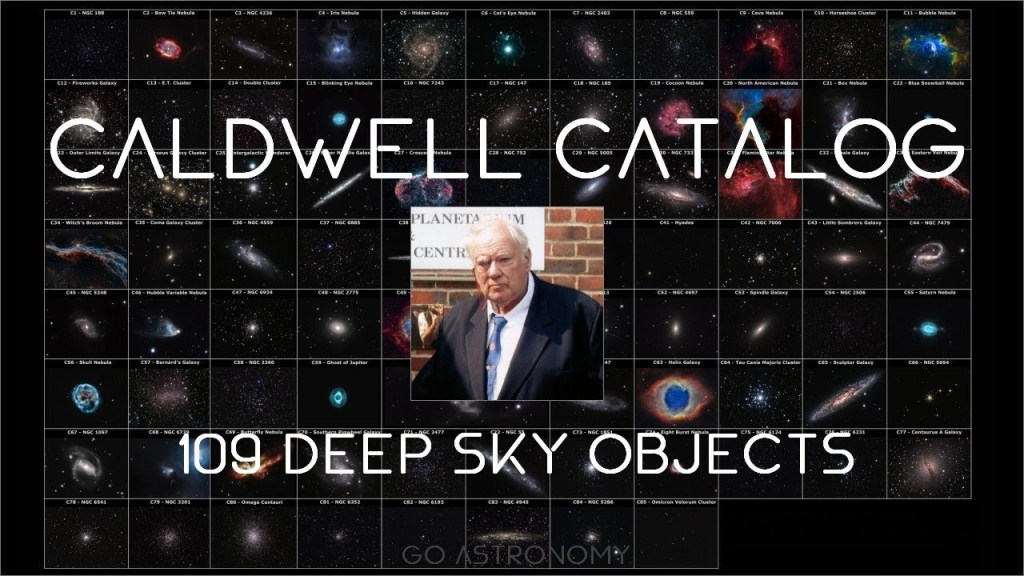

1995: Patrick Moore

Patrick Moore compiles his answer to the Messier Catalog. The Messier catalog was never intended to be a comprehensive catalog of deep-sky objects; most objects could be mistaken for comets (using Messier’s 18th-century equipment) and are visible from Paris, France.

Moore’s catalog is similarly-sized — 109 objects compared to Messier’s 110 — and consists of proper deep-sky objects visible from both hemispheres.

To avoid confusion, because both Moore and Messier begin with the same letter, Moore uses his second surname of Caldwell to publish the catalog.

1998: Acceleration

The two research teams using the Hubble Telescope to detect a slowing of the universe’s expansion discover the opposite result: the expansion of the universe is accelerating.

This incredible result requires confirmation.

2009-2013: Planck Space Telescope

The Planck Space Telescope improves upon both COBE and WMAP’s measurements of the CMB, allowing astronomers to make calculations of the universe’s shape (flat, positively curved, or negatively curved).

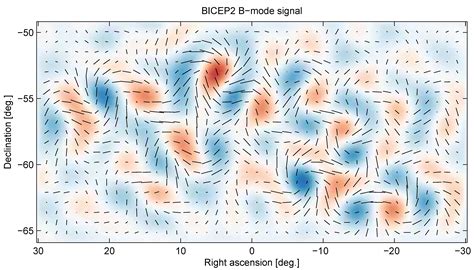

2014: Inflation Confirmed

A worldwide team of researchers finds a polarization signature in the CMB that matches that predicted by inflation.

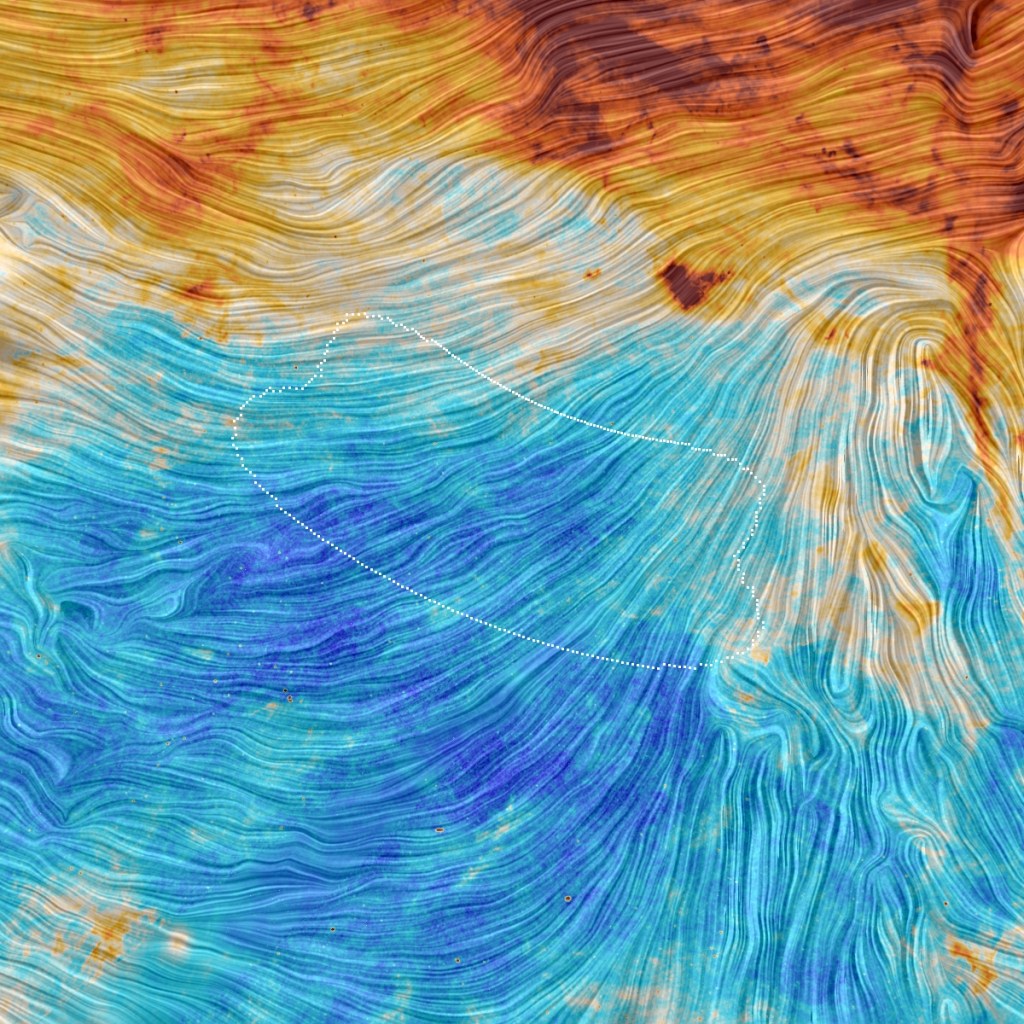

2015: Inflation…Not Confirmed

Upon further investigation, the CMB polarization signature is discovered to be a result of interstellar dust, not inflation.

But hey, it’s all part of the process! Inflation is still the leading hypothesis. We just don’t have dramatic confirmation of its accuracy anymore.

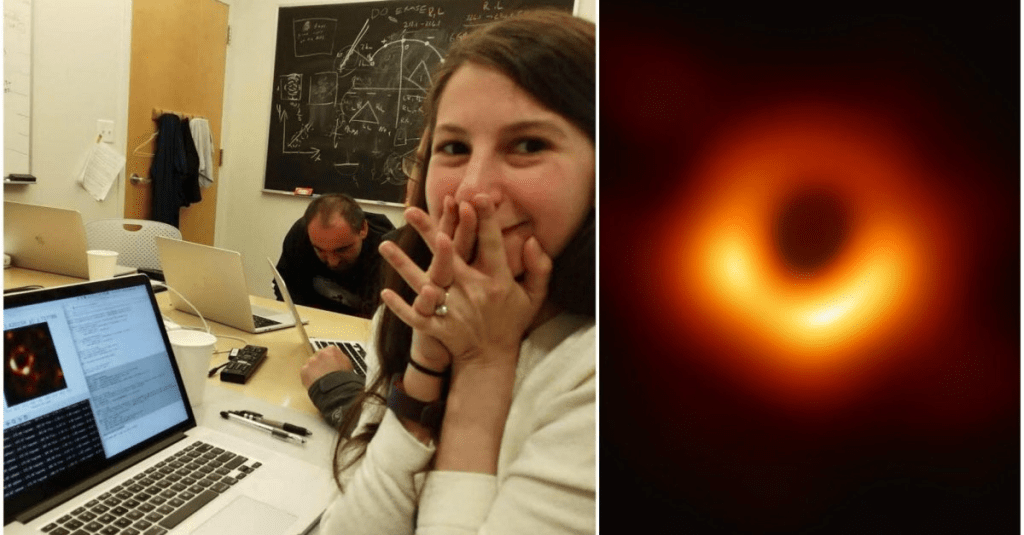

April 10, 2019: First Photo of a Black Hole

Using an interferometer nearly the size of the Earth — the Event Horizon Telescope — Harvard professor Dr. Katie Bouman and a worldwide team of scientists image the halo of gas surrounding a black hole for the first time.

The target is the supermassive black hole at the heart of M87, the largest known elliptical galaxy.

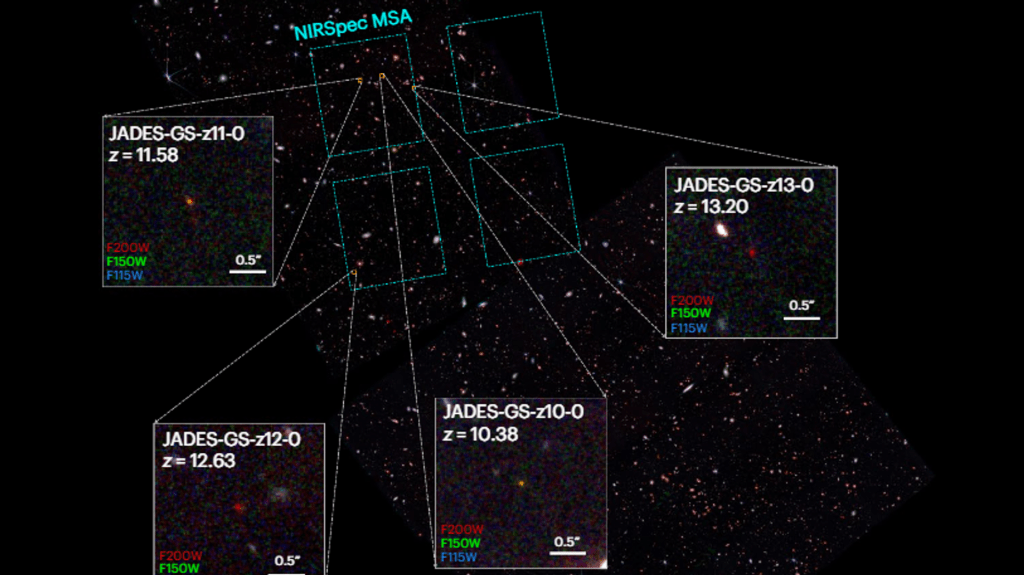

2022: JWST Raises Questions

JWST detects galaxies far more distant (and therefore far older) than any seen before…and they appear brighter than the “standard model” of cosmology predicts.

Popular science articles sensationalize this news as a “crisis” among scientists. The opposite is true: it’s an opportunity for discovery.

It’s exciting.

2023: Computer Simulations Shed Light

Computer simulations answer some questions about JWST’s early galaxies: their brightness does not necessarily disagree with the standard model.

Still, there are discrepancies in cosmological measurements, and it is JWST’s very mission to shed light on those questions.

Science is a process, not an answer. It is a process of discovery. There’s so much we still don’t understand, and that’s okay — that’s part of the fun!

As Star Trek puts it, space is the final frontier — and an astronomer’s job is to boldly go where no one has gone before.

I often hear that people find the study of the universe humbling. That it reminds us of how small we are in the grand scheme of the cosmos.

But in the little blip of cosmic time that we’ve been alive on the little blue mote of dust we inhabit, look how much we’ve accomplished.

I find that inspiring.

We humans aren’t perfect, and we’re definitely small compared to the cosmos. But we should be proud of all we’ve discovered and learned. I think the story of human discovery is pretty dang impressive!

Next up, we’ll revisit the elusive dark matter — this time, exploring what we don’t know about it.

Leave a reply to disperser Cancel reply